NHRA SAT BACK TO SEE WHAT WORKED, AND WHAT DIDN'T

Sometimes the best measure is to let others take risks and then sit back to determine what works and what doesn't. This practice is the luxury NHRA had back through the years when it had competition in the drag racing sanctioning body world. The fringe series, American Hot Rod Association [AHRA] and International Hot Rod Association [IHRA], always daring to be different, created programs and procedures that often found their way into the NHRA's formula.

"The NHRA did the smart thing," confirmed noted drag racing historian Bret Kepner. "They let the IHRA or the AHRA start these weird things, and they sat back and watched to see if it worked. And if it worked, they used it, and if it didn't work, they didn't use it."

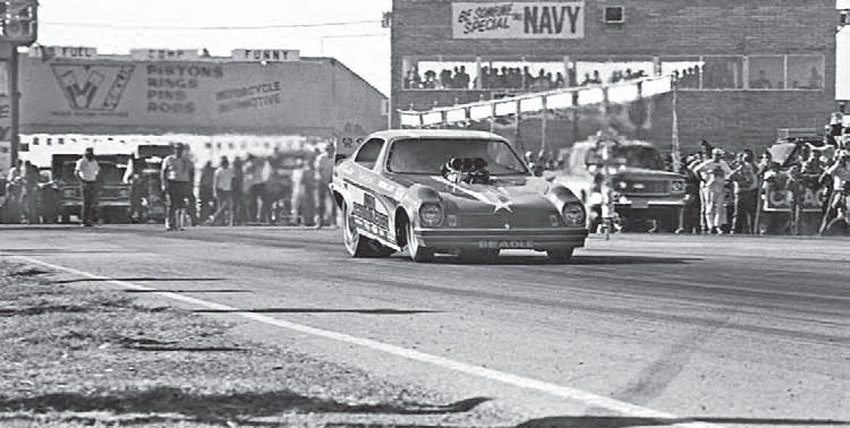

For instance, the AHRA was one of the first to develop set qualifying sessions for their classifications, a move quickly adopted by the IHRA, which first came on the scene in 1971. AHRA started to implement night qualifying sessions as early as 1966.

For AHRA race fans, if they didn't want to spend all day at the race track, they could show up at 6 PM and catch some of the sportsman drag racing action, but from 7:00 PM until 11, it was non stop professional qualifying on a open format where a team could make as many runs in an allotted period.

For AHRA race fans, if they didn't want to spend all day at the race track, they could show up at 6 PM and catch some of the sportsman drag racing action, but from 7:00 PM until 11, it was non stop professional qualifying on a open format where a team could make as many runs in an allotted period.

AHRA had a procedure to ensure the fans weren't cheated by the one-and-done racers, who would make a run good enough to get in the field and park.

"Each AHRA race has a designated purse for each class but, if a team ignored the Saturday night session, that team was docked a percentage of their prize winnings,” Kepner said. “It became mandatory to run the special Saturday night session.”

In those days, NHRA used a rotational method for qualifying, which would start as early as 7:00 AM, and go all day long, sometimes with racers afforded as many qualifying attempts as they could muster.

For instance, Top Fuel could have been in lane one, Funny car in lane two, etc.

"All they did was take X number of cars out of each lane, and they take three pairs of Top Fuelers, three pairs of Funny Cars, four pairs of Pro Stockers, six pairs of Comp cars, ten pairs of Super Stockers, ten pairs of Stockers, then go back to the beginning of the rotation and repeat," Kepner explained.

So if you saw a photo of Stockers qualifying before a packed house back in the day, it wasn't necessarily because the fans were so obsessed with any form of drag racing. Most of the fans knew that 15 minutes later, the nitro cars would be coming back around. There was only a scant few minutes for fans to head to the concessions or the restrooms before the ‘big cars’ ran again.

One of the plusses for racers under this format was racers could get as many attempts as they wanted [usually a max of six] or as few without their lack of participation noted.

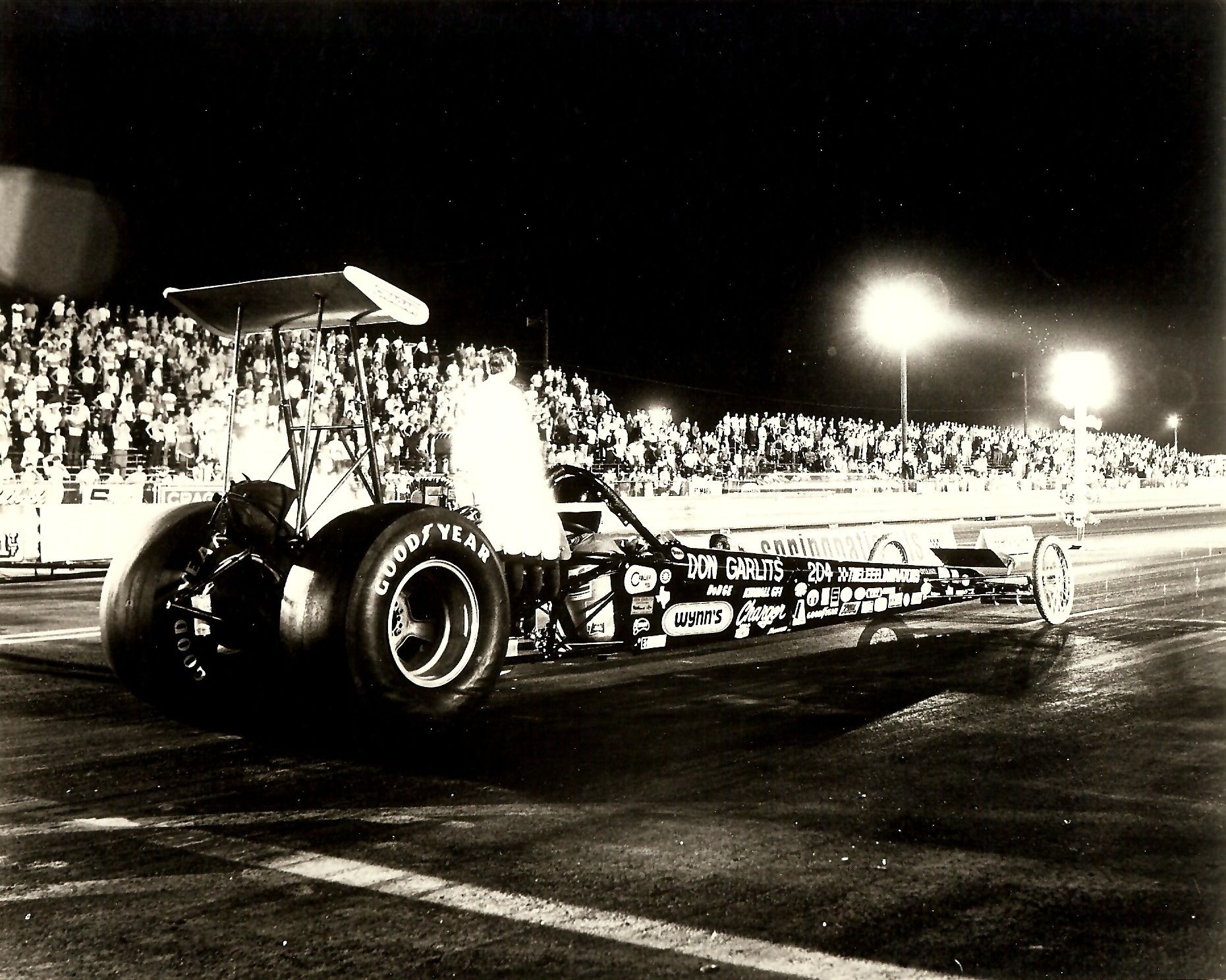

"Most people, unless they were out of the field and weren't qualified, the lower echelon cars would come out as many times as they could," Kepner explained. "After class eliminations ended in 1967, there was no need to make five runs five times in a day to win the class. Using Garlits as an example, he'd go out and make an initial run and go 6.50 and be number one qualifier. Then, somebody else might come out and go 6.49, or a 6.48, and he'd know in his head that he was third. If he wasn't happy with third, he'd go out and make another run. If he was happy with third, he'd stay in the trailer."

"Most people, unless they were out of the field and weren't qualified, the lower echelon cars would come out as many times as they could," Kepner explained. "After class eliminations ended in 1967, there was no need to make five runs five times in a day to win the class. Using Garlits as an example, he'd go out and make an initial run and go 6.50 and be number one qualifier. Then, somebody else might come out and go 6.49, or a 6.48, and he'd know in his head that he was third. If he wasn't happy with third, he'd go out and make another run. If he was happy with third, he'd stay in the trailer."

In those formative days, the primary objective for running the national events was to gain media (magazine) exposure for help get match race bookings through which more professionals made their living. Some of the big names were paid upward of $1,000 per event even more than a half-century ago.

Even though national events weren't profit centers for the racers like the match race scene, winning was more prestigious and certainly more competitive, which led to the next innovation brought forward by the AHRA. Although the Chrondek Christmas Tree starting system was officially introduced in National Event competition at the NHRA U.S. Nationals at Indianapolis on August 29, 1963, many strips utilized electric starting signals, including modified city stop lights, as early as 1950. What AHRA did was revise the Christmas tree for professional and sportsman racing.

From 1963 through 1967, the AHRA used a full five-amber light Christmas Tree just like the NHRA to start its professional and sportsman categories. However, the issue with that system was a 2.5-second countdown which resulted in many foul starts. Always acutely aware of the entertainment aspect of his races, AHRA President Jim Tice knew no fan enjoyed seeing a redlight start and the usually subsequent aborted elimination run. Therefore, Tice instituted a simple shortened ‘Tree with used a single amber light followed four tenths of a second later by a green light. The system, in use at tracks like Lions Drag Strip in Long Beach, California, since 1958, made redlighting almost impossible. The new “short Tree” was used in every class at AHRA.

The NHRA did not use a ‘single amber system’ until it debuted as an experiment at the non-points Supernationals at Ontario, CA, in November, 1970. NHRA used a five-tenths of a second delay between the single amber light and the green bulb and only offered what they referred to as a “Pro Start” Christmas Tree in the professional eliminators. The NHRA made standard the “new idea” until the end of the 1971 season when Don Garlits went red at the 1971 NHRA Finals in Amarillo, Texas, and vowed never to return until the four-tenths pro tree was adopted "like the AHRA had." Finally, in late 1972, NHRA made the switch. Interestingly, the NHRA kept its five-amber countdown “Full Tree” in use until January, 1986.

This move wasn't the first time NHRA had followed AHRA's lead in procedure.

The idea of a true points championship, (as opposed to using one “World Finals” race to determine a champion), was initiated by the NHRA in 1960 and was commonplace in at local drag strips since 1950. However, from 1960 through 1964, the NHRA’s program crowned only two points winners, (one for the “hot cars” and one for “production cars”). The first attempt at a program which crown individual winners in each eliminator category came when Tice launched the Grand American Series of Professional Drag Racing in January, 1970. The ten-race series offered points in every category and, for the first time, paid a surprisingly stout season-ending payout to the top ten finishers in each. As he did by paying the sport’s biggest Top Fuel and Funny Car racers to attend the entire series, Tice attempted to use the structure and lucrative nature of the new series to entice the pioneers of Pro Stock to commit exclusively to AHRA.

At the time, NHRA's Wally Parks had no interest in fielding a heads-up Super Stock class.

In a Motor Trend article, Parks said, "This heads up gas funny car class is becoming popular is so out of touch with what is actually produced. There's no way in the world we're ever going to do anything like that. We have a great product. We're going to concentrate on that."

Tice took advantage of the situation and made a run for those drivers Parks didn't want to make professionals.

The United Drag Racers Association [UDRA] had made the heads-up Super Stockers a professional division in 1967, and AHRA followed suit in 1968. Even NASCAR [drag racing] had a version of the heads-up Super Stockers called Ultra Stock. Had Tice not made a substantial bid for the marquee drivers of the day such as Ronnie Sox, Dick Landy, Don Nicholson, and Bill Jenkins, the NHRA likely would not have adopted the heads-up Super Stock format which they would debut as “Pro Stock” in 1970.

At the 1969 NHRA U.S. Nationals, the aforementioned drivers, who had been offered cash for AHRA exclusivity, essentially pointed out that unless there was a professional heads-up class in NHRA, they would commit to AHRA.

By October 1969, NHRA announced its Pro Stock division cars of 1968 or later American production cars, with a minimum of 7 lbs. per cubic inch and weighing 2700 lbs. or more.

In 1966, while NHRA classified the Funny Cars as Fuel Dragsters and ran them in the new Super Eliminator with handicap starts, the AHRA was conducting its first official heads-up up category for match race Stockers at its Winter Nationals at Irwindale, CA. Although the UDRA actually held the first National Event titles in 1965 for what would become known as ‘Funny Cars’, the AHRA put the new machines on the same level as the venerable Top Fuel Dragsters for three full seasons before the NHRA ever moved beyond a handful of special races for the breed.

The IHRA spawned out of the AHRA when its series founder Larry Carrier had gotten sideways with Parks and then Tice leaving him with no other choice than to do his own deal. When the IHRA hit the track in 1971, a lot of what AHRA had done in the sportsman ranks was implemented into the new series, namely the Formula Stock classes, which essentially found a place for any sportsman racer to compete.

RELATED STORY - LARRY CARRIER: DRAG RACING'S REBEL

Not many moves were made until the end of 1976 when the IHRA scrapped the traditional Pro Stock pounds per cubic inch format used universally across the board. IHRA established an unlimited displacement format at 2350 pounds and set the stage for what would be the future of the class. AHRA followed in 1981 by allowing its racers either unlimited cubic inch engines at 2350 or small block engines on nitrous oxide at 2200. At the end of the 1981 season, with the IHRA's Pro Stockers stealing the headlines with seven-second runs, the NHRA scrapped its cumbersome factory hot rod format for the 500-inch platform. For the first time since 1977, IHRA-only cars found their way over to NHRA events and vice versa.

Not many moves were made until the end of 1976 when the IHRA scrapped the traditional Pro Stock pounds per cubic inch format used universally across the board. IHRA established an unlimited displacement format at 2350 pounds and set the stage for what would be the future of the class. AHRA followed in 1981 by allowing its racers either unlimited cubic inch engines at 2350 or small block engines on nitrous oxide at 2200. At the end of the 1981 season, with the IHRA's Pro Stockers stealing the headlines with seven-second runs, the NHRA scrapped its cumbersome factory hot rod format for the 500-inch platform. For the first time since 1977, IHRA-only cars found their way over to NHRA events and vice versa.

Pro Comp, today's Top Alcohol in a combined eliminator, started to wane in participation. The IHRA, which was then primarily based in the southeastern U.S., found themselves in barren regions as far as these cars were concerned. The NHRA started to feel the same thing except in the West and northeastern regions where it flourished.

At the end of the 1976 season, Tice let it be known he planned to drop Pro Comp.

"Tice said, 'We're dropping the class," Kepner said.

Then the floodgates opened.

"Tice added, 'As soon as I said we were dropping the class, we got phone calls from more people than ever ran with us in the class," Kepner recalled. "So he brought it back in 1977 but he split it. He put the injected fuel and blown alcohol Dragsters and Altereds in one qualified eight-car field named Pro Comp Dragster and the injected fuel and blown alcohol Funny Cars in another eight-car field. Each ran for their own World Championship.

The IHRA dropped Pro Comp in 1980, and NHRA followed the AHRA's lead with the split class.

IHRA didn't miss Pro Comp one bit as in 1978, they borrowed the AHRA's Top Comp format to create their quick 32 Pro Street bracket category, and unlike the AHRA's program, which was essentially Jr. Fuelers bracket racing at an elapsed time which was quicker than Pro Stock, the IHRA's version was doorslammer centric.

The IHRA's Pro Street division evolved into what would become Top Sportsman, which spun off a professional division with Pro Modified and eventually an open-bodied version with Top Dragster.

Pro Modified joined the NHRA in 2001 as an exhibition division, and after IHRA ceased to remain a viable race series, the NHRA picked up both Top Sportsman and Top Dragster.

Maybe the NHRA wasn't intended to be the leader in drag racing innovation, considering the sanctioning body wasn't created for drag racing.

"The NHRA wasn't created for drag racing," Kepner explained. "In 1951, Wally Parks wanted to unionize the car clubs across the country. He wanted to create one big federation instead of all these splintered groups considering every town had ten different car clubs. Some had eight members, while others had 15. Every town had multiple car clubs. And when a bunch of car clubs unionized or consolidated in a specific town, they created what was called a timing association.

" Wally, of course, was president of the Southern California Timing Association in 1937. So when the street racing problem got big enough to attract attention and hot rods were getting a bad name, Wally and his close friend Robert Peterson saw a huge market because the nation was full of 18- to-24 year-old males. The success of Peterson's new magazine, named ‘Hot Rod’, which started in 1948, proved the huge market for consolidating these guys into one big national federation.

"The only reason the NHRA got into drag racing in 1953 was that between 1951 and 1953 was, all the car clubs got into drag racing."

And in the end, NHRA won the war against the AHRA and later IHRA because it was perfectly fine to sit back and see what worked and what didn't.