DRAG RACER WHO WENT BLIND RACES HIS WAY INTO GUINNESS WORLD RECORD

Dan Parker once described himself by saying, “I’m not a blind man trying to race, I’m a racer who went blind.”

Dan Parker once described himself by saying, “I’m not a blind man trying to race, I’m a racer who went blind.”

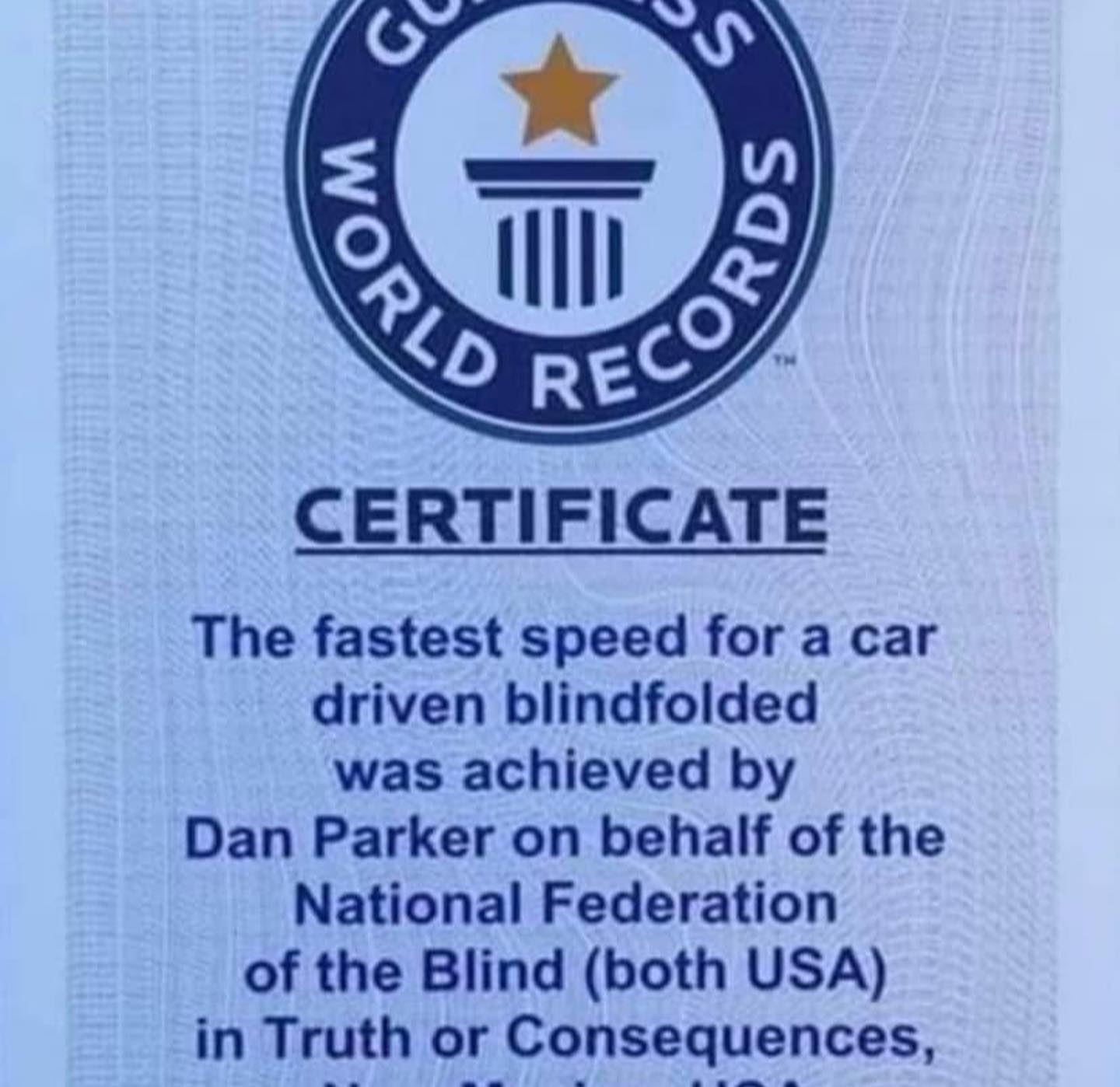

Now, he’s a blind racer who’s earned a place in the Guinness World Records. Last Thursday, Parker became the fastest blind racer of all time. His two-run average of 211 mph at Spaceport America on March 31, 2022, came 10 years to the day from when he lost his sight in a Pro Mod crash. It broke the mark of 200.9 mph set in 2014 by England’s Mike Newman, who was born blind.

Parker’s record-setting blast down the runway outside Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, came two years after he fell short due to performance issues and high winds.

Not surprisingly – at least to Parker – there wasn’t much of a celebration of his achievement … not yet, anyway.

“I put a post up on Facebook that I feel like a boxer that just went 12 rounds because I can finally put my gloves down. I’ve been fighting for this record for almost five years, and the fight’s over,” said Parker, who lives in Columbus, Georgia.

“You’re a racer, and when the race is over, you just get in the truck and come home. … I’ve always considered myself a humble person, so it really hasn’t quite set in with me. I know that what we just did was major, but it’s hard to understand how to celebrate it because as a racer you just move on to the next race. It’s weird.”

This year’s attempt at the record, like 2020, had more than its share of late-stage challenges to overcome.

“The whole time before, I was running a stock 6L80 transmission, which is finicky to say the least,” Parker said. “I was so fearful that it would fail that I made the decision roughly six weeks ago to install a Turbo 400 in it. I contacted Jeremy Jones at RPM Transmission, and he pulled the strings to make it happen.”

Team members Jeff Pope and Clyde Carlson made the night-long drive to pick up the transmission. Parker’s nickname for them is Fish ‘n’ Chips, as their ride to Indiana was a 1987 Mercedes that Pope converted to run on recycled vegetable oil. They returned to Georgia with the transmission on March 4, and on March 5, the team began installing it, which isn’t as simple a task as it might normally sound for mechanically minded people.

Team members Jeff Pope and Clyde Carlson made the night-long drive to pick up the transmission. Parker’s nickname for them is Fish ‘n’ Chips, as their ride to Indiana was a 1987 Mercedes that Pope converted to run on recycled vegetable oil. They returned to Georgia with the transmission on March 4, and on March 5, the team began installing it, which isn’t as simple a task as it might normally sound for mechanically minded people.

“The transmission is in the back of the car, so I had to cut the trans tunnel to get it to fit, which snowballed into a whole lot of other issues,” Parker said. “We had to leave for New Mexico on March 26, so we had three weeks to get all that together.

“The car also had a new motor in it, too. I knew this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to have the record, and I wanted to have a spare. Last June, I reached out to Tom Vigue at 3V Performance in Denver, North Carolina, because DART didn’t have any blocks, and Tom had one in stock. He said he’d sell it to me without the stipulation that he build the motor, so we worked on that since last June. He was able to dyno it (784 horsepower naturally aspirated) and get it finished just a few weeks before the race. So, a new motor, new transmission, and a bunch of fab work. The guys that have helped me made that happen.”

The Fulton Competition-built 427 Parker had employed in prior attempts was freshened and ready to go if the new powerplant had issues. The 3V Performance engine makes about 75 more horsepower thanks to cylinder heads that have longer valves, which allow for a larger camshaft to help produce more muscle.

The Fulton Competition-built 427 Parker had employed in prior attempts was freshened and ready to go if the new powerplant had issues. The 3V Performance engine makes about 75 more horsepower thanks to cylinder heads that have longer valves, which allow for a larger camshaft to help produce more muscle.

Parker had initially hoped to make his bid for the Guinness record book last November, but the outbreak of COVID-19’s Delta variant was a setback. Spaceport, which is located on 18,000 acres next to the Army’s White Sands Missile Range, was only available for runway rentals Tuesday through Thursdays. Weather conditions in January and February took those months out of the picture, and the only dates available in March were the 29th-31st.

There was also the matter of arranging to have Guinness officials onsite to verify Parker’s performance: “That ain’t easy, and it’s expensive,” Parker said.

Parker, who was ADRL’s Pro Nitrous champion in 2005, is able to drive, and race, using a custom-built guidance correction system developed by a friend, Patrick Johnson. A course is plotted, and as Parker drives, the navigation system provides feedback through a headset that allows him to make corrections and stay close to the map’s centerline.

After coming up short in 2020, Parker decided that one way to increase his chances of success was with more driving practice. To accomplish that, he bought a locally owned C4-model Corvette – a car whose handling characteristics are similar to his C6 ‘Vette racing entry. A second guidance system was built for the C4, and Parker made countless laps going up and down the track at Phenix Drag Strip in Phenix City, Alabama.

“Burned up two sets of brake pads doing it,” he noted.

Parker and volunteers from states as far away as California and New Hampshire convened in New Mexico last week. The chance to make runs Tuesday were wiped out by winds of 40 to 50 mph, and Wednesday morning saw steady winds of 30 to 40. But by late Wednesday, the wind had subsided enough for Parker to make runs of 158 and 176 mph.

Parker and volunteers from states as far away as California and New Hampshire convened in New Mexico last week. The chance to make runs Tuesday were wiped out by winds of 40 to 50 mph, and Wednesday morning saw steady winds of 30 to 40. But by late Wednesday, the wind had subsided enough for Parker to make runs of 158 and 176 mph.

On Thursday, the final day, Parker aborted his first run, which was clocked at 187. The second pass resulted in a 205-mph mark – his first time over 200 – and he knew there was more if one issue could be corrected.

“I could feel it in my seat that there was a pretty good-sized bump somewhere along the run, and the car would wander around a little bit,” he said.

That feedback resulted in a change to the compression in the shock absorbers and some minor tweaking in the steering, and Parker and Jason White saddled up again. Parker called White his “co-pilot,” but he was actually just along for the ride. GoPro cameras were installed in the car to provide video evidence that Parker actually did all the driving. The only assistance he had was the directional guidance he received over his radio headset and conversation with Johnson back at a base station.

“My molded earbuds from Racing Radios are designed to block out any noise. It’s so quiet in that car. I’ve got mufflers designed to be quiet so I can hear my guidance system,” Parker said. “This is the ultimate exercise in concentration, so it’s much harder than anything I’ve done in my life. It’s a lot harder than driving a Pro Mod, I’ll tell you that.”

With those changes in place, Parker was able to reach his goals, running 210 on his next pass and 212 on a back-up run for a record average of 211.

When did he know he had accomplished his task?

“We had just about brought the car to a stop, and when Tim Kelly from the Loring Timing Association said, ‘Take it to the pits, boys,’ I knew we’d done it,” Parker said. “It was probably another 10 seconds before he called out the 212 on the back-up pass. I knew then all we had to do was verify it with Guinness.”

As soon as Parker arrived in the pits, the Guinness officials removed the memory cards from the GoPros. They took them to a trailer to watch the video to ensure the run was made by Parker – and Parker alone.

What’s next for Dan Parker?

As far as motorsports goes, he’s not sure. He and Johnson are planning to embark on a bicycle project for the blind, he said: “From one extreme of speed to the other.”

Most importantly, he said, is that he wants to use his life story as the foundation for a career as a motivational speaker. That would be in addition to the job he created for himself after being blinded, which is making pens that are available at theblindmachinist.com.

“Mike Newman in England, who had the record, said that one of the mistakes he made was he did it in a borrowed car, so when companies wanted him to speak, he didn’t have the car,” Parker said. “I had a lot easier paths offered to me. I’ve been offered cars to use over the years, and I didn’t (use them) for that reason.

“I wanted to do this in my car, plus it was a horrible feeling having to give (Pro Mod car owner) Bill George back his steering wheel because, basically, that was the only thing left of that car. I didn’t want that responsibility of tearing up somebody else’s stuff, so if it all went to crap, it was all my crap that went to crap.”

The bigger story than the record, Parker said, is the positive, never-say-die attitude that allowed him to set it.

“As a person, this story has to be about so much more than that. It has to be about letting blind children, and children with disabilities, know that they can have dreams and goals and go after them. Don’t let doubters dictate your future. I’ve had a whole bunch of doubters since I went blind and started trying to do this stuff,” Parker said.

“The story is about affecting society and changing society’s perception of what’s possible for the blind. If we’re given an accessible world, we can compete with our sighted peers, and that goes so much into the workplace because, sadly, the unemployment rate for the blind is 70% in America and 99% worldwide. If my story can reach some people – between that and my work making the pens – so that we can change society’s opinion, then maybe the next time a blind person applies for a job, they don’t automatically say no. That’s what we want.

“It’s amazing what you can accomplish when you take quitting off the table.”