Originally published 10-30-2008

Drag racing was a far different motorsport back in 1967, when construction concluded on the original quarter-mile

“Supertrack”: a ground up drag strip project funded by a hard-to-believe budget of over $1,000,000. In 1967, drag racing was still struggling to shuck its notorious public image as weekend recreation for ducktailed juvenile delinquents wearing the inevitable black leather jackets and greasy dungarees. Our image crisis wasn’t helped much by the typical quarter-mile, eighth-mile, or fifth-mile dragstrip of that era. A volunteer crew using plywood sheets and two-by-fours, period usually erected timing towers in a single weekend, then brush painted white. “Guardrails” often consisted of stacked hay bales, old tires, chain-link fences or nothing. Paved turn roads and pit areas, permanent restrooms and bleachers, and uniformed strip employees were still considered luxuries, if they were considered at all.

Old-timers can remember that NHRA had reluctantly lifted its 1957-1964 “Fuel Ban” only three years earlier, and did not yet formally recognize Funny Cars as legitimate race cars, with an eliminator category of their own; AA/Fuel Dragsters were still the undisputed Kings of the Sport. Supercharged nitro racing was booming throughout the country, but beyond the big-buck Ford and Chrysler factory team members, most “professional” drag racers still worked real jobs between events. Even in 1967 dollars, purse money was paltry: Top Fuel winner was lucky to pocket $500, gross, for winning three rounds of open competition. A first-round loser usually collected $100, or less. A $1000 first-place prize was considered big bucks. The richest NHRA purse of all, Indy’s Top Fuel package, paid exactly $2000 cash.

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor’s website

PAT FOSTER AT OCIR

So just imagine the surprise and skepticism that greeted the announcement of a million-dollar drag racing complex, designed with built-in provisions for sports cars, go-karts, and motorcycle road racers, to be constructed on prime farmland owned by Southern California’s largest private landlord, the powerful Irvine Company, in the sleepy village of East Irvine. At the time, the semi-rural location seemed ideal: less than a mile away from the Golden State Freeway (I-5) and the San Diego Freeway (I-405), within driving range of both Los Angeles and San Diego, yet far enough from each city to preclude the encroachment of civilization. Or so it must have seemed to Orange County International Raceway promoters including, Bill White, a member of the Irvine family; Larry Vaughan, whose father had been foreman of the Irvine Ranch; and Mike Jones, the ambitious, innovative local boy who subleased the dragstrip portion of OCIR operations. Vaughan, who also directed the Academy of Defensive Driving, a driving school used mainly by police departments, on the premises, handled the facility’s leasing for the Irvine Company.

Sports cars and motorcycles, which tried racing around a makeshift road course connecting portions of OCIR’s pits, return road and staging lanes, never attracted much interest, becoming early deletions from the master plan. The hoped-for Grand Prix and/or Indy-car competition reflected in the track’s logo design and “international” billing never materialized. That on-sight restaurant folded early, due to weak weekday business, followed by the evacuation of Johnny’s Speed & Chrome. An innovative underground pit-access tunnel from the spectator parking lot repeatedly caved in, forcing its closure and leaving the strip with an incurable “dip” just ahead of the finish line. Trick roller starters, powered by a Chevy small-block V8, in the hot car staging area fell into disrepair.

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor’s website

FORCE – THE OCIR DAYS COURTESY OF JACKSON BROTHERS

With little or no maintenance, the kiddie’s playground in the pits became the pits, degenerating into a potential safety hazard. Light bulbs that burned out in the elevated electric scoreboard were not always replaced, making the numbers difficult or impossible to decipher. Hungry squirrels attacked sections of the subterranean wiring, creating a troubleshooter’s nightmare. Even the popular Four Preps’ advertising jingle came under fire and was ultimately forced off the air, according to one former front-office staffer, following bitter disputes over royalty payments. Professional feature events were gradually cutback to a monthly schedule, poorly attended Sunday shows were scrubbed, and the weekly sportsman was consistently outdrawn by Lions Drag Strip and Irwindale Raceway, both of which catered to a “little guy” contingent often turned off by OCIR management’s unrelenting emphasis on professionalism.

The strip’s sportsman attitudes improved significantly following the July ’73 departure of whiz kid Jones, but virtually everything else would suffer in his absence. An ever-mischievous Jim Tice, the late president of the American Hot Rod Association, quickly snapped up the expensive dragstrip lease, already in five figures monthly. His first move, naturally, was the termination of OCIR’s long running NHRA sanction. Next, Tice turned the famous Champion Tower into Western headquarters for all AHRA operations, pouring salt into the wound. “We just moved right into Wally Parks’ own backyard,” chuckled Tice at the time, unaware of the true price to be paid for his startling little coup.

C.J. “Pappy” Hart, the successful Santa Ana and Lions manager, was coaxed out of retirement and got the transition off to a fairly smooth start that summer, overseeing the first national event in OCIR history (AHRA Grand American West). Before the ’73 season concluded, however, Hart had resigned after clashing repeatedly with AHRA executives Rick Lynch and Blaine Laux, a man best known as Tice’s personal pilot. Laux, a former Kansas City sportsman racer familiar with neither track management nor the tricky California marketplace, nonetheless was named OCIR’s third strip manager of 1973.

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor’s website

OCIR’S DAY OF FIRE

The best of the best ran at OCIR which first entered the racing world under NHRA sanction then went AHRA and returned to NHRA before closing at the end of 1983.

The subsequent season, handicapped by some of the worst weekend weather in local history, enjoyed some successful promotions, but the box office repeatedly bled red ink. Even the well-attended variety shows starring Evel Knievel, Bo Diddley, and Flash Cadillac failed to recover losses suffered by the AHRA’s second annual Grand American West, which was unfortunately scheduled directly opposite Ontario Motor Speedway’s inaugural California Jam; merely the biggest single-day rock concert in history, attracting 250,000 potential drag fans. Not long after, Tice walked away from AHRA leases at both OCIR and sister track Fremont Raceway, estimating his combined California losses at roughly $1,000,000 in less than a year. Both strip managers stayed on, however, and both tracks retained AHRA sanctions under subsequent tenant Larry Huff, another inexperienced race promoter, who took over June 1, 1974.

An active Pro Stock driver and self-made millionaire, Huff told a Drag News editor that he originally assumed Tice’s OCIR and Fremont leases purely on impulse, reacting to a heated public disagreement with NHRA officials working the ’74 Bakersfield March Meet. Accounts of the incident vary slightly, but Huff admitted to trying to enter his Soapy Sales Dodge Dart with an expired NHRA competition license. Worse, the typewritten “year of issue” had evidently been tampered with to conceal this fact. The high-ranking female official who detected this discrepancy with NHRA records supposedly ripped Larry’s license into several pieces while lecturing him loudly, in front of God and everybody. Less than three months later, Huff was suddenly in the dragstrip business in a big way, operating two major tracks inside NHRA’s home state.

Fortunately, though, business was not so good for Mr. Huff. He abandoned Fremont before the end of that summer, citing irreconcilable differences with the landlord, then dropped OCIR in March ’75. The move surprised most observers, coming on the heels of four winter Funny Car promotions averaging over 10,000 paid spectators each. “In eight months, even though the strip did as well as ever as it’s ever done in its life, we lost like 65 thousand (dollars),” said Huff at the time. “It’s just a very poor business. If we were lucky, (OCIR) could gross a million, million-one a year and break even- and that’s bad business!”

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor’s website

Incredibly, Supertrack subsequently sat idle most weekends while Irvine Company liaison Larry Vaughan, last of the plant’s founding fathers, interviewed wary potential lessees. The only man willing and able to assume OCIR’s league-leading over head tab turned out to be Bill Doner, whose International Raceway Parks organization had previously gobbled up unwanted leases in Seattle, Portland, Fremont, and elsewhere. IRP also controlled OCIR’s only surviving competitor, Irwindale Raceway, and Irwindale manager Steve Evans consequently assumed day-to-day direction of IRP’s three California holdings. OCIR’s sanctioning returned to NHRA, and IRP’s exclusive lock on the SoCal market helped return Supertrack to steady profitability. But the facility was also headed for its most controversial five seasons ever.

Increasingly wilder “Fox Hunt” promotions, well-amplified heavy metal musicians minimal crowd control, jet dragster competition past midnight, and especially a few well-publicized acts of violence generated unprecedented protest from OCIR’s ultraconservative, ever-encroaching neighbors in Orange County. Moreover, it became common knowledge throughout the west that OCIR’s evening features were no place to take the wife and kids. Bracket racers forced to deal with drunks in the pits began arming themselves for Fox Hunt-style meets, or simply staying home. The late-seventies killing of an innocent young racing fan inspired particularly nasty editorials in local newspapers, and is sometimes blamed today for eliminating whatever OCIR support that may still have existed within the Irvine Company.

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor’s website

THE LAST NHRA EVENT AT OCIR

Doner would argue convincingly that OCIR’s super-value acreage has always been doomed to eventual redevelopment into a giant industrial complex, per the landlord’s master plan for the Irvine area, which carries the family name. (The company owned about 68,000 acres of property inside Orange County. The county assessor at more than three billion dollars recently appraised this land.) What nobody could’ve predicted, back in 1967, is the area’s incredible transformation from farmland to congested suburbs inside of a decade. And we all know what happens, later if not sooner, once a rural dragstrip finds itself surrounded by Suburbia. (It should also be noted that this noisy facility was constructed literally within earshot of a major retirement community, Leisure World of El Toro, which already existed in 1967.)

The best evidence of this “inevitable development” theory may be OCIR’s much-improved image since 1980, when Doner, claiming financial losses, closed up shop and moved to Mexico. Riding into East Irvine like the proverbial white knight came Charlie Allen, the ex-Funny Car star whose racing nickname used to be “All-American Boy.” Despite his track management inexperience, Supertrack’s last three-plus seasons turned out to be the smoothest since Jones’ era, and also some of the most profitable ever, according to Allen. Indeed, hardcore drag racing fans returned in droves during the Eighties, often accompanied by wives and kids, for monthly Funny Car features. Allen’s crew, headed by Lynn Rose and veteran SoCal field manager Kenny Green, successfully restored much of the past glory, while dramatically slashing neighborhood complaints. Still, midway through ’82, Irvine Company officials leaked their intentions not to renew the strip’s year-to-year lease.

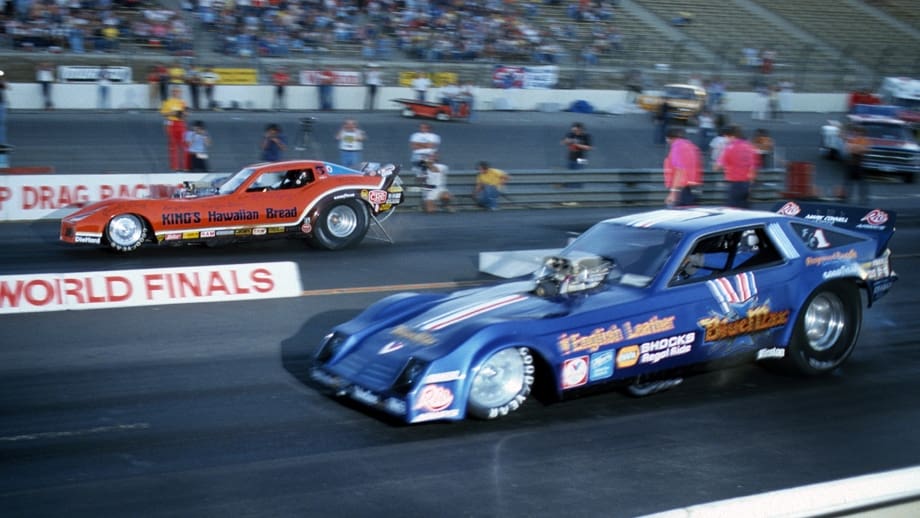

Thousands of signed petitions and Allen’s impressive turnaround probably helped convince the landlord to renew his lease, at the last moment, for 12 months only. What followed was probably the most successful single OCIR season in a decade (including NHRA’s best-attended World Finals ever, and back-to-back 32-Funny car shows on consecutive Saturday evenings.) But this time, the Irvine Company could not be budged; no amount of lobbying would get Allen’s lease renewed. For the record, OCIR went out of business in the wee hours of October 30, 1983.