Drag racing fans once had it better than they probably realized. Three sanctioning bodies spent the 1960s and 1970s clawing for their loyalty, throwing money, perks, and format experiments at racers and spectators in a fight to be king of the hill.

At the top of those three organizations stood equally combustible personalities. NHRA founder Wally Parks ran a non-profit built from car clubs and safety crusades, AHRA boss Jim Tice was a pure businessman chasing opportunities, and IHRA’s Larry Carrier was the wild card no one could control.

Drag racing historian Bret Kepner said the rivalries were so personal that it was almost impossible to describe them collectively. “You almost have to look at it individually,” he said, before boiling Carrier’s attitude toward Parks down to one raw truth: “Carrier absolutely detested Wally.”

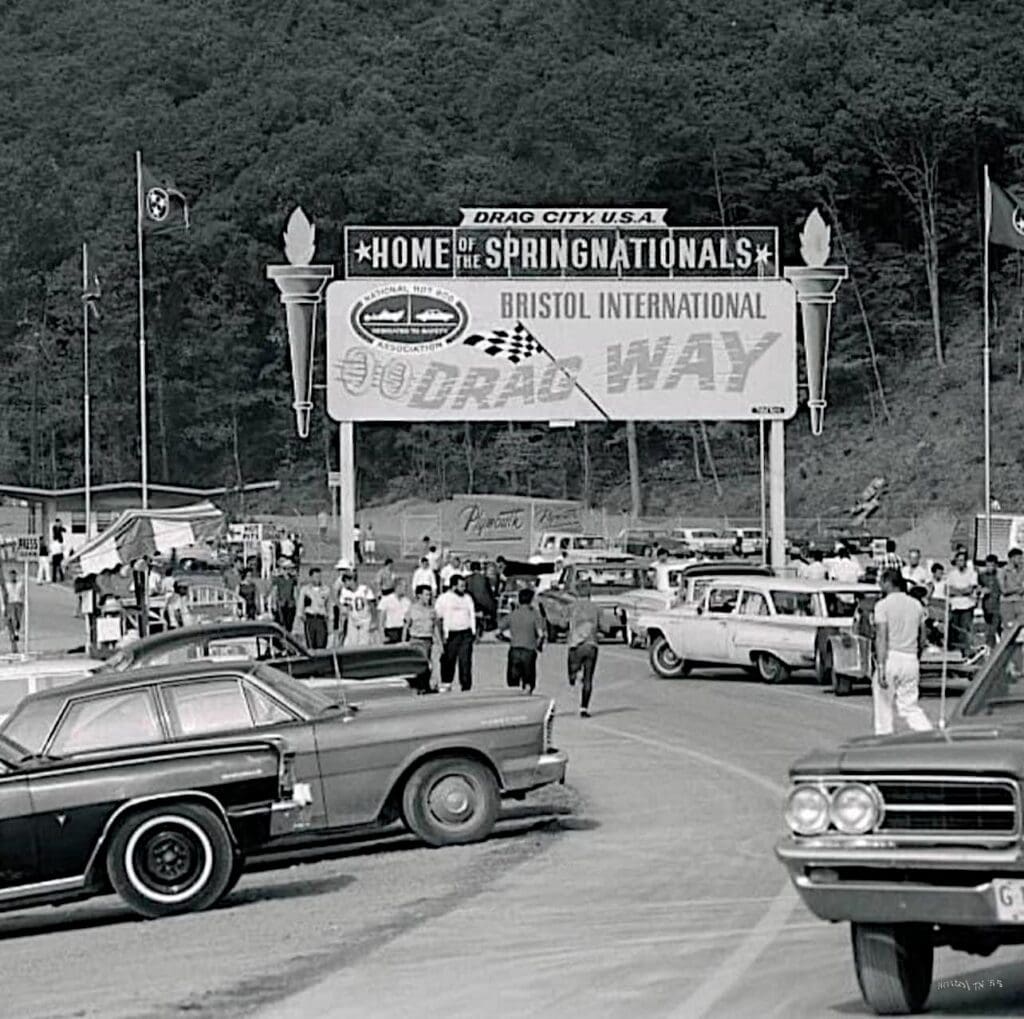

Carrier’s anger came with context. Kepner noted that “the only reason Carrier built that track was for a national event, for an NHRA national event,” and the first race at Bristol almost didn’t happen “over the Funny Car deal.”

Bristol’s Springnationals were supposed to be NHRA’s jewel in the Southeast, a brand-new “super track” that showed the association could operate beyond California and Indianapolis. Then Carrier did what Carrier always did – he pushed.

Kepner said that in 1965, “at the last minute, Carrier told Parks, ‘By the way, I booked in eight funny cars,'” the Match Bash stockers that fans loved and NHRA regarded as a sideshow. Parks protested because “Top Fuel dragsters, they’re our stars of the show,” but Carrier didn’t buy that logic for the Tennessee market.

“And Wally said, ‘Buddy, you’re from California,'” Kepner recalled. “He says, ‘In Tennessee, dragsters are not the stars of the show.'” Carrier believed packed grandstands came from Ronnie Sox, Richard Petty and the Super Stock stars, not front-engine dragsters most locals never saw on Saturday nights.

NHRA reluctantly allowed the cars to run. The Bristol relationship went downhill from there. Former IHRA vice president Ted Jones recalled NHRA events that generated what he called “pitiful“ profit compared to the money Carrier had poured into Thunder Valley.

Jones said Parks demanded major changes to satisfy NHRA’s safety rules, including moving the grandstands back 100 feet from the racing surface. Carrier refused. “Larry said, ‘You’re out of your damn mind. You realize what that would cost?‘“ Jones recalled. “You have any idea what kind of money you’re talking about? And you’re giving this pitiful little check that you’re calling a profit?“

Parks also pushed for a crossover bridge to keep fans out of the staging lanes. According to Jones, Carrier built it, only to be told that without moving the grandstands too, NHRA wouldn’t be back.

That’s when the relationship detonated. Jones remembers Carrier telling Parks, “Good, I don’t need you. There’s got to be another way. There’s got to be a better way that I can make some money with this drag strip and this beautiful facility.“

The insults flew as freely as nitro. Jones said Carrier branded Parks a “California, snaggle-footed, silk-suited son-of-a-b***h“ and ordered him off the property, adding, “Take that tattooed-arm truck driver with you,“ a shot at division director Buster Couch.

Parks fired back at the symbol Carrier loved most – the Bristol tower. “He said, ‘You see that Holiday Inn looking tower, that’ll be a monument to your failure,‘“ Jones recalled. Carrier was so proud of that massive, multi-level structure that Jones said he weaponized it every December.

“Every year at Christmas, Larry would take a picture of the tower,“ Jones said. “He would write on the back of the card, ‘Merry Christmas Wally, the tower is still here,‘ and send him a Christmas card just to aggravate him.“

That feud was only one front in a broader war. Long before IHRA existed, the National Hot Rod Association and American Hot Rod Association were already clashing over control of the sport’s biggest stage at Great Bend, Kan.

Kepner traced AHRA’s origin directly to NHRA’s missteps there, leaving racers and city officials angry over broken expectations and a repaving project the city couldn’t afford.

Out of that mess, Walt Mentzer and frustrated racers couldn’t do AHRA in 1956. Kepner said they signed a five-year deal with Great Bend in three days, working out a loan-repayment plan so the city could repave the bumpy wartime airstrip that passed for a dragstrip.

Parks didn’t take the challenge quietly. A month before AHRA’s first National, Great Bend, NHRA announced its 1956 National, AHRA’s Kansas City, 90 miles away, on the exact same weekend.

“You only got two national events on the same day, 90 miles apart. Are you kidding me?” Kepner said. Big-name racers mostly went to Kansas City, which Keper described as “a disaster,” while AHRA honored its Great Bend contract and stayed through 1960.

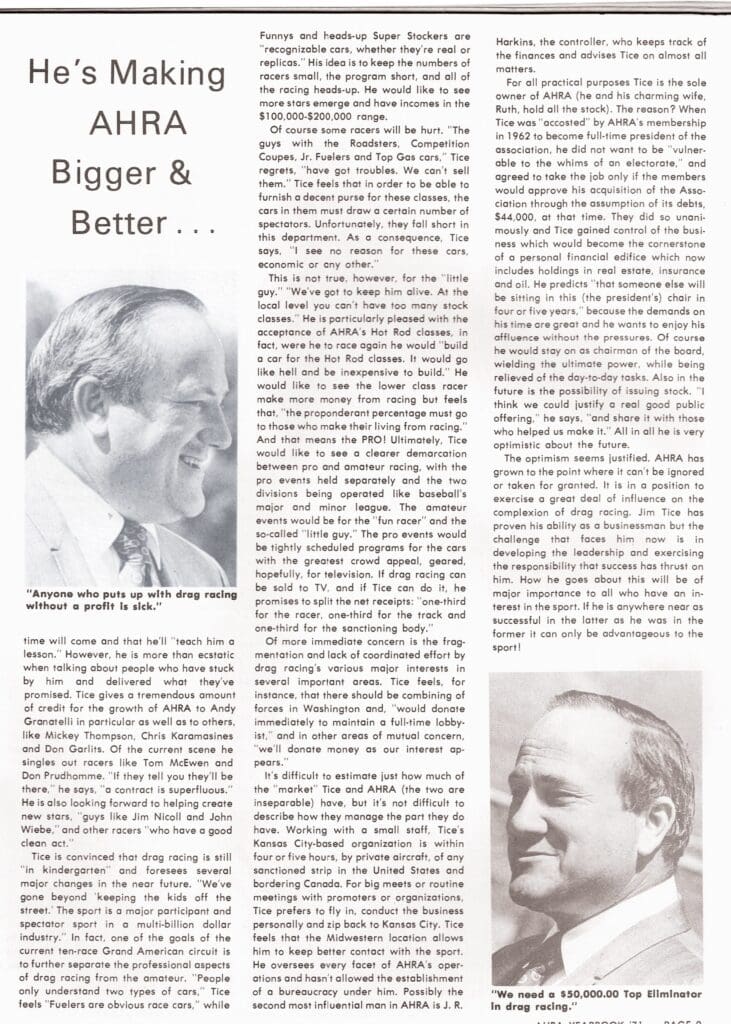

From that point on, the feud between Parks and AHRA’s leadership was baked into the sport. Tice eventually took over AHRA and, in Kepner’s telling, spent much of his career needling Parks in ways that forced NHRA to react.

🔥 48-HOUR SALE! 🔥 Odd-lots, short-lots, closeouts & display shirts — all priced to move! 🏁 Get authentic https://t.co/jcAfIG1TiW gear for as low as $10 👕💥

— Competition Plus (@competitionplus) November 6, 2025

When they’re gone, they’re gone!

👉 https://t.co/ZWQRwUgEQb #DragRacing #NHRA #CompetitionPlus #PEAKSquad #Sale… pic.twitter.com/UOWDUKCRSP

Tice understood leverage. In 1970 he formalized the Grand American Series, which had roots back to 1966, into a 10-race points championship with what Kepner described as “a cash f***ing point series for the world champions, and far more money than they’d ever heard of before.”

It wasn’t six figures, but “it was like 10,” Kepner said, “which was a s***load of money in 1970.” Tice also posted the schedule in advance, booked almost every major star and offered pro starts and structured qualifying sessions before NHRA made those concepts standard.

At the same time, Tice had to manage his relationship with Parks carefully. Kepner said, “The Grand American races were never scheduled on top of NHRA races, and Wally appreciated it,” even if the respect was mostly strategic and often thin.

Beneath Wally’s outwardly cordial treatment of Tice, the rivalry simmered. Kepner said Parks “really protected the NHRA like it was his third fing wife,” while Tice “was a fing businessman… there to make money, period, period.”

Where Tice saw market share, Parks saw a threat to his non-profit mission and a challenge to NHRA’s authority. The tension only escalated when discontented professional racers decided to form their own group and drag Tice into the fight.

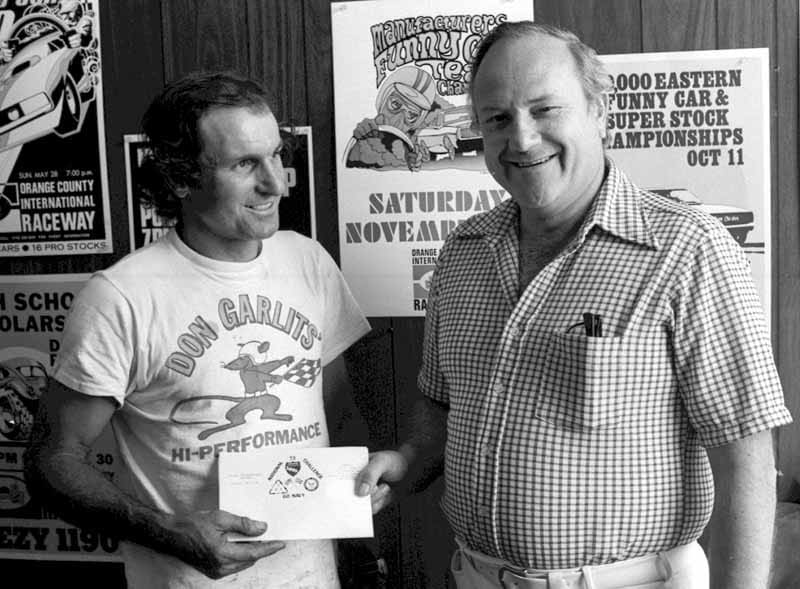

In 1972, Don Garlits and a group of investors launched the Professional Racers Association. They were furious over NHRA purses and politics, and Tice immediately saw an opening to “stick another knife in Wally’s rectum,” as Kepner bluntly put

it.

That breakaway movement morphed into PRA and later PRO events, with Tice sanctioning the races and guaranteeing the purse. The $25,000-to-win Tulsa race became legend for its financial insanity, but it proved a point.

“There was a couple of different reasons for the couple of different people who ran that f***ing race,” Kepner said. Oil money from Gene Snow, family backing from others and Garlits’ anger all fueled the project. “Nobody made any money at the race because you couldn’t charge more than three or four bucks a head to get in… and he had a quarter million dollar purse.”

Rainouts, venue changes and poor crowds only made things worse. By the late 1970s, PRO events were bouncing from Union Grove to Lakeland with diminishing returns and chaotic operations.

But they did force NHRA’s hand. “That’s the only thing that came out of the PRO and the PRA and the PRO races,” Kepner said. “It made NHRA raise its purse.”

If NHRA appeared slow to react to innovation, it was often by design. Kepner said bluntly that NHRA “let the IHRA or the AHRA start these weird things, and they sat back to see if it worked,” then adopted the winners and left their rivals holding the failures.

That attitude extended to how NHRA even spoke about its rivals. Inside the walls at Glendora, IHRA wasn’t acknowledged as a national opponent.

Kepner noted that NHRA officials and National DRAGSTER often reduced IHRA’s national events to “the Match Race Circuit,” as if it were just a string of outlaw shows.

Still, nothing drove the rivalry quite like Carrier himself. By 1970, he and Tennessee State Senator Carl Moore had burned through relationships with both NHRA and AHRA, convinced neither group would ever treat Bristol Dragway the way they believed it deserved.

Their frustration with NHRA’s demands and AHRA’s leadership turned into a bold decision. If they couldn’t get a fair shake from the existing powers, they would build their own.

In 1970, Moore and Carrier founded the International Hot Rod Association, positioning it as a Southeastern-based alternative for working-class racers, match race stars and tracks that felt ignored by the West Coast-centric NHRA and the increasingly scattered AHRA.

IHRA launched its first season in 1971.

Carrier believed drag racing’s future had room for someone willing to challenge both NHRA and AHRA simultaneously. In his view, the South needed a sanctioning body that spoke its language, understood its fans and respected the facilities that anchored its racing culture.

Drag racing wasn’t big enough for three kings, but in 1970, Larry Carrier was convinced he could become one.