John Force didn’t ease into drag racing — he clawed his way in one burned motor, one borrowed sponsor, and one parking-lot burnout at a time. In this installment of In His Words, Force reflects on the chaotic early years that shaped him long before championships and corporate partners ever entered the picture.

Force said his beginnings were far from glamorous. “If I told you the truth, you wouldn’t believe it,” he said. “You’d think I made it all up.”

He insists fans forget how rough it really was. “People don’t know I drove a front engine dragster,” he said. “People don’t know that I drove a fuel altered and rolled it end over end on a back street trying to impress my wife, Laurie.”

But those crashes, blowups, and fires became his identity. “This guy can’t win a race, but he’s on fire every week,” Force said. “But man, he’ll tell you a story.”

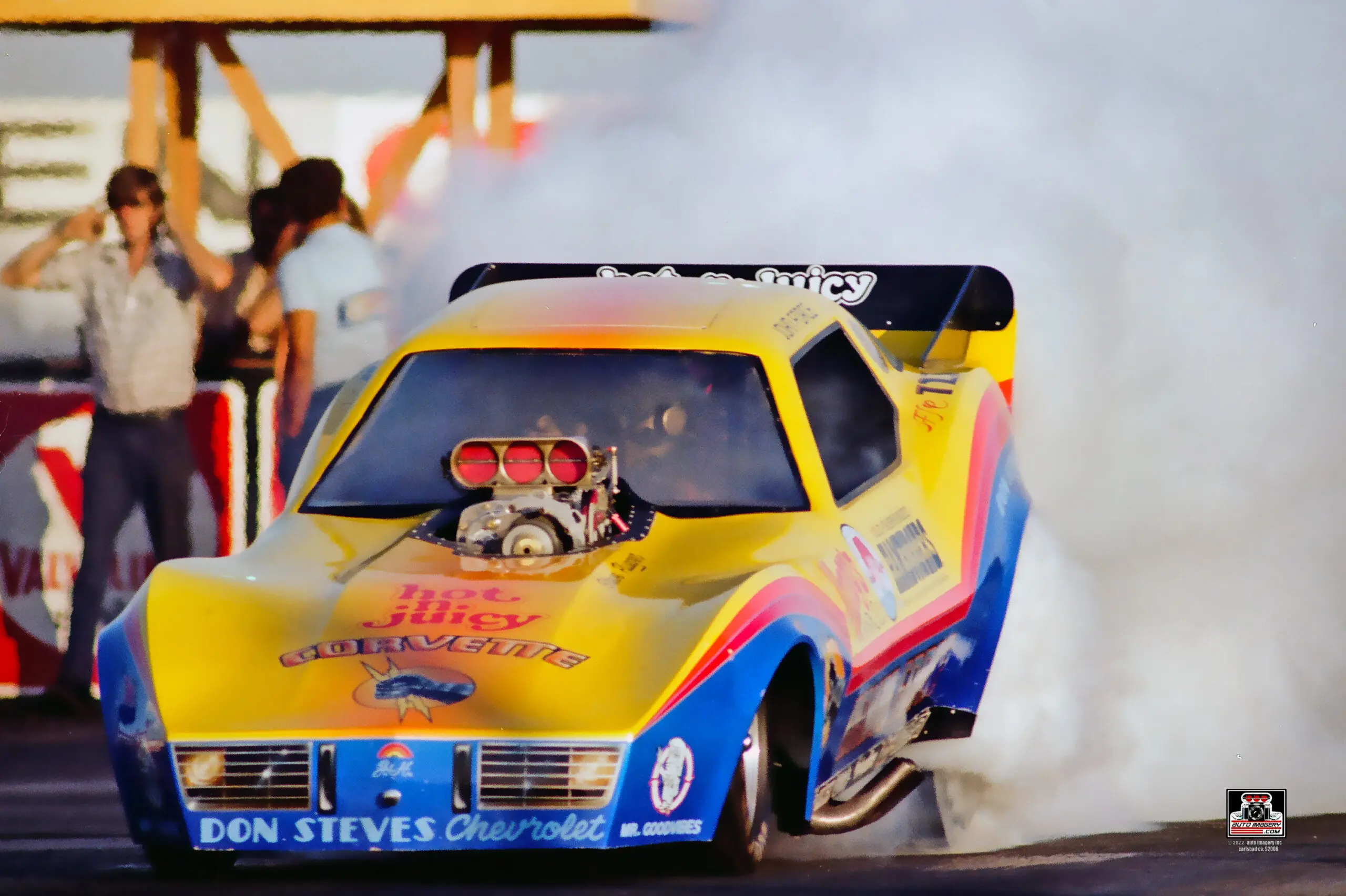

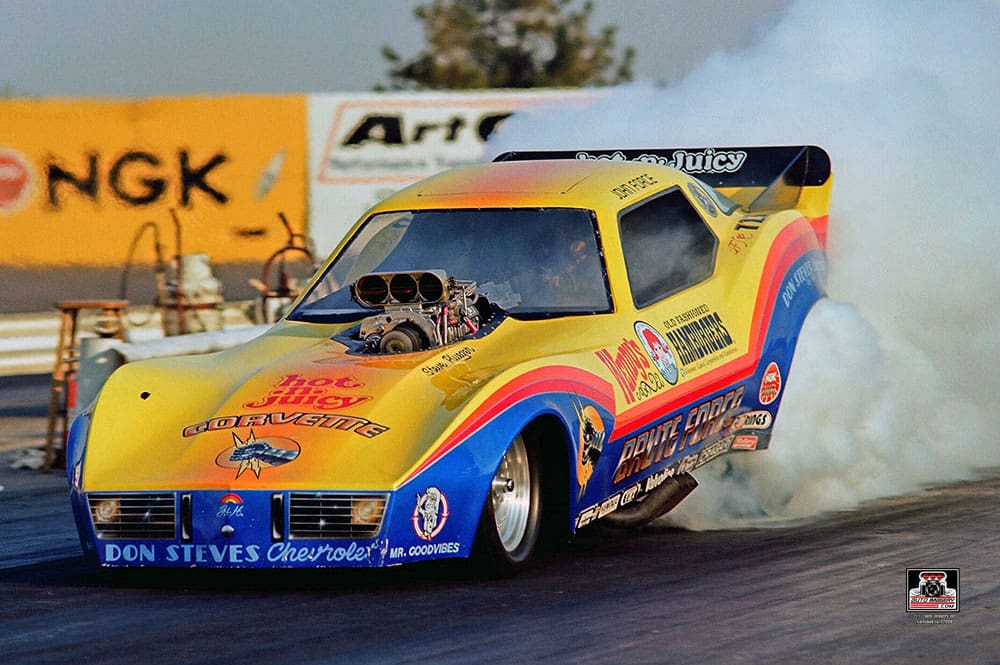

John Force’s definition of “corporate America” bore little resemblance to the polished sponsor boards that eventually lined the walls of his championship operation. To him, early corporate backing came from places like a stereo shop, a new Wendy’s franchise or a local Chevrolet dealership willing to trade a little money for a lot of noise. “Corporate America was a little stereo store on the corner,” he said. “It was an opening Wendy’s Hamburger… It was Don Steves Chevrolet.”

His first meaningful sponsorship came during the mid-1970s, a time when Jaws and The Exorcist dominated theaters and his car performed closer to a horror show than a race machine. “My motors needed an exorcism,” he joked. “They blew up, set me on fire, but that’s why I got famous.” That combination of chaos and charisma drew the first eyes his way.

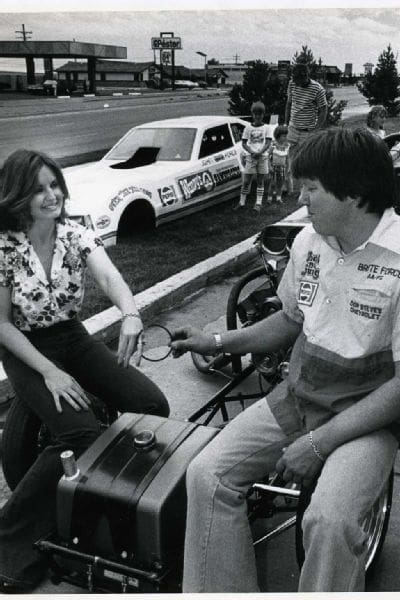

It was that hustle that led him through the doors of Don Steves Chevrolet, where he volunteered to turn the parking lot into a smoke show. “I said, ‘Yeah, I’ll do a burnout in a parking lot,’” Force said. The stunt earned him his first equipment — a ramp truck, a sleeper and $150 a month.

The amount wasn’t much by racing standards but meant everything to him at the time. “My rent was 125,” he said. “Now I can pay my rent.” That small lifeline allowed him to keep racing and living in the same week, something that wasn’t guaranteed then.

Force outfitted his new truck with CB antennas even though he didn’t have a CB radio. He needed to look like the big teams, even if the details were improvised. “I didn’t have a CB, but I had the antennas,” he said. “You had to give that look for corporate America.”

That illusion faded quickly the day a rival crew opened his truck door looking to borrow the radio. Instead, they found nothing but metal and wiring. The moment didn’t shake Force’s confidence, though. He was committed to appearing bigger than he was, because appearance meant opportunity.

His next attempt at finding support came at Wally Thor’s School of Trucking, a place he hoped might offer sponsorship. Instead, he was mistaken for a motivational instructor when Thor realized a trainer hadn’t shown up. “Unless you know how to talk to these kids,” the owner warned. Force insisted, “Yeah, I do.”

He worked the room with humor, stories and confidence, selling truck driving as if he’d been hired to do it. “I entertained them, made them laugh,” he said. The unexpected performance landed him another check, and another piece of the puzzle began falling into place.

Those Saturdays teaching classes blended into nights and weekends match racing at Orange County and Irwindale, giving Force two jobs in one day more often than not. “Now I got another gig,” he said. “Now, John Force Racing has started.” The name existed long before the empire did.

Another unusual break came at Leo Stereo, the shop he often labels one of his earliest true corporate supporters. He walked in seeking a CB radio he couldn’t afford, and instead left with a deal to park his race car at the store, fire it up and draw foot traffic. “I can bring my race car, put it in the parking lot, we can start it,” Force told the owner.

The payment wasn’t cash but drums of nitro — exactly what he needed most. He used some fuel for the appearance and hauled the rest to the racetrack. “Whatever was left in that drum I took to the racetrack,” he said. The system worked, even if it wasn’t conventional.

Wendy’s entered the picture when Force spotted a store sign and cold-called the franchise office. His first sponsorship proposal was returned immediately, full of red ink and corrections. “The spelling’s terrible, this is terrible,” he remembered. Laurie rewrote it, and the improved version secured him a deal.

That deal existed not because of his performance, but because a Wendy’s marketing executive wanted to break into announcing. “They didn’t even care if I raced,” he said. His role was to help get the man in front of industry decision-makers.

Life on the road was never smooth, a truth crystallized during one long highway trip when Laurie smelled something burning beneath the truck. “Her feet have melted to the floorboard through the carpet,” Force said. A blown muffler had turned the floor into a slow-cooking hazard.

The noise from the muffler was relentless. “Bap, bap, bap, bap, bap,” he said. Laurie wore earphones to dull the pounding as they limped along, their trailer overloaded and tempers tested.

The road was barely behind them when they arrived at a loose racetrack and discovered they lacked the proper spoilers for traction. “We don’t have any spoilers,” one crew member said. The track conditions demanded a fix.

Force found it in the form of a metal Bank of America sign hanging from a chain nearby. “We borrowed the sign,” he said. Necessity made the decision for him.

He cut the panel into pieces, wrapping one part around the blown muffler to silence it and using the section marked “B of A” to build makeshift rear spoilers. “That’s the truth,” Force said. “That’s how we did it.”

When they rolled into Baton Rouge, the announcer saw the Bank of America letters and declared, “John Force looks like he signed a deal with Bank of America.” The claim was as accidental as it was inaccurate. “I never did get a deal,” Force said.

His marketing approach had always relied on improvisation. He once painted “Coca-Cola” on his car without authorization, hoping the name alone might create opportunity. “I never got a penny from it,” he said. But it drew attention from Stop and Go Markets, which approached him because they believed Coke was already involved.

The strategy eventually paid off, with Coke providing real support later. It was one more example of how Force leveraged creativity to fill gaps money couldn’t cover.

His relationship with Wendy’s deepened during the era when Don Prudhomme was their national star. Franchise owners wanted local appearances on Fridays, even during race weekends. Prudhomme couldn’t do it — so Force stepped in. “So they sent me all the way from California,” he said.

While other racers were at the track, Force was in Wendy’s parking lots, revving engines and greeting customers. “We were eating hamburgers,” he said. The work came with a cost, as he missed the first qualifying session but made the second.

They didn’t qualify, but the displays mattered more to the franchise operators than the ladder sheets. His presence brought customers and energy to the stores. “There was still a little place for John Force,” he said.

On track, the learning curve remained steep. In one round, he made the fundamental mistake of leaving the starting line in high gear. “That’s a killer to be that dumb,” he said. The miscue seemed guaranteed to end his day.

Instead, he managed to recover enough to win. “The Lord just let us pull that one right out of the bag,” Force said. It became another story in a career built on escapes and improvisation.

Force credited a long list of people for helping him survive those early days, including a banker who hid checks in her shoe when rainouts prevented him from covering them. “Don’t think that stuff don’t happen,” he said. Support came from unexpected corners, and every instance mattered.

Force said today’s operation — the trailers, the payroll, the fleet of cars — was built on the foundation of those unpredictable years. “Every time I get stupid and start thinking I’m a big shot and I’m Superman, I think about how I got here and the people that helped me,” he said.

Seeing the legends he once admired always humbled him.

“I said, ‘Oh man, this must be heaven,’” Force said, recalling moments where he stood among Prudhomme, Beadle, McEwen, Lombardo and Pisano at the legendary Bill Doner roast in 1980.

The sentiment didn’t last long before humor returned. “And Doner walks through the door and I said, ‘It blew this deal,’” he said. Even his awe came with a punchline.

His journey, he emphasized, wasn’t linear. It was messy, loud, unpredictable and dependent on the kindness of people who believed in him before the record books did.

“There was a lot of good people along the way,” Force said. “Helped me get here.”