John Force didn’t ease into drag racing — he clawed his way in one burned motor, one borrowed sponsor, and one parking-lot burnout at a time. In this installment of In His Words, Force reflects on the chaotic early years that shaped him long before championships and corporate partners ever entered the picture.

Force said his beginnings were far from glamorous. “If I told you the truth, you wouldn’t believe it,” he said. “You’d think I made it all up.”

This edition concludes the three-part series, and it’s at a time when Force was seemingly knocked off the pinnacle. You will see the fight that was established as early as 1979.

In 2016, John Force was no longer fighting for another title. He was fighting for the right to decide his own ending.

The pressure did not come from the grandstands or the record book, places Force had learned to navigate decades earlier. It came from inside the pits, where a handful of uneven runs the season before had turned into questions about whether the sport’s most successful Funny Car driver still belonged behind the wheel.

Drivers raised concerns with NHRA about Force’s ability to handle a race car, and one competitor openly wondered why he continued when he had nothing left to prove. That question cut deeper because Force had already proven everything there was to prove.

The doubts landed during a season of real instability, both competitive and financial. Force had lost longtime sponsors Castrol and Ford, and the optics suggested a champion slipping toward the margins.

To some, it looked like decline and inevitability. To Force, it felt like others were quietly trying to decide when his career should end.

He did not hear concern in those conversations, no matter how carefully it was framed. He heard a polite form of mutiny.

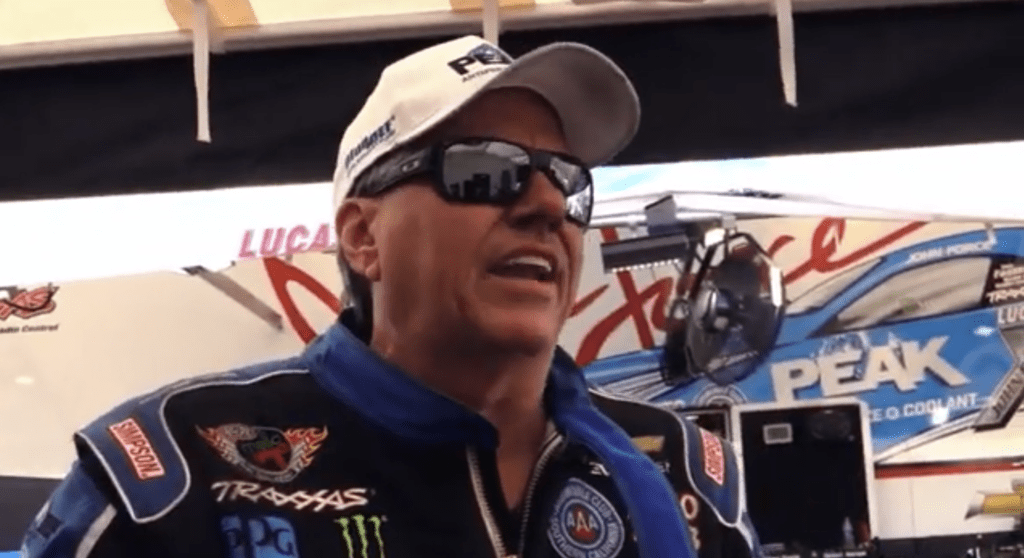

When a camera crew approached Force for an interview, he was already running hot and fully aware of the moment. He had just finished a Monster Energy drink after what he later joked was likely a dozen cups of coffee.

Force knew he was “on the chip,” and he knew exactly why. The questions circling him were no longer about history or accomplishments, but about relevance and permission.

What followed became one of the most shared and dissected moments of his career, precisely because it was raw. It was not planned, scripted, or restrained.

The outburst resonated because it revealed something that had never left Force, no matter how many championships he stacked. He has always understood the fight as something deeper than racing.

Sylvester Stallone once summed it up in a line Force says mirrors his own life: “You, me, or nobody is going to hit as hard as life… but it ain’t about how hard you’re hit, it’s about how hard you can get hit and keep moving forward.”

To Force, that was not movie dialogue meant for a montage. It was lived experience, earned the hard way.

“I know this ain’t what you’re asking, but you got me wound up now,” Force said as the interview began, making no effort to soften his tone. He did not try to dial it back.

“I drank some of that Monster. I’m all wound up and I’m going to say some things and get it off my chest and move on,” he said. Then he reached for an analogy that has haunted him more than any crash.

Force spoke about the Babe Ruth story, the moment when the bat is handed to the next kid and the spotlight shifts. “That time will come someday,” he said. “And that scares me to death.”

“That scares me to death because I love it out here,” Force said, explaining the emotion beneath the anger. “I’m 66 years old, okay?”

He made it clear there would be no ceremonial exit built around nostalgia. “As long as I can pass the physical, as long as I can be out here, I’m going to do this,” he said.

“There will not be a final tour for me,” Force added, drawing a hard line. “If it’s going to be a final tour, it’s because I leave the racetrack and I never come back again.”

“I’m not saying goodbye,” he said. “I got nowhere to go.”

Force explained that home had never been a single address or a fixed place on a map. Hotels, racetracks, and return roads had filled that role for more than five decades.

“I’m so used to hotels, that’s my home,” Force said. “When I get to the racetrack, I feel like I came home.”

“This is 50 years of Funny Car,” he said, placing himself inside the sport’s arc. “I helped build Funny Car.”

He spoke about generations the way fighters do, without resentment but with clarity and acceptance. “With some young kid, some young gun, they go up to the old cowboy and say, ‘Let’s fight,’” Force said.

“That’s what this game’s all about,” he continued, widening the lens. He said the same dynamic exists everywhere, not just in racing.

Force said championships do not come from part-time commitment or borrowed intensity. “What makes a champion is somebody that lives it,” he said.

“That lives it seven days a week, 24 hours,” Force added. “You sleep and dream it.”

He acknowledged luck and the people who helped him along the way, but not at the expense of the grind itself. “I’ve got the most wins,” Force said. “Was I lucky? Probably.”

“But I lived it,” he said, returning to the point. “And that’s why I’m still here.”

The fire that surfaced in 2016 was not new or manufactured. It was muscle memory.

It was the same instinct that carried Force through his first full season on tour in 1979, when the idea of his name becoming a brand would have sounded absurd. Back then, he was not fighting for legacy.

He was fighting to eat, to reach the next track, and to survive another weekend. He was fighting because quitting made sense, and choosing not to quit required something deeper.

And that is where the foundation was laid.

🏁 Angelle Sampey finally made her first run in a Top Fuel dragster — and it was more than a test session. It was a promise, a month of fear and second-guessing, a crash she witnessed moments before climbing in, and then a calm that hit the instant the car fired like she’d been… pic.twitter.com/GenoSPCWbX

— Competition Plus (@competitionplus) December 17, 2025

The version of John Force that erupted in 2016 was forged in a year when survival mattered more than optics, when making it to the next race was never guaranteed. That year was 1979, his first full season on the tour, when the idea of longevity felt almost irresponsible.

Force probably signs more autographs in a single weekend now than he did during the entire 1979 season, a contrast that still registers when he looks at the rope line outside his pit. He understands how completely his life has changed, but he also remembers when that rope would have been unnecessary because there was no crowd to hold back.

“I have to take care of the fans,” Force said as he walked with a slight limp toward a mass of people standing four rows deep, arms stretched forward. The responsibility still surprises him, even after decades of living inside it.

Some days the fans get the full autograph, with most of the letters in his name legible, and other days they get the trademark “JF” when the line never seems to end. In 1979, there were days Force would have paid someone to ask, when money was tight, fans were few, and attention usually arrived only when something went wrong.

Force did not care about that reality at the time, choosing instead to chase an NHRA Winston World Championship on instinct alone. It was one of the worst and best decisions of his career at that point, bad because he barely had the resources to run half the schedule and good because it produced his first career top-10 points finish.

That result became the foundation for a streak that eventually reached 24 consecutive top-10 finishes, though at the time it simply meant he had survived. The first season also delivered a moment that still makes him laugh, when a fan walked into his pit area and asked for an autograph.

“They didn’t know any better,” Force said, noting that he now averages more autograph seekers in one weekend than he did that entire year. “Most of them were trying to drag me through the ropes back then, now I’m trying to get away from them to do other things.”

“That’s good,” Force added. “That’s what the fans are all about.”

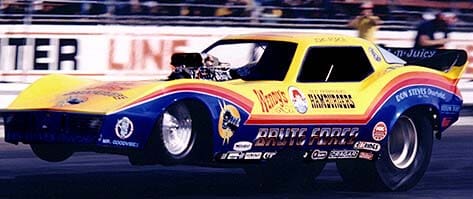

Fans eventually meant sponsors, but not in 1979, when Force had more sponsor decals than people watching the car. One deal was based largely on free food rather than cash, an arrangement Force admits made sense at the time.

“I really never thought drag racing would be what it is today back in 1979,” Force said. “What I can remember of 1979.”

Selective memory helps, he admits, because there are incidents he will not discuss and others that explain enough on their own. One involved dressing as the Wendy’s girl to replace a no-show at a sponsor appearance, with Force’s only regret being that he did not have time to shave his legs before race day.

The pit compound in 1979 bore no resemblance to the modern operation, and travel itself was often as memorable as the racing. Force recalls a faulty exhaust system in the tow truck melting his wife’s shoes to the floorboard, a problem his brother Louie fixed using sheet metal taken from a Bank of America sign.

The leftover metal became a spoiler on the car, and a local newspaper later reported Force had signed a new sponsor. It was an unintentional example of how perception could sometimes outrun reality.

Force begged, borrowed, and did everything short of stealing to keep racing that season, often winning money already earmarked to pay debts incurred simply to reach the next event. That was the Force way in 1979, and even now he shakes his head when he talks about it.

He became known for borrowing money inside the pits, leaving creditors uncertain they would ever be repaid. “I had hocked everything,” Force said. “I borrowed a great deal of money from someone well known in the pits.”

Force said the lender believed he was going to cheat him, so he sent a collector known as the “Quarter Bender.” The nickname was not metaphorical.

“When they said he could bend quarters, he could bend quarters,” Force said. “Ole John Force was going to fight this guy,” an idea that did not age well even in the retelling.

Warnings followed that the Quarter Bender had stuffed another man into a trash can, prompting Force’s uncle Gene to intervene. Gene enlisted George Stregal to contact the collector’s father and explain that Force was an up-and-comer who was too stubborn to know when he was in real danger.

“He told him I was too stupid to know he was going to kill me,” Force said, adding that he settled the debt late but alive.

The operation itself was as improvised as the finances, with Force often running what he described as a crew chief by committee. According to sources from that era, he sometimes included fans at the pit rope in tuning discussions, simply because another opinion was better than none.

When money existed, help rotated in, with Bill Schultz and chassis builder Steve Plueger occasionally filling those roles as favors tied to family connections. “We didn’t even have uniforms,” Force said. “We had Wendy’s store T-shirts.”

“No one knew what a square hamburger was,” he said, noting that he became the embodiment of the product whether he intended to or not. Force sold himself larger than reality, and when company representatives showed up, they often left confused by what they saw.

Then came the race that made everything feel possible, when Force won his first career round by defeating Tom “Mongoose” McEwen. That same weekend, he reached his first final at the Cajun Nationals in Baton Rouge, a result that shocked no one more than Force himself.

“I thought my ship had come in,” he said, before reality arrived in the form of Kenny Bernstein and the Chelsea King Plymouth Arrow. “There I was, I felt like I was going to spank Bernstein,” Force said, until the transmission broke.

“It didn’t matter,” he added. “I probably would have lost anyway.”

Force later finished runner-up again at the Summernationals in Englishtown, losing to Raymond Beadle, another driver headed toward a championship career. At the time, no one knew what Force would become, including Force himself.

His charisma showed early, particularly in an interview with announcer Steve Evans following a round he admitted he should have lost. When Evans suggested Force might have lost had he not stuck with it, Force responded with the honesty that would become his trademark.

“Steve, I made one of those all-time screwups,” Force said. “I left the starting line in high gear.”

He apologized to his crew and credited luck, saying, “The Lord allowed us to pull that one out of the bag.” When Evans suggested he would never do that again, Force disagreed, saying, “I’ll make a lot of mistakes before this is over.”

The smile from that interview returned in 2008, in St. Louis, as Force approached his 1,000th round win. Looking toward the Gateway Arch, he remembered how often St. Louis marked crossroads in his career, moments when being broke and close to quitting felt permanent.

“When a man eats his last old baloney sandwich under the truck seat,” Force said, “he’ll do just about anything.” One day, that meant driving through a heavy fog while safer teams refused to run.

The promoter panicked and turned to Force, telling him he had to run or he would not get paid. Today, Force would refuse, but then he had no choice, and he drove through the fog to survive another weekend.

Thirty years later, Force reached his 1,000th round win with Ron Capps as the milestone opponent. “Lots of memories ran through my head,” Force said, admitting he could not shake the fog.

He said the win was not just for him but for the fans who had followed the journey. “God didn’t have to give me 1,000 wins,” Force said. “That was for the fans.”

Force’s story has always been about refusing the easy exit, a refusal that connects 1979 directly to 2016. What sounded like anger that season was recognition, the same instinct that carried him through hunger, fog, and doubt.

Not after 1979.

Not after the fog.

And not after everything that followed.