For a brief but consequential stretch of American motorsports history, some of NASCAR’s biggest names spent their off-days drag racing, not as a novelty but as a practical way to earn money and extend their reach with fans.

The period, roughly from 1957 through the mid-1960s, coincided with drag racing’s rapid rise and a time when stock-car schedules still left openings for drivers willing to travel to small tracks and race head-to-head for appearance money.

Noted drag racing historian Bret Kepner said the motivation was straightforward and widely misunderstood. “It had nothing to do with engines being banned,” Kepner said. “The reason those NASCAR drivers went drag racing was money.”

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, NASCAR purses were improving but not yet booming, while drag racing promoters were paying guaranteed match-race fees to bring recognizable names to town.

Tracks understood that fans knew the stock-car stars, even if drag racing itself was still establishing national heroes. Promoters booked those names for best-of-five match races against local favorites or other touring stars.

Kepner compared the practice to earlier eras when promoters used celebrity racers to draw crowds. “It was no different than what happened decades earlier when promoters used famous drivers simply because people recognized them,” he said. “They were selling familiarity.”

The class of choice for those crossover drivers was Super Stock, the dominant drag racing category of the era and one that rewarded consistency and mechanical discipline rather than radical experimentation.

Using Fred Lorenzen as an example, Kepner explained how manufacturers saw drag racing as a marketing opportunity. Lorenzen was closely aligned with Ford, and the company understood that drag racing crowds were growing faster than stock-car audiences at the time.

Ford placed Lorenzen in a Super Stock car and sent him on the match-race circuit, capitalizing on his NASCAR fame. Tracks paid to see him, and fans responded, even if drag racing’s own stars had not yet become household names.

The approach worked precisely because Super Stock racing was heads-up and relatable. There were no indexes or brackets, only first to the finish line, which made it easy for fans to understand and promoters to sell.

According to Kepner, many of these drivers raced heavily between 1961 and 1964, often within a defined regional footprint rather than nationwide tours.

Most match racing took place in the Southeast—Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, and Florida—with occasional ventures farther north. The economics favored short hauls and frequent appearances.

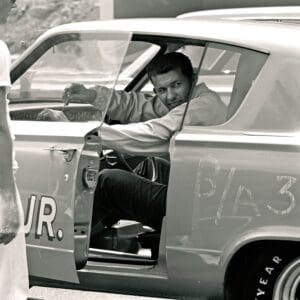

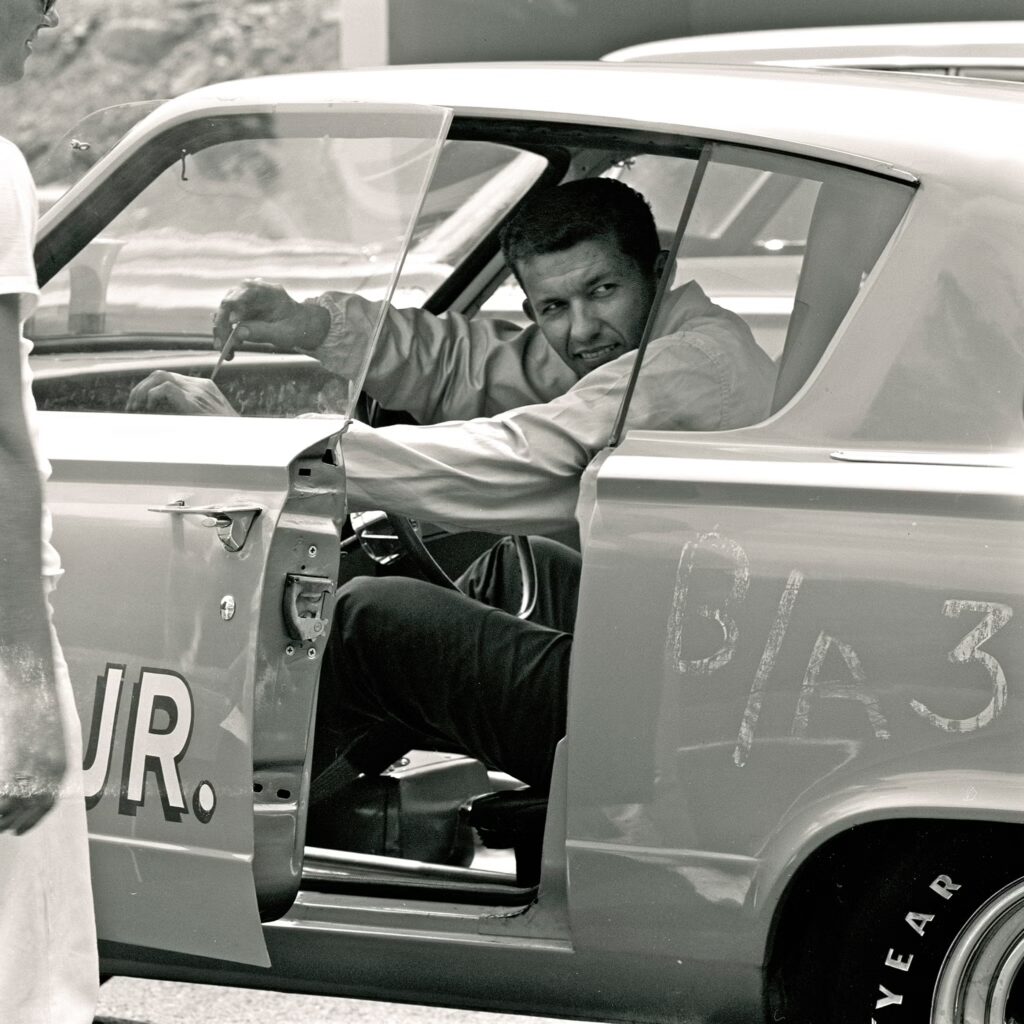

Among the most persistent myths from the era is the belief that Richard Petty turned to drag racing because of NASCAR’s Hemi restrictions in 1965.

Kepner said that narrative ignores years of history. Petty began drag racing in 1959 and continued almost uninterrupted through the mid-1960s, long before the Hemi controversy became a talking point.

Petty raced drag cars in 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, and 1965, often while still actively competing in NASCAR. Drag racing was not a reactionary move; it was a parallel career.

His final drag race came in early 1966, shortly before the Daytona 500, and Kepner said the reason for his departure was logistical rather than philosophical.

By that time, NASCAR’s calendar had expanded to the point that there were few, if any, off-weekends. To compete for championships, drivers had to attend nearly every race, including events on smaller dirt and paved tracks.

“There just wasn’t time anymore,” Kepner said. “Once NASCAR became that demanding, drag racing had to go.”

Petty’s drag racing also produced enduring misconceptions about the cars he drove and the classes he ran.

Kepner emphasized that Petty competed in Super Stock, not Factory Experimental or early Funny Car categories, which did not yet exist in their later-defined forms.

When Petty appeared at NHRA’s 1965 Bristol event, the class was called Match Bash, a catch-all eliminator for cars that did not fit neatly elsewhere.

Petty’s Barracuda ultimately ran in B Altered because that was the only legal placement available. While competitive within its classification, it was not built to challenge the quickest match racers of the day.

He ran on gasoline, not nitromethane, and did not have the tuning sophistication of the fastest cars in the field. Kepner said Petty was fulfilling a booking obligation rather than chasing overall honors.

“He was there because he was booked,” Kepner said, “not because that car was meant to be the quickest thing in the pits.”

Match racing pairings varied widely depending on promoter ambition and geography.

Sometimes promoters staged headline attractions such as Lorenzen versus Petty. Other times, a national NASCAR name faced a respected local racer to ensure strong gate attendance.

Parnelli Jones was a unique case because he was based on the West Coast. Instead of hauling a car across the country, he often rented a Super Stock car locally, splitting the purse with the owner.

Jones would fly in during race weeks, run multiple drag events at tracks near major NASCAR venues, and then transition directly into stock-car competition.

Kepner cited Georgia as a prime example, where Jones frequently raced at Yellow River and Covington in the days leading up to major NASCAR events in Atlanta.

“He would race Saturday, Sunday, even midweek, make some money, and then go run the NASCAR race,” Kepner said.

Another persistent rumor suggests Petty left drag racing after a crash, but Kepner said the facts point elsewhere.

Petty raced again almost immediately after the incident, bound by a full calendar of booked appearances. Drag racing income was essential at the time, particularly during periods when he was not competing in NASCAR.

Petty campaigned two blue 1964 Barracudas, the first carbureted and the second fuel-injected, both built specifically for drag racing.

Kepner said the crash has overshadowed a broader and more significant drag racing résumé that began with Chevrolet-powered entries and evolved alongside Chrysler’s most competitive offerings.

Petty’s relationship with the manufacturer ensured access to the latest engines and platforms, which kept his drag racing program current year to year.

“He always had the newest piece,” Kepner said. “Whatever was the strongest combination at the time, that’s what he was running.”

David Pearson also participated extensively, particularly within the Carolinas and nearby states.

Unlike some factory-backed stars, Pearson often operated without a formal manufacturer deal in drag racing, adding another layer of practicality to his participation.

Pearson’s appearances tended to be more frequent than those of some contemporaries, reflecting both regional ties and the financial appeal of consistent match racing.

Kepner noted that both Yarborough brothers also took part, again in Super Stock machinery rather than factory experimental configurations.

Confusion over terminology has muddied the historical record, Kepner said, especially the retroactive application of “FX” labels that did not align with period rules.

“Super Stock then was essentially heads-up racing,” Kepner said. “It was closer to what people later understood as Pro Stock than anything experimental.”

As the decade progressed, structural changes in both sports closed the window on widespread crossover.

NASCAR teams began building multiple cars for different tracks, increasing shop demands and travel logistics.

At the same time, drag racing developed clearer class distinctions and a growing roster of specialists who made full-time careers at the strip.

The combination made it increasingly impractical for stock-car stars to split their focus without compromising results in either discipline.

By 1966, the era had effectively ended, not because of bans or crashes, but because professionalization left no margin for divided attention.

“They didn’t quit because they wanted to,” Kepner said. “They quit because the schedules made it impossible.”