Ron Capps was not born with a silver spoon or a guaranteed place in drag racing’s professional ranks. What he carried instead was proximity to the sport, patience for its grind, and the understanding that opportunity only matters if someone is ready when it appears.

Capps detailed that reality during his appearance on the debut episode of The Alan Reinhart Show, offering a rare, unfiltered account of how his career actually began — and why longevity in drag racing has far more to do with work ethic than trophies.

The moment many fans assume was the beginning did not arrive with a helmet fitting or a Funny Car contract. It arrived with a phone call, an airline ticket, and a problem Capps never expected to admit aloud.

When Don Prudhomme invited Capps to meet prospective sponsors, Capps said he did not own a suit. He did not even own a sport coat.

“Lynn Don Prudhomme sent me 350 bucks, Western Union,” Capps said. “I went down and bought my first ever suit.”

That meeting ultimately led to Capps driving a Funny Car, but he made it clear the invitation itself was earned over years of being present, helpful, and visible in Division 7 drag racing. The call came only after Prudhomme had been watching closely.

Capps grew up in San Luis Obispo, California, where weekends meant Santa Maria, Bakersfield, Fremont, and anywhere else racing happened. His father’s garage became a hub for racers looking for help, turning the family driveway into a rotating paddock.

Cars came and went, but lessons stayed. Capps said he learned early that improvement came from repetition, observation, and being useful long before being noticed.

When his father sold their race car, Capps stayed involved by working with Jim Rizoli’s team, tagging along and learning without the benefit of a driver’s seat. That commitment eventually paid off with a Division 7 championship and deeper exposure to the sport’s inner circle.

Still, Capps never mistook effort for entitlement. Without family money or sponsorship backing, he understood driving opportunities were rare and often accidental.

“I knew my only chance was going to be a lucky shot,” Capps said. “And somebody would have to give me that shot.”

Before that chance arrived, Capps supported himself teaching racquetball across Northern California while attending college. He played tournaments for money, considered a career in software engineering, and acknowledged that Silicon Valley offered a safer future.

Racquetball, like racing, forced a hard truth. Being good was not enough to build a career.

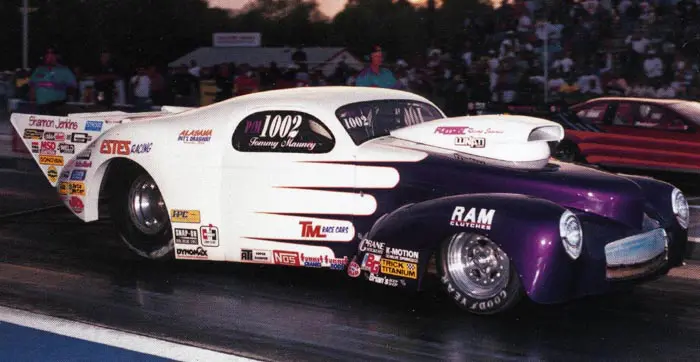

That reality changed when John Mitchell offered Capps the opportunity to license and drive an alcohol dragster. Capps quit his crew role immediately and drove to Montana to take the seat.

From there, the progression accelerated quickly. Performance and composure drew the attention of Terry Manzer and Roger Primm, placing Capps in situations where higher-level decision-makers were watching.

Years spent working on cars sharpened his instincts behind the wheel. Knowing when something felt wrong, when to lift, and when to save equipment became survival skills rather than theory.

The Prudhomme call arrived during one of the most chaotic stretches of Capps’ personal life, with a child on the way and medical scheduling built around race weekends. Even then, Capps never hesitated.

He hung up on Prudhomme at first, convinced someone was playing a joke. Only after Prudhomme’s wife called back did the gravity sink in.

The Copenhagen sponsorship launched Capps into Funny Car racing, but he rejected the notion of instant success. Years of groundwork preceded that moment, and he wanted that understood.

Later, Capps addressed a misconception that has followed him throughout his career — that long-term sponsorships are the result of winning alone. He said nothing could be further from the truth.

“It’s hard enough to get a sponsor,” Capps said. “But it’s so much harder, times a hundred, to keep one.”

That philosophy framed his 19-year relationship with NAPA, which he described not as corporate alignment, but as personal responsibility. Capps said understanding the people behind the brand changed everything.

NAPA, he explained, is built on independent store owners, not faceless executives. Each relationship matters because each owner represents the brand daily in their own community.

“I wake up in the morning and, how can I be better for that company?” Capps said.

That mindset, he said, required relentless travel, small-store grand openings, banquets, dinners, and flights that rarely ended at home. None of it showed up on timing sheets.

Wins, Capps said, are icing on the cake. Relationships are the foundation.

The story of how some of those relationships became legend illustrated his point perfectly. One of drag racing’s most recognizable starting-line traditions began without a marketing plan, a strategy session, or permission.

It began with BRUT cologne and a prank.

During his early time with Don Schumacher Racing, a large BRUT bottle was brought to the track as a hospitality display. The bottle was real, filled with cologne, and intended only as a visual prop.

“Well, it’s filled with BRUT, and it’s like this big,” Capps said. “And Ed was a jokester.”

While waiting to fire the car, McCulloch sprinkled BRUT into the header pipes as a joke. When the engine warmed, the heat atomized the cologne instantly.

“And we warmed the car up and it instantly got hot with the headers and it just went everywhere,” Capps said.

The run that followed produced a low elapsed time. The coincidence was enough to turn the prank into routine.

“And so he’s like, ‘Shoot, I better do it again,’” Capps said. “And how can we not do it?”

What followed was not branding genius, but superstition reinforced by results. The team repeated the ritual every run, not because it looked good, but because the car kept winning.

When the wind cooperated, fans in the grandstands caught the scent. When it didn’t, competitors standing nearby absorbed it instead.

“If you weren’t careful when you were walking around the car before it fired at the starting line, and the wind was right, that first puff when they pulled a mag wire would soak people,” Capps said.

Rival teams joked about countering the scent with their own cologne. None of it was planned, but all of it stuck.

“It was actually accidental,” Capps said.

That accidental tradition illustrated the larger truth Capps kept returning to: drag racing success is built in small, human moments that accumulate over time.

Modern racing, he said, has added new risks. Social media now amplifies both opportunity and mistakes.

“You can do a thousand things right,” Capps said, “but one thing wrong could erase 998 of those things.”

He said awareness and restraint have become as critical as reaction time. One careless post can undo years of trust.

As he prepares for another season that includes mentoring Maddi Gordon and returning to the cockpit himself, Capps said the work still excites him. The responsibility still matters.

For Capps, success never arrived overnight. It showed up because he stayed close to the sport long enough — and worked hard enough — for someone to notice.