PART ONE – 50 YEARS OF REHER-MORRISON – A GOLDEN ERA

PART TWO – 50 YEARS OF REHER-MORRISON – WINNING DEFINED

PART THREE – 50 YEARS OF REHER-MORRISON – WHEN LEGACY TRUMPS TRAGEDY

Lee Shepherd was firm in his statement, and David Reher, based on their relationship up until that point, had no other choice but to take him at his word.

Lee Shepherd was firm in his statement, and David Reher, based on their relationship up until that point, had no other choice but to take him at his word.

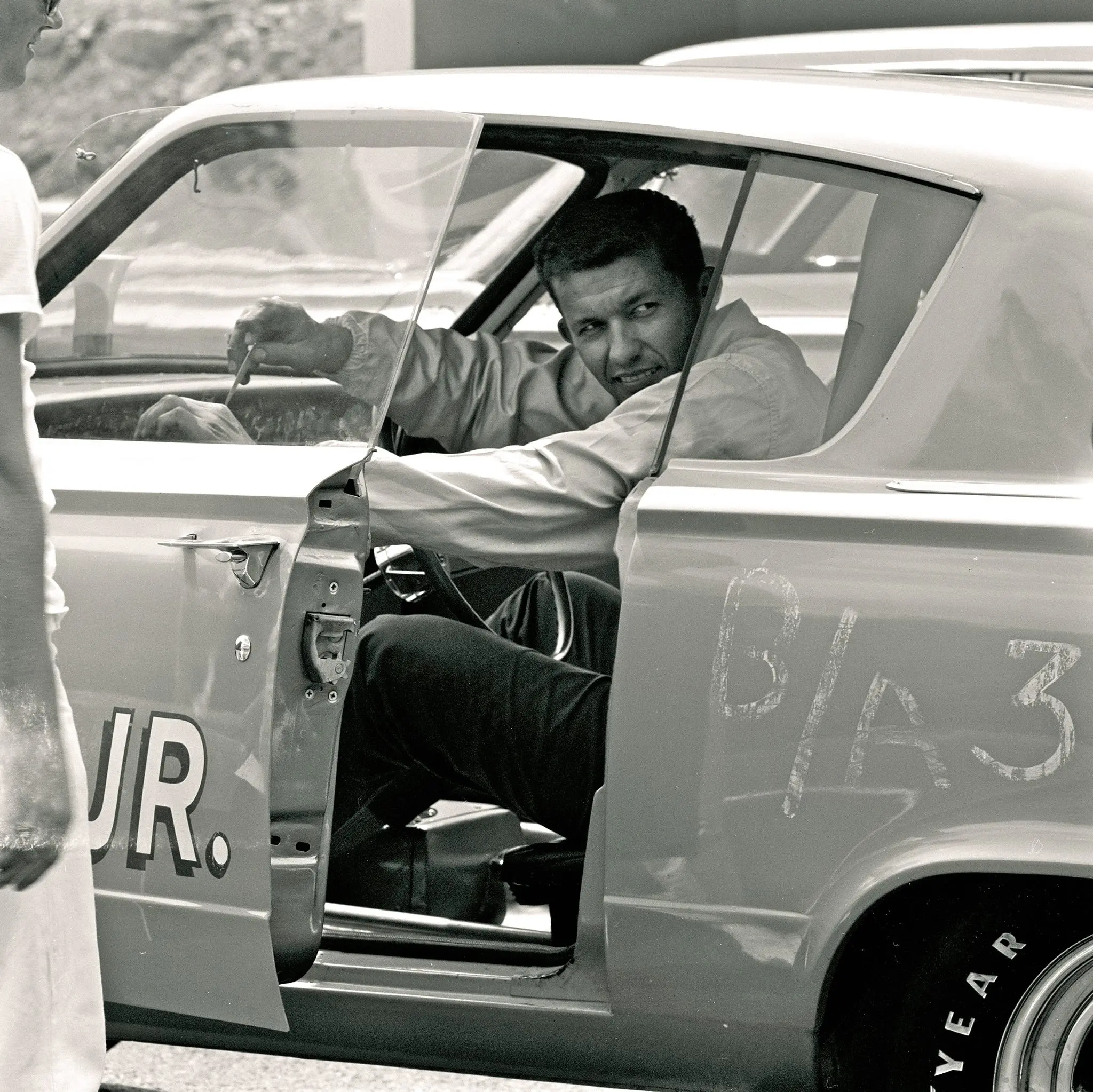

Shepherd had crashed while racing the Reher-Morrison Pro Stocker at the 1976 NHRA Summernationals in Englishtown, NJ, and amid pressure from his family, decided to retire from driving a race car.

Shepherd stood before Reher and told him, “I want back in.”

Reher responded, “Are you sure?”

“Positive,” Shepherd responded.

This interaction took place almost a year after the crash, and Shepherd felt he could no longer stand life on the sidelines. As he saw it, he was destined to be in a race car.

Reher and Morrison had a gentleman’s agreement with Richie Zul and intended to finish the 1977 season. But as soon as the year ended, Shepherd was ready to resume his role with the Arlington, Texas-based team.

Reher said the team took delivery of a new Camaro for 1978 from Don Ness, a car that inspired a long line of the larger, longer wheelbase and more stable alternative to the Monza, immediately got the attention of the veterans, notably Bill “Grumpy” Jenkins.

Reher said the team took delivery of a new Camaro for 1978 from Don Ness, a car that inspired a long line of the larger, longer wheelbase and more stable alternative to the Monza, immediately got the attention of the veterans, notably Bill “Grumpy” Jenkins.

Right out of the box at their debut event, an NHRA Division 4 points race at LaPlace Dragway in Louisiana, Shepherd drove his way to a new 162 mph speed record.

“[Jenkins] got so mad because we kind of came from nowhere,” Reher said. “He hooked his rig up and loaded up; he’s slamming stuff around.

And he pulled out that was back when everybody had a Duallie in the Chaparral, and he didn’t hook up his fifth wheel and just yanked the tailgate right off that thing, trying to leave the track.”

The performance might have come as a surprise to Jenkins, but to the Reher-Morrison team, an 8.75 in testing their small-block Camaro the week earlier in San Antonio told them all they needed to know. They had a player in the bid to win a championship.

“We ran good back in 1978, but not good enough – we’d qualify fifth or sixth or sometimes,” Reher said. “We decided we got to get this thing running, or we need to quit. We’d run AHARA and won all those races, but we just need to get to where we can win [NHRA] races. So we went to work on it real hard.”

“We ran good back in 1978, but not good enough – we’d qualify fifth or sixth or sometimes,” Reher said. “We decided we got to get this thing running, or we need to quit. We’d run AHARA and won all those races, but we just need to get to where we can win [NHRA] races. So we went to work on it real hard.”

The Winter of 1979 sent Reher, Morrison, and Shepherd down a different pathway. Feeling there was no substitute for size, they began developing a big block combination. A funny thing happened on the way to change; their small block began stepping up. By 1980, they were on the cusp of being a front-runner.

“The big block wasn’t done yet, and we went to Pomona with a small block and we won Pomona.,” Reher said. “Then we won Gainesville, and then we won the Cajun Nationals. We won three in a row. But we kept waiting on the shoe to drop and everything to come to a screeching halt.”

Nobody won three in a row in those days unless they were from Whiteland, Ind., and their last name was Glidden.

Nobody won three in a row in those days unless they were from Whiteland, Ind., and their last name was Glidden.

“After Gainesville, Glidden came over to us and said, “This is the last time you’re going to see this Chrysler. I’m going back to my Ford.”

“Well, he did, he showed up at the Cajuns in his Ford, and he was a good solid instantly .05 to .06 quicker.”

Glidden qualified No. 1, and while Shepherd still won the race and did so on a holeshot, they knew they needed to hit the next level in a hurry.

“We’re riding home from there. in the Duallie talking and said, ‘Man, we got to get that big block running,” Reher recalled. “We got a taste of winning races.”

“I had slowed the big block [developent] down a little small because the small block was running well; I’m being the conservative one, ‘This thing is running pretty good Why don’t we run it?”

“But after Glidden did that, everybody knew we needed to run hard on this. We had a pretty good start on it, figured out a lot of stuff about it, using the 348 cranks, and had a local core supplier Bishop over in Dallas to spot the best blocks he could for us.

“But after Glidden did that, everybody knew we needed to run hard on this. We had a pretty good start on it, figured out a lot of stuff about it, using the 348 cranks, and had a local core supplier Bishop over in Dallas to spot the best blocks he could for us.

“We’d get 427 warranty jobs that we could make them four or five thousandths over. Those 348 cranks were 200-rod journals, and we could offset grind them and just about make any stroke we wanted; they were just the common GM, 1018 steel cranks. And they held up just fine at that level.”

It didn’t take long for word to get out about the boys from Arlington working on the big block combination, especially after they rolled out their first one – a 362-incher.

“Jenkins was nice about it and he wasn’t getting on me but just had to tell me, ‘You’re making a big mistake; there’s a lot of people been trying to run big blocks,” Reher said. “We were bound and determined to stick with the big block.”

As Reher saw it, the big block heads were the closest thing to the Ford; the one Glidden had been taking everyone’s lunch money for the last four years or so.

“We got this thing together and dialed it one Thursday night; we couldn’t believe how much power it made,” Reher admitted. “I mean that this can’t be we’re just like, something’s wrong with this thing. So we took that motor off and put the small block back on the dyno to see how it ran.”

After a few pulls, it became evident to them that the big block was not a mirage. It was the real deal. They took the Camaro with the big block out to a points race in Amarillo, Texas, and reset the record first time out, running an 8.35, 163.

After a few pulls, it became evident to them that the big block was not a mirage. It was the real deal. They took the Camaro with the big block out to a points race in Amarillo, Texas, and reset the record first time out, running an 8.35, 163.

Reher. Morrison and Shepherd had an interested party on the other end of the phone line to the tower.

“Glidden was calling all day long for updates,” Reher confirmed.

The big block hit the track at the NHRA Springnationals in Columbus, Ohio, and a rejuvenated Glidden scored a win at that event and did so, winning from the pole. In fact, Glidden made it two in a row, winning from the pole at the Mile High Nationals and beating Shepherd in the final round.

Shepherd made it interesting as Glidden qualified on top once again, as the tour entered July and the NHRA Summernationals in Englishtown, NJ. However, on race day, Shepherd drove to the win.

The one interesting scenario came in the first weekend of August when the NHRA Grandnationals outside of Montreal, Canada, rained out and was rescheduled the following weekend on top of the marquee NHRA Division 3 points meet then the Popular Hot Rodding Nationals at US 131 Dragway. Both Glidden and Shepherd were at the points meet on Friday to qualify, loaded up, and then drove all night for Saturday’s final eliminations in Canada.

Shepherd won Canada on Saturday, and they both returned to Michigan on Sunday, where Glidden notched the win. When Glidden fouled in the finals at Indy, it appeared Shepherd was a lock for the championship, inspiring NHRA top-end announcer Steve Evans to all but christen Shepherd as the champion.

However, following a controversial NHRA Fallnationals in Seattle, Wash., Glidden was declared the champion in a race where the ESPN coverage declared Shepherd the champion. Even though video evidence showed Shepherd with a substantial lead at the start and ahead at the finish line, NHRA reversed the decision and gave Glidden the win because apparently, the nose of Shepherd’s Camaro didn’t break the photocell beam. Even when NHRA was presented with the evidence, the decision stood.

However, following a controversial NHRA Fallnationals in Seattle, Wash., Glidden was declared the champion in a race where the ESPN coverage declared Shepherd the champion. Even though video evidence showed Shepherd with a substantial lead at the start and ahead at the finish line, NHRA reversed the decision and gave Glidden the win because apparently, the nose of Shepherd’s Camaro didn’t break the photocell beam. Even when NHRA was presented with the evidence, the decision stood.

It was still Shepherd’s championship to lose, and in the second round against Andy Mannarino, the Camaro rolled a sprag and did just that. Glidden went on to win, and both events of the event’s performance bests, which gave him the necessary points to pass Shepherd.

“We were devastated,” Reher admitted. “It was a crushing blow. We had a race that we could have won, and it wasn’t that we neglected anything. We did our maintenance and put in new sprags the night before. A brand new sprag rolled over.”

There was a lot of contemplating and determination on the ride home from Ontario, Ca.

“We were determined to come back faster and win every race we could,” Reher recalled.

“We were determined to come back faster and win every race we could,” Reher recalled.

They reached the finals in eight of 11 races, with Shepherd winning six.

They had their championship, and suddenly other details began to play into the equation. One of those details was adjusting the paint scheme to make the car photogenic.

“I think we were trying to make our business better,” Reher explained. “We wanted the car to be photographed well, and when we worked with the guy doing the graphics for the paint job, we said, because we’d looked at so many dragsters and the majority of them, couldn’t even read what it said on a car, in a picture. And that’s where we came up with the red, white, and blue and the black on white.”

Reher, Morrison and Shepherd branched outside their NHRA base when the series stopped requiring professional teams to race regional and divisional events. With the urging of Winston’s Jeff Byrd [and free hotel rooms], they made stops on the IHRA tour now that they could run their engines on a competitive basis with the original mountain motor cars.

‘It couldn’t worked out better,” Reher said. “So we’d leave an NHRA race, put the bigger motor in there. And it was like; you almost had to pinch yourself to think, is this even real?

‘It couldn’t worked out better,” Reher said. “So we’d leave an NHRA race, put the bigger motor in there. And it was like; you almost had to pinch yourself to think, is this even real?

Then there was the merchandising, which provided a sponsorship of its own. The IHRA allowed and encouraged shirt and merchandise sales right out of the back of the trailer. There was no split with the race series on sales either.

“We wouldn’t be the first ones at the track, but by the time we got to the track, there were always people waiting to buy a t-shirt; they were already standing by the trailer,” Reher recalled. “And that was a big blow when NHRA took that away, and you had to split it with them.

“As far as Pro Stock goes, I know that we sold the most. We’d gross about $15,000 a weekend. And they were marked up a hundred percent, so your net profit would be obviously half of that. Don’t you think that helped the racing budget?”

So yes, t-shirt sales funded most of their efforts on the track. In two full seasons, Reher & Morrison won 11 of 14 final rounds in the IHRA competition.

“I remember they were shorter races, and we didn’t show up there till Saturday morning, they had that one Friday qualifying session, but we’d go back to the shop and get as much done as we could,” Reher explained. “We’d take turns flying back to the shop. Wouldn’t bring the rig back.”

“I remember they were shorter races, and we didn’t show up there till Saturday morning, they had that one Friday qualifying session, but we’d go back to the shop and get as much done as we could,” Reher explained. “We’d take turns flying back to the shop. Wouldn’t bring the rig back.”

At $7,500 a pop to win a race and $10,000 for the spring race in Bristol, the team was handling the racing business very well.

In 1983 and 1984, Shepherd had the distinction of holding both NHRA and IHRA championship titles. In NHRA alone, he had compiled a career 173-47 win-loss record.

Earlier in their winning, Reher said they kept waiting for the shoe to drop, which never did. But that didn’t mean the competition wasn’t bridging the gap.

With 1985 on the horizon, the competition wasn’t the biggest threat to the team.

COMING SOON – PART THREE, TRAGEDY, TRIUMPH AND A LEGACY

DEADHEAD UNDER THE HELMET: JEG COUGHLIN JR.’S OTHER LIFE