PART ONE – 50 YEARS OF REHER-MORRISON – A GOLDEN ERA

PART TWO – 50 YEARS OF REHER-MORRISON – WINNING DEFINED

David Reher couldn’t believe what had transpired as he stood on the starting line at the Texas Motorplex. For the legendary Pro Stock engine builder, it was a bit of Deja vu.

David Reher couldn’t believe what had transpired as he stood on the starting line at the Texas Motorplex. For the legendary Pro Stock engine builder, it was a bit of Deja vu.

Twenty years after standing on the starting line while testing at a small drag strip in Ardmore, Oklahoma, Reher and business partner Buddy Morrison watched in horror as their driver and close friend Lee Shepherd was killed while making what should have been a routine pass.

Moments after what should have been a non-eventful qualifying run during the 2005 NHRA FallNationals, Allen’s Pontiac made an abrupt left turn toward the retaining wall just like Shepherd, except this time there was someone in the opposite lane. Kenny Koretsky had nowhere to go except through the middle of Allen’s errant race car.

Allen’s accident could have been another painful chapter during the previous 15 years where the revered championship trio was reduced to only Reher.

“That was a terrible thing to watch, and I couldn’t believe it was happening,” Reher said. “I couldn’t handle this happening again. I went down to the top end and almost didn’t want to go.”

Allen was alert, conscious, and talking to the medical personnel.

“That was a big sigh of relief,” Reher said.

But even before the accident, Reher admits, the team was already putting in motion their exit strategy from fielding a race team. Citing rising costs, among other reasons, the Reher & Morrison team was planning to get out of racing.

“We probably shouldn’t have started the 2005 season, but we did,” Reher admitted. “We had already discussed; we just didn’t have the money. We were getting older, and I know there were older people in the class, but we had to think about our future and what we were doing. The money had gotten to the point, and I don’t want people to take this the wrong way, but if I would have had the money, I would have spent it [racing]. “People came in there with money earned in different ways. You just don’t get rich building engines.

For Reher-Morrison, rich was a relative term, and their richness came in other ways.

CRACKS IN THE SIDEWALK

Headed into the 1985 season, Reher-Morrison-Shepherd was as solid as a freshly cured concrete patch. The team was now four-time champions and could have been five if not for some questionable decisions outside of their control.

Headed into the 1985 season, Reher-Morrison-Shepherd was as solid as a freshly cured concrete patch. The team was now four-time champions and could have been five if not for some questionable decisions outside of their control.

Reher-Morrison had been on a tear reaching the finals in 44 of 56 NHRA national events, winning 26. In 1982, when NHRA revised the Pro Stock division as a version of “mountain motor” Pro Stock racing and enabled more accessible crossover competition with IHRA, Reher-Morrison held dual championships for the 1983 and 1984 seasons. They won every race on the NHRA tour at least once, compiling a 173-47 record in NHRA competition alone. They won six of nine final rounds in two seasons with Shepherd on the IHRA tour.

While Reher-Morrison made winning look so effortlessly in 1981, 1982 and 1983, by 1984, the competition, including longtime nemesis Bob Glidden, Butch Leal and now Warren Johnson, were making those wins harder to come by. After a quarter-final loss to the resurgent Leal at the 1985 NHRA season-opener, Reher-Morrison, now sporting sponsorship from NASCAR giant Hendrick Motorsports, knew they would face a monumental challenge if they wanted to win a fifth consecutive NHRA title. They had just learned some new data through their association with Bruce Allen who was working at McLaren at the time, and were eager to implement it.

As the team prepared for the NHRA Gatornationals, they worked in a test session in Ardmore, Oklahoma, one of their traditional testing venues. As Reher put it, “It was just another test session.”

But the weather wasn’t so normal. While the temperature for the day was recorded as an average of 69 degrees, the wind gusts of up to 23 miles per hour made a difference. In those days, it wasn’t uncommon for an NHRA event to proceed with similar or higher wind gusts.

On the fateful pass, Shepherd launched and pulled the parachutes when the car went out of control, veered left, and then right before the car went into a series of rolls

The car was destroyed except for the roll cage, which remained intact following the accident.

“I was in total shock and still have emotions about that [day],” Reher said. “It’s something you think will never happen to you. But I guess it does happen.”

At the 1985 NHRA Gatornationals, the event Shepherd was preparing for, race officials staged a remembrance with the 16-car field, with a missing man formation and a moment of silence.

Devastation seemed inadequate to describe Shepherd’s death’s effect on Reher-Morrison and the drag racing world. Racers in competition immediately put a black slash through the permanent number on their race cars.

THE AFTERMATH

If Reher understood one thing about his fallen friend, he knew Shepherd’s love for the team and the sport would want the team to continue chasing Pro Stock supremacy.

If Reher understood one thing about his fallen friend, he knew Shepherd’s love for the team and the sport would want the team to continue chasing Pro Stock supremacy.

“We knew he would have wanted us to go on,” Reher said. “I knew it wouldn’t have been healthy for us [me and Buddy] to quit.”

While Reher understood there could never be a replacement for Shepherd, there could be a successor. There was no doubt who could fill this role.

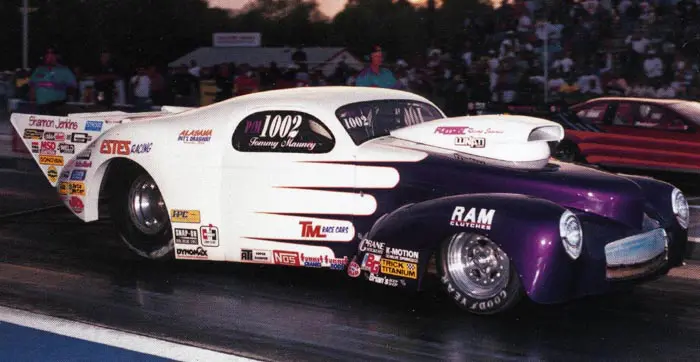

Bruce Allen, who had been a sportsman standout and made the transition to Pro Stock, was Reher-Morrison’s man. He had help them make significant tech gains through his association with the V-6 Buick program at McClaren.

Allen transitioned from Competition Eliminator to Pro Stock by purchasing with then partner Jim Hanley the Reher-Morrison championship-winning 1981 Camaro. He had accompanied the team to some events and spent much of his time observing Shepherd’s approach.

“He took on a tough job,” Reher said. “We had a lot of calls from people who wanted to drive the car. Bruce wasn’t looking for the job; we asked him to drive.”

Reher-Morrison and the drag racing community weren’t the only ones devastated by Shepherd’s passing. Allen was too.

“You never think that things like that will happen to someone you know,” Allen admitted. “One of the hardest things was seeing how it affected Buddy and Dave. I didn’t know them anywhere like I do now. Before I knew what had happened to Lee, I was already in Gainesville, preparing for my first Pro Stock race.

“That tore my heart out. My idol and the person I looked up to was gone. And even though we knew that could happen to anyone at any time, it still is emotional.”

“That tore my heart out. My idol and the person I looked up to was gone. And even though we knew that could happen to anyone at any time, it still is emotional.”

Allen said he would have never applied for the job, and it took Reher-Morrison’s invitation before he would have considered driving for them.

“I was not worthy of it,” Allen admitted. “I had no experience to speak of. They had won four NHRA championships and another two IHRA; knowing what kind of shoes that was to fill, I knew that I was not worthy of that position. I never dreamed in my wildest dreams they’d ask me.

“When they did ask me, the reality was I was sure if I wanted to do it like that. It would have been a lot easier if Lee had retired. At least I would have had my mentor there to help me. It was a gut check whether this was something I wanted to do.”

By late April, Reher and Morrison began making their way back to the drag strip and were seen helping Allen with their former car. Allen had maintained racing, and just before the IHRA Spring Nationals, Reher-Morrison announced their return with Allen as their driver.

Allen made a stout first impression by driving his way to the IHRA win in Bristol; then, in his NHRA debut at the Cajun Nationals, he drove to the No. 1 qualifying position. Allen drove his way to the final round at the NHRA Springnationals in Columbus and later the victory at the NHRA Grandnational in Montreal. He also won four of seven final rounds to clinch the IHRA championship.

Allen won three national events in his debut season. He won 11 more in the 1990s, but little did the team realize there would be another dark shadow looming on the horizon.

THE OTHER SHOE DROPS

Noted drag racing journalist Rick Voegelin best described Reher’s longtime partner Morrison as an outside-the-box thinker.

Noted drag racing journalist Rick Voegelin best described Reher’s longtime partner Morrison as an outside-the-box thinker.

“You could have a conversation with Buddy about Zen philosophy, which is not something you would normally do with a drag racing buddy,” Voegelin said. “I think that Buddy was the one who made them push the limits. He was the one who was always, ‘Well, why don’t we try this, or why don’t we do that?”

“David, by nature, is a very conservative person whereas Buddy would be more outgoing. He was sort of the outgoing face of Reher-Morrison.”

They were an incredible trio, between Shepherd’s keen ability to feel a car through the seat of his pants and Reher’s ability to see everything in slow motion before the technology was readily available. Morrison always brought in the big ideas like building a bigger shop and others that made an impact on the team. They all had a method of working and not stepping on each others toes.

Then, in May of 1996, the team, now with Allen, was dealt another blow. Morrison was diagnosed with cancer.

This time with Morrison, Reher got to say his goodbyes and prepare for the inevitable, unlike Shepherd when there was no warning.

“As I get older, I think about it more. Those were two different kind of deals,” Reher said. “Lee was an unbelievable shock that I wasn’t prepared for in any way. Obviously just devastating. And Buddy’s deal was something that we knew was happening. The last six months of his life were tough to watch a friend go through.”

Though Allen was relatively the new face on the block, in his time with Morrison, Buddy left an indelible mark.

“Buddy was one of those guys that was a true friend to everyone that ever met him,” Allen said. “I was always impressed with his ability to inspire the people around him. He was always forging ahead and looking for the next ‘new’ way to do something. People like Buddy are the very reason our sport exists. It’s that optimistic ‘Let’s try this’-attitude that Buddy always exhibited, which spurs us all to push our cars to the edge of technology. Buddy truly had vision.

As Allen sees it, Morrison was irreplaceable.

Reher agreed, and he and Allen finished up the 2005 season and rode off into the sunset with their race team. Instead, they focused on the engine shop and made many moves in the Pro Modified, fast doorslammer, and bracket racing world.

WINDING DOWN

Reher learned that when you have a successful business model, the demand rarely wanes and such has been the case for Reher-Morrison.

Reher learned that when you have a successful business model, the demand rarely wanes and such has been the case for Reher-Morrison.

“We really have a good group of employees,” Reher said. “They have kept us going. And part of the reason I’m here right now is, I guess there’s several of us don’t even know anything else to do. We’ve scaled back. I told Bruce we’ll quit advertising it and maybe this thing will just kind of fade out. Well, that hasn’t happened.

“We just keep getting orders. We got more than we can do right now and we’re going to get it done. We tell them the wait times and they still keep coming which is a testament to what we have built here.”

Recently Reher came face-to-face with his own mortality.

Last October, just as the NHRA was prepared to come to Dallas for the FallNationals, Reher began feeling down on power.

“I told my wife I didn’t feel very good and then all of a sudden, in the middle of the night, I just had this incredible pain,” Reher explained. “It was unbearable. I’d never felt anything like it ever. One time I punctured the lung and broke five ribs and nothing was compared to that. And I said, ‘We have got to go right now.”

Reher’s insistance on visiting the hospital might have very well saved his life.

“They said I was lucky to come right in,” Reher admitted.

Within hours, Reher was in surgery to remove a blockage in his small intestine that had become infected. Doctors removed five feet of his infected intestine.

“They didn’t want me to wake up between surgeries so they had me on a ventilator for five days and knocked out,” Reher said. “There’s probably a good 10 days I don’t remember anything about. Half of that time I was out of it. And then when they started bringing me to, I still don’t remember that. Then when I got in intensive care, I started coming around and the nurses were real good and they did a real good job of taking care of me.”

Reher counts his blessings to still be alive at 72, and still comes in the shop daily.

“People ask me, ‘why don’t you retire?” Reher said. “I say, ‘Well, I don’t know how to retire.”

“Now, who’s really working hard here as far as machining is Bruce Allen. He does a lot and he leaves the running the place up to me. He stepped up to the plate when I was out for seven weeks. So he’s a big part of this deal.”

Reher said the customers and fans have been a big part of the Reher-Morrison legacy, and one he feels blessed to have experienced.

“I’ve been a very lucky man, to do what you passionately loved and what you wanted to do from being a little kid in grade school and in high school and reading, having your hot rider car craft magazine inside your notebook and getting busted by the teachers because you were reading it during class,” Reher said. “So I lived a life of doing what I always wanted to do. That’s not to say it’s all been fun and games, but I’d say I’m luckier than most.

“We were just three guys who had a passion for racing, and not unlike anyone else who followed their dreams. Fortunately we had enough education to make things work. It wasn’t throwing stuff at the wall and hoping it stuck. We just figured out how to do stuff. Bruce was a very important part of this as well and did so in a tough situation.

“We all made it work. It was a rewarding experience of a lifetime.”