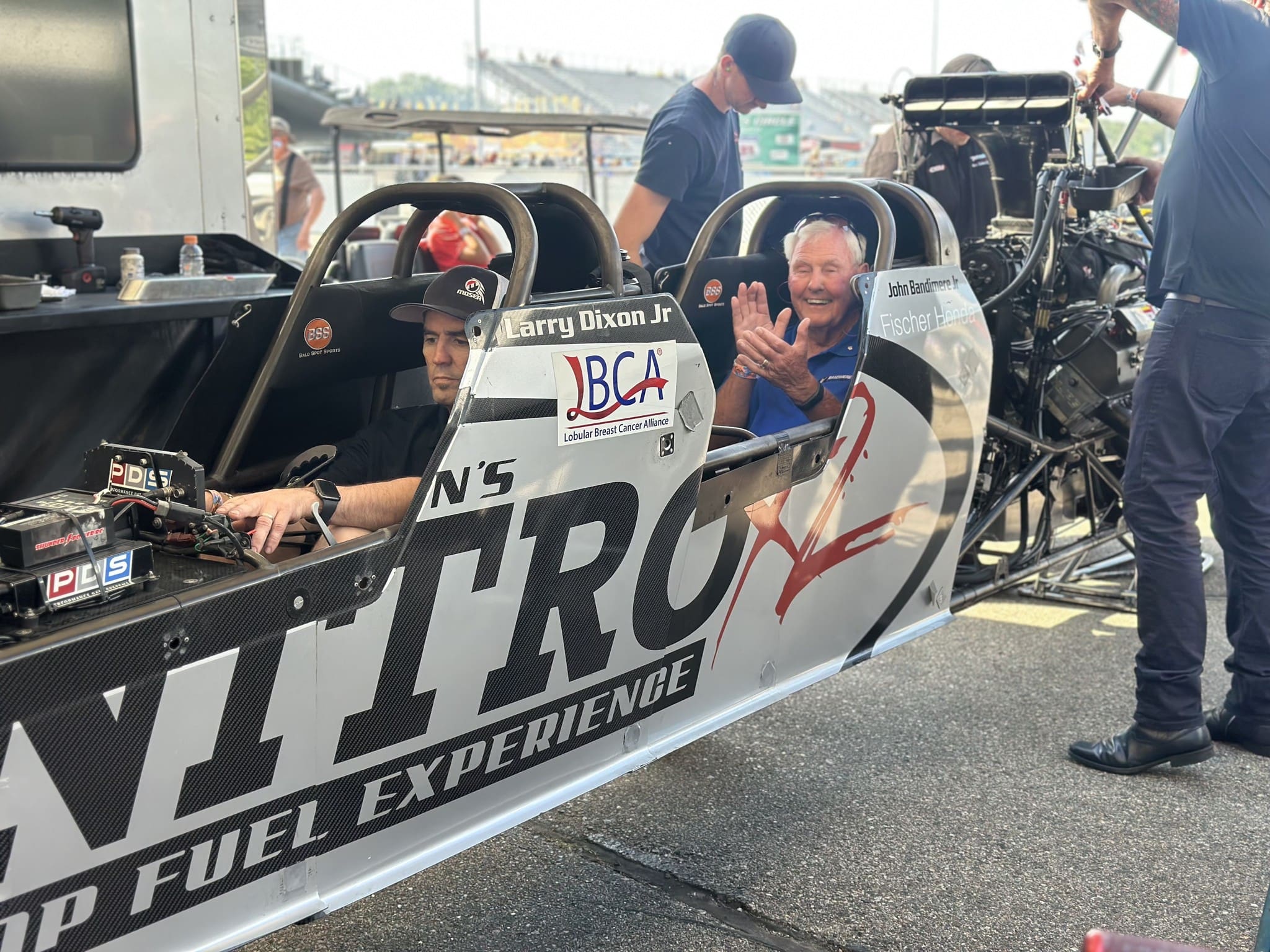

For decades, John Bandimere Jr. stood just beyond the guardrails of the dragstrip he helped make famous, promoting the thunderous spectacle of Top Fuel drag racing at Bandimere Speedway. But until recently, he never truly understood what 11,000 horsepower felt like until he strapped into Larry Dixon’s two-seat Top Fuel dragster.

At 87 years old, Bandimere took his first ride down the eighth-mile in a nitro-powered machine at the PDRA Northern Nationals, an experience he said brought him closer to heaven than almost anything else.

“It was… When he did the burnout, the car kind of felt like it was floating,” Bandimere said. “And then I was really surprised when Larry hit the brakes because those cars really stopped fast.”

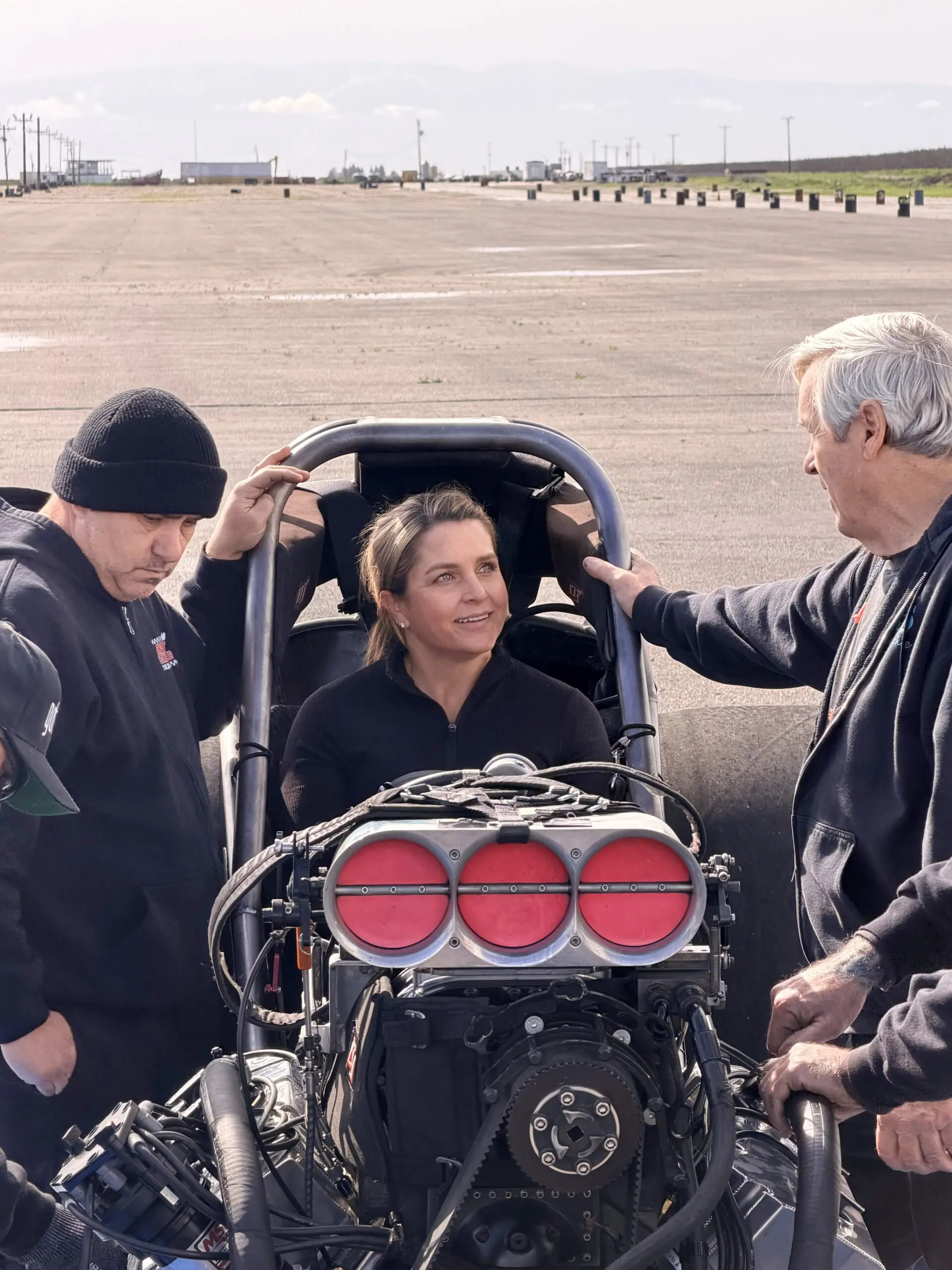

Dixon, a three-time NHRA Top Fuel world champion, created the two-seat dragster to give people a rare opportunity to experience the violent acceleration of a Top Fuel car firsthand. At $12,500 a ride, it’s a pricey ticket—but one Bandimere didn’t have to cover, thanks to his daughter Tami, who arranged the experience as a gift.

Bandimere, still sharp and energetic, was amazed by what he saw and felt from the passenger seat. He said when Dixon staged the car and launched, everything became a blur of power and motion.

“The feeling of acceleration was just amazing,” Bandimere said. “I asked him, ‘How many runs does it take before things slow down?’ He said it’s different for everyone, but even for guys like him, if they’ve been out of the car a while, it feels fast all over again.”

That sensation, Dixon explained, eventually slows to a level of awareness where small details—like spotting a Dzus fastener on the racing surface—become visible. For Bandimere, that revelation underscored the incredible mental focus required to drive these machines.

Bandimere is no stranger to speed. He once attended the Frank Hawley Drag Racing School and has driven his own fast door cars. But none of that, he said, compared to what he experienced with Dixon.

“When I was in there, they got me tied in pretty good with gloves and everything. I’m thinking to myself, ‘I’m glad I’m not claustrophobic,’” Bandimere said. “If I was, I’d have had to get out of that car right then.”

Before the ride, Bandimere endured a 45-minute delay when a door car crashed during the run group before him. The wait, he admitted, gave him too much time to think about what he was about to do.

“I’ve seen thousands of Top Fuel cars go down the racetrack and spin the tires, go sideways, all of that,” he said. “When you sit there for that long, strapped in, it gives you a lot of time to think.”

The pre-run ritual was an experience in itself. Dixon invited Bandimere to climb in during engine warmup, following a tradition passed down from Dixon’s former tuner, the late Dick LaHaie. LaHaie insisted on stabbing the throttle during warmup to help seat the clutch, a jarring moment Bandimere won’t forget.

“When he hit that throttle and we’re in the car, that was an amazing feeling,” he said. “Just that ‘Wah!’—you feel every bit of that horsepower.”

Once in the trailer, the full preparation began. Dixon outfitted Bandimere in full fireproof gear—socks, boots, gloves, and a five-layer suit. The snug fit and awkward boots made it difficult to move, let alone think about emergency exit drills.

“To get out of one of those cars, you really have to practice,” he said. “I started to wonder—if something had gone wrong, could I have gotten out in time? I don’t think I could have. That gave me a new appreciation for what these guys go through.”

Bandimere’s awe only grew after the parachutes deployed and the car slowed to a halt.

“I was just in awe of how fast everything takes place,” he said. “In my heart, I was crying tears of joy just from the standpoint of having the opportunity to experience that.”

His emotions poured out at the finish line.

“I was hollering, ‘We made it! We made it! We made it!’” he said. “I was so thankful to the Lord for a safe ride.”

Would he do it again?

“They asked me, and I said, ‘I’d do it 10 or 15 more times,’” Bandimere said. “That’s why I asked Larry, ‘How long does it take before things slow down?’ Because if it takes four or five more runs, I’d like to do those just to really enjoy the experience.”

Holding onto the steering wheel for dear life, he wasn’t about to wave to the crowd, but his mind was already thinking about another pass.

“I was holding on to that steering wheel for everything I had,” he said.

The experience gave Bandimere not only a thrill but also a deeper understanding of why Top Fuel drivers are so passionate about what they do. He recalled a story Dixon shared with him—one that stayed with him more than the speed.

After giving a ride to Burnell Russell, father of the late Top Fuel driver Darrell Russell, Dixon said Burnell sat quietly in the cockpit for an extended time, not wanting to leave.

“He said, ‘Now I know why my son loved doing this,’” Bandimere recalled. “When I got out of that car, I understood exactly how Burnell felt.”

Darrell Russell was killed in a racing accident in 2004 at Gateway International Raceway. For Burnell, the experience connected him to his son in a way he hadn’t before. For Bandimere, it was a reminder of the risks and rewards of the sport he’s spent his life promoting.

“I have so much more respect now for those guys who climb in every weekend and do this,” Bandimere said. “It’s something I’ll never forget.”

Though Bandimere no longer oversees day-to-day operations at Bandimere Speedway, which closed at the end of 2023 after nearly 65 years in operation, his legacy in drag racing is cemented. And with one unforgettable run down the track, he now carries not just the promoter’s perspective—but the racer’s.