A LAST STAND FOR THE CHI-TOWN HUSTLER - THE CHAMPIONSHIP YEARS

Originally published May 2007

From Match Race Monster to World Champion - How Frank Hawley and Chi-Town Hustler Stomped the NHRA's Best in 1982

The old racing cliché goes, Speed costs money – how fast do you want to go?

The old racing cliché goes, Speed costs money – how fast do you want to go?

That’s true more than ever in this day of highly professional drag racing with its mega-dollar sponsorships. A financial underdog who rises up and challenges the big names, even for just one national event, causes wonder and amazement - witness the attention given to Top Fuel pilot Joe Hartley’s runner-up spot at Houston earlier this season.

Now imagine such a team, living race-to-race, taking on a full season of NHRA national events against a combination of proven dynasties and fast-rising stars, all fully sponsored – and winning a world championship.

That may never happen today. But it did 41 years ago, when a team that made its name at the dawn of Funny Cars added the NHRA trail to its guaranteed-money match race schedule for the first time in its legendary history and defeated the giants of the sport.

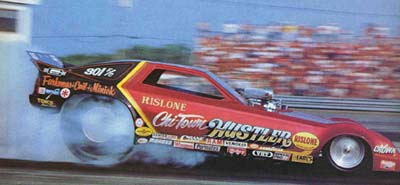

In 1982, the Chi-Town Hustler – crew chief Austin Coil, manager/part-owner Pat Minick, driver Frank Hawley and crew members Wayne Minick and Larry Walinek – took the NHRA Funny Car Winston Championship, running wherever someone would foot the bill and beating the likes of Don Prudhomme, Raymond Beadle, Kenny Bernstein, Billy Meyer and almost everyone else they faced.

Beadle had the Funny Car world by the throat at the time, winning three straight championships from 1979-81, while Prudhomme had taken the crown the four years before that. Bernstein would go on to win four straight titles from 1985-88.

“For an outsider to come in and do as well as they did capture everyone’s attention,” said Dave McClelland, once the host of Diamond P Productions’ syndicated NHRA TV shows. “It was a thrill to watch guys like the Chi-Town Hustler group come in to a cadre of cars that dominated the circuit. The class was dominated by three cars for about 10 years, and that’s what made (the championship run) such an outstanding achievement.”

“For an outsider to come in and do as well as they did capture everyone’s attention,” said Dave McClelland, once the host of Diamond P Productions’ syndicated NHRA TV shows. “It was a thrill to watch guys like the Chi-Town Hustler group come in to a cadre of cars that dominated the circuit. The class was dominated by three cars for about 10 years, and that’s what made (the championship run) such an outstanding achievement.”

And the Hustler crew did so on a budget that was a fraction of Beadle’s Blue Max, Bernstein’s Budweiser King, Prudhomme’s Pepsi Challenger or Meyer’s Chief Auto Parts/7-Eleven cars, dragging their Dodge Charger across the country on a 1967 crew cab ramp truck, its odometer well past the 1 million-mile mark, while the other professionals hauled around with fully enclosed tractor-trailer rigs that were just coming into vogue as both useful and rolling billboards. Of course, there were just 10 NHRA national events then, but match races meant professional teams had little down time.

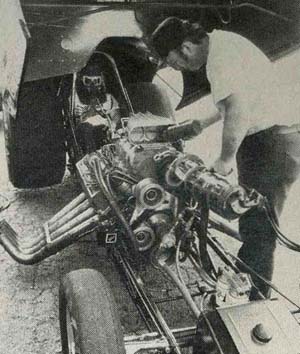

“We had a total gross budget for the year of $300,000,” Coil said back in 2007. “Twenty-five-thousand dollars was sponsor money, and the rest was in match race winnings and round money. Our annual payroll alone now is about $4 million (at John Force Racing). We hauled with that straight truck; they had semis. They had 6-8 spare motors; we had one. We never ran on borrowed money – if we didn’t have it, we wouldn’t go.”

While the Chi-Town championship may have been a surprise from a budgetary standpoint, it wasn’t an upset to the teams who raced against them for years on the hired-in circuit.

“It didn’t surprise me they won,” Prudhomme said. “A lot of guys on the touring circuit didn’t realize how sharp Austin was, but those of us who ran the match races for years, myself, Beadle, (we) knew what they could do.”

“When we first went, the NHRA guys made it sound like we came out of the woodwork,” Minick said. “The NHRA hierarchy … knew who we were, but never gave us credit for doing what we did. But all the racers knew who we were.”

SURVIVING A CHANGING MATCH-RACE WORLD

At the time, the world of professional racing was in transition. In the 70s, some F/C teams made a living by running for guaranteed money several times a week at strips all across the country.

At the time, the world of professional racing was in transition. In the 70s, some F/C teams made a living by running for guaranteed money several times a week at strips all across the country.

But, the early 80s saw the match race circuit fading out as national events took on increased significance, especially given NHRA’s TV deal. And, a new wave of drag racing fans might not have known the exploits of Farkonas, Coil and Minick (John Farkonas, an engineer, was no longer involved with the car on a day-to-day basis, but his name remained on its flanks) as the Hustler’s earth-shaking burnouts and fast times on marginal strips made it one of the most feared Funny Cars of the 60s and 70s.

“The match race trail was drying up,” Coil said. “The Chi-Town Hustler was always totally funded by match racing. We made a living off it from 1969 to 1984. We ran the occasional national event, but until the early 80s, we didn’t need to. We had to move into NHRA and get exposure, or we were gonna fold.”

Coil added he was also unhappy with how NHRA handled the floppers in previous years, based on the team’s occasional experiences at national events.

“NHRA was not attractive for us,” he said. “They treated some of us like we were G/Stock Automatics; you didn’t have qualifying organized, so you had to sit in line all day just to make a run. We just decided we were never gonna do that.”

Minick, who booked sponsors and hired-in appearances, partially agreed, although he noted the team hit the NHRA trail because it put together enough money to get to the races, per the Hustler credo. He added that the team didn’t make every national event that year, but made some hired-in events that just happened to carry an NHRA sanction and awarded half points, such as the Popular Hot Rodding Magazine Championships, then one of the most prestigious booked-in races, which Hawley won.

Minick, who booked sponsors and hired-in appearances, partially agreed, although he noted the team hit the NHRA trail because it put together enough money to get to the races, per the Hustler credo. He added that the team didn’t make every national event that year, but made some hired-in events that just happened to carry an NHRA sanction and awarded half points, such as the Popular Hot Rodding Magazine Championships, then one of the most prestigious booked-in races, which Hawley won.

“The whole picture was changing,” Minick said. “TV was coming in, and…until TV, national events were not as lucrative. Look at (Top Fuel racer) Jeb Allen - he won the NHRA championship (in 1981), won an IHRA championship, and a couple years later, he was broke. I swore until it made economic sense to go NHRA racing, we couldn’t afford to do it. I think it’s somehow demeaning as professional racers to pay to go race; it’d be like Bob Hope paying at the gate to get into his show.”

He also takes exception to the term “match racer” when describing the Hustler, pointing out the team ran numerous 8-to-32 car events with Prudhomme, Beadle and other national event hitters in those fields, such as the Pop Hot Rod show.

“The term ‘match race’ is very misleading,” Minick said from his suburban Chicago home. “To me, that sounds like you’re racing different types of cars in insignificant events. I would call them ‘featured car events.’ When we’d go to one of them so-called insignificant races, it was just as tough as a national event.”

Minick said he doesn’t recall making a “We’re chasing the championship” commitment that year, although he said, “We were confident enough to know that given the chance, we could go a long way.”

Neither do Hawley or Coil recall a definite commitment, although Coil said having Hawley behind the wheel influenced his thinking about the national event trail.

Neither do Hawley or Coil recall a definite commitment, although Coil said having Hawley behind the wheel influenced his thinking about the national event trail.

“That was kind of in our plans from the very beginning with Frank,” Coil said. “If it ever worked out where Frank was running good enough to compete, we’d give it a shot.”

Hawley came on board in 1980 after running a family-owned front-motored fueler, BB/Funny Car and alky altered on the Midwest’s tough United Drag Racers Association (UDRA) circuit and winning one championship. When the Chi-Town seat opened up after the 1979 season, fellow BB/FC pilots Simon Menzies and Al DaPozzo recommended Hawley as a driver with potential. So Hawley sent Minick his resume and got the job.

“At the end of '79, I was trying to move up,” Hawley said from his Florida racing school, “and I heard Pete Williams had quit (driving the Hustler). Menzies said to me, ‘Why don’t you send them a resume?’ It was probably a little unusual, but I thought it would be a little more professional.”

“Frank as willing to drive for really cheap,” Coil said with a chuckle. “He was known to us from the UDRA circuit, showed some talent in his alky cars. Some mutual friends talked us into giving him the ride.”

Hawley said the team stuck mostly to the match race trail in his 1980 debut season, with a couple of IHRA races thrown in, as he learned how to be part of a pro fuel team.

Hawley said the team stuck mostly to the match race trail in his 1980 debut season, with a couple of IHRA races thrown in, as he learned how to be part of a pro fuel team.

“It was tough,” he said. “We didn’t have a very big crew. I drove, did the bottom end and clutch, drove the truck sometimes, although Austin didn’t much like the way I drove it. It was nonstop work.”

Nineteen eighty-one brought fast times and wins at some 8-car shows. Hawley said a turning point came at that year’s NHRA Summernationals at Englishtown, N.J.

“We did pretty well there (qualified eighth and advanced to the second round), and we knew we were as fast as Prudhomme, Beadle, Meyer, everyone else,” Hawley said. “We just weren’t going to the races they were.”

And while Coil was long known for his ability to tune the Hustler to get down tracks with less-than-perfect traction, Hawley was also learning how to get down those tracks. Most notably, he was using the old-school method of pedaling the accelerator and pulling the brake to hook the car up, while almost everyone else either tried to drive through their tire shake or used the clutch pedal.

“That’s the way I learned to drive it,” said Minick, the Hustler’s original pilot. “(Pedaling and using the brake) was becoming a lost art at the time. Frank didn’t even realize you were able to do that.”

“That’s really not a bad training ground,” Hawley said, “to be in places where things aren’t perfect. Driving down a short, dark, slippery track was something I’d done all my life, so when I went to my first NHRA track, I was in heaven!”

Hawley also learned to keep the car between the guardrails. Unfairly or not, he had a reputation as a crasher, and in what today’s educators would call “negative reinforcement,” Coil told Hawley he had sawed halfway through the roll cage bars and filled them with lead filler. Coil hadn’t, of course, but Hawley wasn’t about to put it to a track test.

“The idea of crashing the car was something I couldn’t accept,” Coil said. “(The car) was our business.”

“I never did hit anything with the car,” Hawley said.

DOMINATING, AND GOING (ALMOST) BROKE

Thus, the Hustler was primed for that 1982 season. Armed with a new, lighter, more aerodynamic Charger body to replace the old Challenger and new aluminum cylinder heads, the team headed to an 10-car show at Orange County International Raceway a week before the NHRA Winternationals.

Thus, the Hustler was primed for that 1982 season. Armed with a new, lighter, more aerodynamic Charger body to replace the old Challenger and new aluminum cylinder heads, the team headed to an 10-car show at Orange County International Raceway a week before the NHRA Winternationals.

“We had a few match race dates that paid for us to go to Pomona,” Coil said, “We didn’t have pre-season testing back then, so Orange County was like everyone’s pre-season test. Now it’s insane – we pay to test.”

Not only did the Hustler win the OCIR opener, it did so with a string of low 6.10s, more than four-tenths ahead of its nearest competitors. Then, at Pomona for the Winternationals, Hawley took the Chi-Town to a low-qualifying 5.861, .001 off Bernstein’s national record, and went to the semifinals, where Beadle hung a holeshot on Hawley for a 5.97 to 5.96 win.

From there, the team went to Gainesville for the Gatornationals, the second stop on the NHRA tour. There, Hawley qualified second to Beadle, the only two cars in the fives on a tricky track, and won the Hustler’s first-ever NHRA national event with a string of 6.0s, putting the Hustler atop the points standings.

“The way I understand it, we hadn’t decided to go to Gainesville until we were on the way home form Pomona,” Hawley said. “Then, after we won, we decided well, we might as well go to Atlanta (where Hawley runner-upped to Beadle in the NHRA Southern Nationals). Had we done poorly early on, I don’t think there would have been any Chi-Town Hustler world championship.”

“Gainesville kinda set the stage for us to keep trying,” Coil said. “I don’t recall anything special we did that year (to the car). We were just consistent.”

Many expressed surprise at the Chi-Town’s fast start to the season, and the Diamond P telecasts began playing up the David-versus-Goliath scenario developing around the team and its blue-collar, old-school fan base.

“They had a huge reputation in the match race world, but there were huge question marks as to what they could do in open competition,” McClelland said. “I assure you some people were skeptics … said, ‘Sure, they’ll do great burnouts, but …’ A month before (the season started), if you asked who would win, nobody would have said the Chi-Town Hustler.”

“Matter of fact, we were surprised NHRA was surprised (at the fast start),” Minick said. “When our car went to the line, there was the best possible stuff put on it. It didn’t come in a tractor-trailer, but I guarantee you it was the baddest Jose on the planet.”

“I remember (broadcaster) Steve Evans playing it up as much as he possibly could,” Hawley said. “He’d show the other teams with their 18-wheelers and big crews, then come over to our guys and the ramp truck.”

The Hustler stayed near or on top of the points all season, winning the Springnationals at Columbus, briefly losing the lead mid-summer, then winning the aforementioned Pop Hot Rod event and the inaugural NorthStar Nationals at Brainerd to get back out front as the chase headed into the homestretch. Prudhomme and Meyer suddenly began putting up record times and speeds in hot pursuit.

The Hustler stayed near or on top of the points all season, winning the Springnationals at Columbus, briefly losing the lead mid-summer, then winning the aforementioned Pop Hot Rod event and the inaugural NorthStar Nationals at Brainerd to get back out front as the chase headed into the homestretch. Prudhomme and Meyer suddenly began putting up record times and speeds in hot pursuit.

“They had found a way to burn huge amounts of nitro,” Minick said. “But they kept blowing up, too. At Indy, Prudhomme was wasting an engine a run. We had a complete block on the truck and enough parts to build another. We couldn’t afford to keep throwing parts at it. At Brainerd, we were looking at the engine in the car, and it was getting tired, so we decided to put the spare in. It was in the truck so long, it had cobwebs. We blew them off, cleaned it up – and set low ET and won.”

Hawley and Coil recall the debut of the Big Bud Shootout at the U.S. Nationals as a defining moment in the Chi-Town season – Hawley, because he beat Prudhomme in the final, and Coil, because he says the $25,000 winner’s check enabled the team to finish the season.

“When we left to go to Indy, we were broke,” Coil said. “During the season, we had match race dates, but as the season was drawing to a close, the match races were winding down. I wanted to give (the points race) a shot, but if we came home without any money, we weren’t going to California (for the last two national events).”

“Well, that’s one of those things a manager says to the employees sometimes, to keep them hungry,” Minick said. “We bordered on (shutting down the points chase), but I was confident if push came to shove, we’d somehow find the money to keep going, could have wheeled and dealed to find a sponsor.”

The Bud Shootout check erased any doubts. But Hawley exited Indy in the first round, and although Prudhomme ran a jaw-dropping 5.63 at Indy, Meyer became the closest competition in the points by winning the event.

The chase came down to the World Finals at OCIR. Hawley was eliminated in the semis by Tripp Shumake – in a second Meyer car – but Meyer also lost in the semis, giving the Hustler the championship.

While Hawley admits to being excited after it was over, Coil and Minick apparently looked at their championship more practically.

“Frank, I think, was just overwhelmed by it all,” Minick said. “Austin and I were more seasoned veterans. We appreciated it from the point of the business.”

“Obviously, I was happy,” Coil said. “The bonus check ($30,000) was chicken feed compared to the bonus today. I just thought, ‘OK, we got the money; I can get a new blower, cylinder heads. And everyone got a bonus. In that era, it didn’t mean much. The only thing it did is, now we could get $5,000 for a match race date when we were getting $2,500 before.”

Coil said some sponsors approached the team about jumping aboard the Hustler bandwagon, but nothing of note came of those. The Rislone name adorned the Hustler in 1982, as it had for years, but the additive firm was not a big-money sponsor. Minick said the inability to get a big sponsor out of the championship is one “what if” he takes from the season.

“Yeah, we made a mistake there,” Minick said. “We were perceived as something less than the caliber it took to do that. I always thought you were judged by your accomplishments, not your appearance. But the whole thing about having the open trailer, for example – to the people, that was cute. To a sponsor, no.

“We never were really able to get a big-time sponsor,” he continued. “It takes money to make money, I know. But if we had to buy a drum of nitro or go to New York to wine and dine some corporation, we’d buy the nitro. We wanted to race.”

EPILOGUE

As it turned out, low-budget lightning can strike twice in the same place.

As it turned out, low-budget lightning can strike twice in the same place.

When 1983 rolled around, the Chi-Town gang was back on the NHRA trail and picked up a sponsor midseason. Bob Stange’s Strange Engineering started a “super team” with the Chi-Town, fellow Chicago racers Chris Karamesines and Fred Mandoline (who won the ’83 Pro Comp title in his BB/FC), the Pro Stock team of Don Coonce and Albert Clark and others in the sportsman ranks.

“Team Strange was a bunch of flash and show,” Coil said when asked how lucrative the deal was. “He said he had a few bucks to give us, and at that time, every $1,000 was heaven.”

The Hustler was even more dominant that year, winning the first three nationals, adding a fourth that summer at Denver and wrapping up a second straight points title well before the season ended.

“Same chassis, different paint,” Minick said. “We didn’t join in the big nitro volume, parts-crushing stuff like everyone else.”

But 1984 saw the Hustler blanked in the NHRA win column, and changes started coming. Hawley left to start his then-innovative drag racing school in Gainesville, Fla., later stepping into the cockpit of Darrell Gwynn’s Top Fuelr car after hiss devastating crash in England to win two more NHRA national events in 1990.

“I stayed with Austin five years,” Hawley said. “Austin told me he had something like five or six hundred drivers, and nobody other than me lasted more than two years. You can say that’s a compliment, or I’m that submissive. I think probably it took two-and-a-half years before Austin ever gave me a compliment. For sure it wasn’t in the first two years. But our relationship ended up good.”

“I stayed with Austin five years,” Hawley said. “Austin told me he had something like five or six hundred drivers, and nobody other than me lasted more than two years. You can say that’s a compliment, or I’m that submissive. I think probably it took two-and-a-half years before Austin ever gave me a compliment. For sure it wasn’t in the first two years. But our relationship ended up good.”

“Frank seemed to struggle to be first off the line,” Coil said. “But he made up for it with his feel for getting the car down the track.”

“Hawley was pretty optimistic about what his abilities were,” Minick said with a chuckle. “(But) it had been a long time since we had someone of his ability in the car, someone who could work the controls like he could.”

And the almost unthinkable happened as Coil left the Hustler to work for an emerging flopper pilot named John Force.

“We were real happy we did good those couple of years,” Coil said. “My position here (with Force) came out of it, and I doubt if Hawley would’ve been able to put together enough investors to create his drag school.”

“Austin is the guy that won us the championships,” Hawley said. “I’m a big believer in his ability.”

“I’m proud of Austin, to be able to withstand what it took to (win the championships),” Minick said. “He proved to be good enough to get the job done, plus plus.”

Minick’s son, Wayne, took over driving duties of the Hustler, and Walinek became the new crew chief. And there was another new member on the team.

Minick’s son, Wayne, took over driving duties of the Hustler, and Walinek became the new crew chief. And there was another new member on the team.

“We still had the same truck,” Pat Minick said. “But once Austin left, they refused to ride in it anymore.”

The team stuck to the featured car circuit for “four or five years,” Minick said, before shutting down.

“I didn’t want to beat up and down the road anymore,” he said.

But the Hustler may live on again. Minick recently found the famed 1969 Chi-Town Charger that terrorized the country, sold it to someone who commissioned him to rebuild it the right way and is now building a duplicate because the original is “too nice to race” on the nostalgia circuit, he said.

So while a Chi-Town Hustler may hit the nostalgia tour and wow fans with loud, long burnouts, it won’t duplicate the heroics of a different version 25 years ago. Nor is any other contemporary team likely to.

“Twenty-five years ago, it was possible to work your way up the ladder with enough talent and desire,” Coil said. “Back then, somebody could go into the garage, cast their own set of pistons and go out and set a record (as the Hustler did with a set of Farkonas-designed pistons in 1970). Now you gotta have good funding and facilities, or it’s not gonna happen. We used to run with three guys on the car. Now, the work level’s about quadrupled. You can’t do it any more unless you have a really wealthy daddy.”

“It staggers my mind when I look back on it,” McClelland said. “It was a magical time.”