Once IHRA joined the fray, drag racing’s sanctioning-body wars turned into a three-way brawl. Fans saw it as a golden era – three logos on posters, three points chases to follow and three sets of rulebooks trying to buy their loyalty.

Behind the scenes, it was far nastier. Carrier clashed with Parks first, then feuded with Tice so bitterly that lawsuits flew and, as Kepner put it, “it’s easy to say Carrier basically hated everybody and was way off the deep end with the hate.”

Carrier’s split with Tice came after Bristol briefly flew the AHRA banner as the Spring Nationals. For a couple of years, AHRA gained a major foothold in the Southeast on Carrier’s turf, but the relationship collapsed in courtrooms and contract disputes as fast as it had formed.

Once IHRA was born, the battle lines sharpened. NHRA was the established national power, AHRA was the aggressive innovator and IHRA was the upstart tailor-made for places like Bristol and other tracks that craved attention and flexibility.

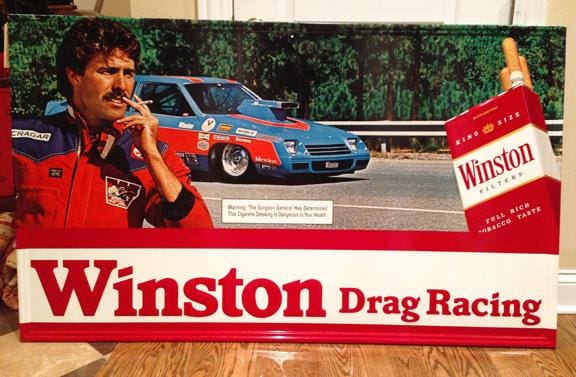

Then Winston changed everything. R.J. Reynolds executive Ralph Seagraves brought cigarette money into straight-line racing, and for a brief window the sport’s major sanctioning bodies appeared united under a single corporate banner.

IHRA actually got there first. The Southeastern series signed the initial points-fund deal with R.J. Reynolds, giving Carrier’s group the first real taste of big corporate sponsorship in drag racing. But, really, both were catching up to AHRA which had established a points fund years earlier.

But Carrier, always chasing a bigger stage, encouraged Seagraves to call Parks. Once NASCAR pushed NHRA to answer the phone and accept Winston, the dynamic changed overnight.

What began as “Winston Drag Racing” quickly turned into another battlefield. Carrier and Parks jockeyed to protect their share of the sponsorship, each understanding that Winston’s cash and marketing power could reshape their future.

Fans in the grandstands might not have seen the tug-of-war, but they felt the results in growing points funds and polished presentations. For the first time, national-event drag racing had the look and purse structure of big-league motorsports.

By the mid-1980s, however, NHRA’s size and national footprint tilted the board in its favor. More markets, more television potential and a bigger racer base made it easier for Winston to justify consolidating its drag racing investment with Parks.

When Seagraves retired in 1985, R.J. Reynolds walked away from IHRA entirely. Winston stayed with NHRA alone, and the points fund that started around $100,000 in 1975 ballooned to $2.3 million by the time tobacco pulled out after the 2001 season.

IHRA never fully recovered from losing Winston’s backing. The upstart that had once shared corporate billing with NHRA was now left hunting for replacement sponsors while Glendora rode out a quarter-century of Winston-fueled growth.

Even as the money shifted, AHRA’s fingerprints were all over the modern sport. Tice had perfected points funds, qualifying sessions and structured national schedules long before NHRA embraced the full model.

Where Tice and Carrier often acted like innovators, Parks acted like the editor. He watched what worked at AHRA and IHRA, then folded the best concepts into NHRA’s non-profit structure, trimmed the rough edges and occasionally acted as if the idea had always been NHRA’s.

The television war brought a fresh round of drama. While NHRA languished for years in syndicated tape-delayed packages that fans had to hunt down in local listings, IHRA landed on ESPN in 1983.

“ESPN didn’t know any better,” Kepner said. “They’re like, ‘Sure, we need drag racing, I guess, if we’re going to have all the sports.’” Every time NHRA called and said, “You don’t need that IHRA stuff, need NHRA, which is the biggest and best,” ESPN shot them down.

“The ESPN guys, the old school original ESPN guys, said, ‘We already got drag racing. We don’t need your stuff,’” Kepner recalled. For 16 years, IHRA owned that cable foothold while NHRA fumed on the sidelines.

That advantage eventually evaporated when Bill Bader, then controlling IHRA, burned the bridge to ESPN in a move Kepner called a mistake.

“The next hour, the NHRA jumped on ESPN and got the full boat deal,” he said.

Through all of that corporate maneuvering, NHRA maintained its strategy of starving rivals of public recognition. Kepner recalled how, even after landmark performances like Eddie Hill’s 4.99-second pass at an IHRA race, NHRA announcers refused to acknowledge where it happened.

At the next NHRA race, he said, “Trust me, the announcers didn’t say, ‘Here’s Big Daddy Don Garlits, who just won that gigantic $25,000-to-win race in Tulsa.’” To National Dragster and the on-mic talent, it was just “the Match Race Circuit,” a pointed way of erasing IHRA’s status as a bona fide national contender.

🔥 48-HOUR SALE! 🔥 Odd-lots, short-lots, closeouts & display shirts — all priced to move! 🏁 Get authentic https://t.co/jcAfIG1TiW gear for as low as $10 👕💥

— Competition Plus (@competitionplus) November 6, 2025

When they’re gone, they’re gone!

👉 https://t.co/ZWQRwUgEQb #DragRacing #NHRA #CompetitionPlus #PEAKSquad #Sale… pic.twitter.com/UOWDUKCRSP

The television war brought a fresh round of drama. While NHRA languished for years in syndicated tape-delayed packages that fans had to hunt down in local listings, IHRA landed on ESPN in 1983.

“ESPN didn’t know any better,” Kepner said. “They’re like, ‘Sure, we need drag racing, I guess, if we’re going to have all the sports.’” Every time NHRA called and said, “You don’t need that IHRA stuff, need NHRA, which is the biggest and best,” ESPN shot them down.

“The ESPN guys, the old school original ESPN guys, said, ‘We already got drag racing. We don’t need your stuff,’” Kepner recalled. For 16 years, IHRA owned that cable foothold while NHRA fumed on the sidelines.

That advantage eventually evaporated when Bill Bader, then controlling IHRA, burned the bridge to ESPN in a move Kepner called a mistake.

“The next hour, the NHRA jumped on ESPN and got the full boat deal,” he said.

Through all of that corporate maneuvering, NHRA maintained its strategy of starving rivals of public recognition. Kepner recalled how, even after landmark performances like Eddie Hill’s 4.99-second pass at an IHRA race, NHRA announcers refused to acknowledge where it happened.

At the next NHRA race, he said, “Trust me, the announcers didn’t say, ‘Here’s Big Daddy Don Garlits, who just won that gigantic $25,000-to-win race in Tulsa.’” To National Dragster and the on-mic talent, it was just “the Match Race Circuit,” a pointed way of erasing IHRA’s status as a bona fide national contender.

🚨 IT’S OFFICIAL — MODIFIED PRODUCTION IS COMING BACK! 🚨

— Competition Plus (@competitionplus) November 5, 2025

After more than four decades, NHRA is reviving one of drag racing’s most iconic eliminators — Modified Production — bringing it back home to Competition Eliminator where many believe it always belonged. 🏁

Stick-shift… pic.twitter.com/b0HLkApmJu

Yet for all the animosity at the top, there were adults in the room trying to keep the sport from tearing itself apart. Those roles fell largely to Steve Gibbs at NHRA and Ted Jones at IHRA.

Jones recalled Gibbs calling him to work out quiet agreements on rules “for the sake of drag racing.” One example was nitrous oxide on nitro cars, a brief, dangerous experiment in the early 1980s.

“Gibbs says, ‘Can we have a gentleman’s agreement that next year in the Rulebook you won’t be able to run nitrous oxide on the Top Fuel or Funny Car in either IHRA or NHRA?’” Jones said. “I said, ‘Yes.’ … So we both came out that year and said no nitrous on the nitromethane cars in the interest of safety.”

In another moment, Jones said Gibbs told him, “Our bosses don’t need to know about this, but for the sake of drag racing, there are times we need to line up on the rules.” The two quietly kept categories compatible enough that racers could cross over without rebuilding their cars.

According to Jones, Parks also separated his personal feud with Carrier from his view of other IHRA officials. Jones said Parks would greet him at banquets, walk across the room to shake his hand and say, “I know who you are. I know what you’ve done for drag racing.”

“The thing between me and Carrier is between me and Carrier. It doesn’t involve you,” Parks told him, Jones recalled. It was a rare glimpse of respect in a war more often defined by grudges and sniping newsletters.

Carrier, for his part, never let the feud cool. Jones said fans would tear the cover off Drag Review just to get to “Carrier’s Corner,” the inside-cover column where the Bristol promoter lobbed insults at NHRA officials with schoolyard glee.

“He gave Division director Lex Dudas the nickname “Lex Doo-Doo” and called fellow official Darwin Doll “Darwin Dolly,” Jones remembered. Parks was “the silk suit from California,” a label Carrier never tired of using.

In the end, IHRA’s founding owner made one more huge move he believed might finally push NHRA off its pedestal. Carrier sold IHRA to Funny Car star and Texas Motorplex owner Billy Meyer, who had grand plans to merge the two major sanctioning bodies into a single super-series.

From NHRA’s perspective, the real existential threat came not from Carrier himself but from the possibility of a combined schedule with Meyers’ vision and IHRA’s TV foothold. For one turbulent season, it looked like the sport might actually be reshaped.

Instead, the experiment collapsed under relentless rainouts, operational miscues and financial stress. Meyer’s grand merger bid died after a single season, leaving IHRA weakened and NHRA still standing.

Bader later took a serious run at making IHRA a strong national complement to NHRA, but his eventual sale to Clear Channel never matured into the powerhouse some insiders predicted. The sport’s three-way war quietly shrank to a dominant NHRA and a scrappy but smaller IHRA.

Carrier believed he was selling IHRA with the hope it would someday overtake NHRA. Instead, Parks wound up with what many close to the rivalry view as the last laugh.

Bruton Smith’s group bought Carrier’s cherished Thunder Valley and rebuilt it as Bristol Dragway, demolishing the original facility that had been both Carrier’s pride and Parks’ irritant.

NHRA officials didn’t just order the old tower removed. As Jones and others have recalled, they blew it up, capturing the demolition in photographs that raced around the drag racing world.

For those who remembered Parks’ warning that the Bristol tower would be “a monument to your failure,” the image of it disintegrating under dynamite felt like the punctuation mark on decades of bad blood.

Then fate added one more twist of irony. When Bristol Dragway created its Legends of Thunder Valley honor, both Carrier and Parks were part of the inaugural class.

The fact that Parks’ name now hangs high above Carrier’s picturesque mountain valley would have been enough, in many minds, to irritate Carrier even in the afterlife. The fact Carrier’s name appears first only adds fuel to the imagined argument.

Some who lived through the rivalry joke that it’s a wonder the letters on the building haven’t started fighting each other already. That, they say, would be the perfect final chapter for drag racing’s sanctioning-body wars – the names still battling for position long after the men, and their sanctioning bodies, stopped.