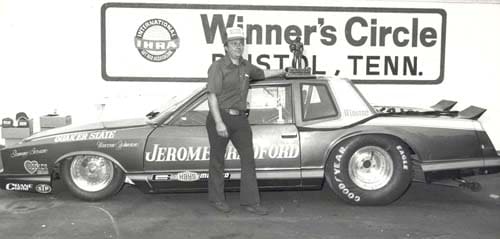

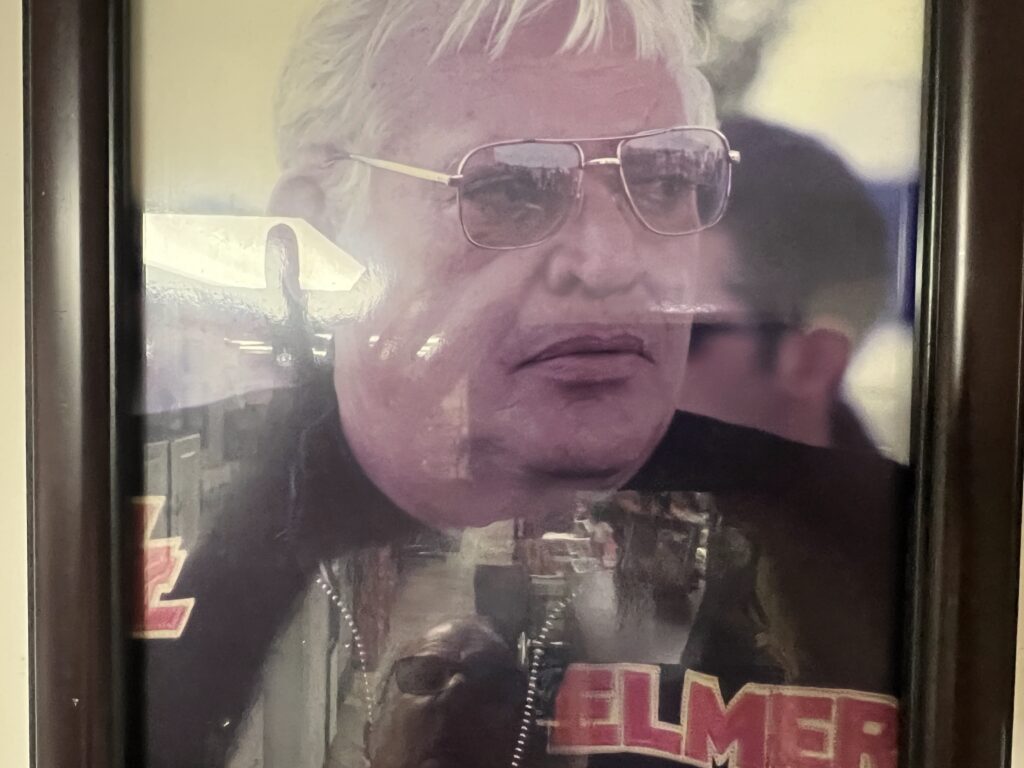

Thirty years after Elmer Trett died at the NHRA U.S. Nationals, Larry “Spiderman” McBride still talks about him in the present tense — not as a memory, but as a companion who never stopped going down the racetrack. Sept. 1, 2026 will mark three decades since Trett’s fatal crash at Indianapolis Raceway Park, and McBride says he has not made a pass since that day without wearing an Elmer Trett T-shirt under his leathers.

For McBride, the shirt is not nostalgia, and it is not branding. It is a private ritual built from a bond he calls inseparable, until it wasn’t.

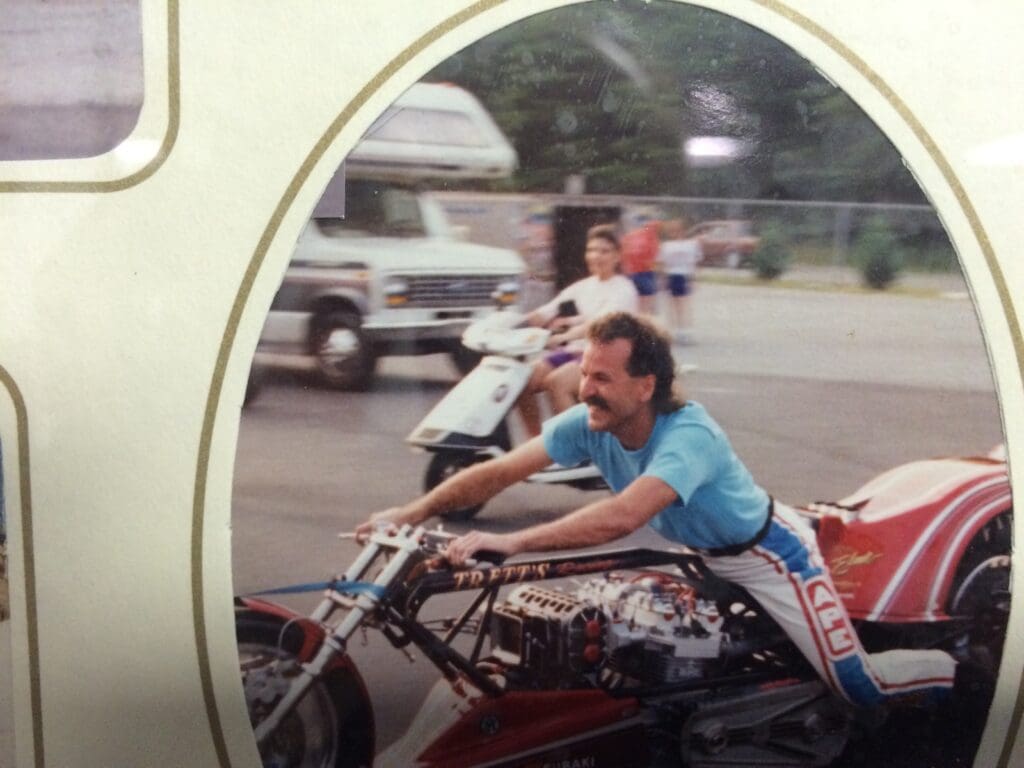

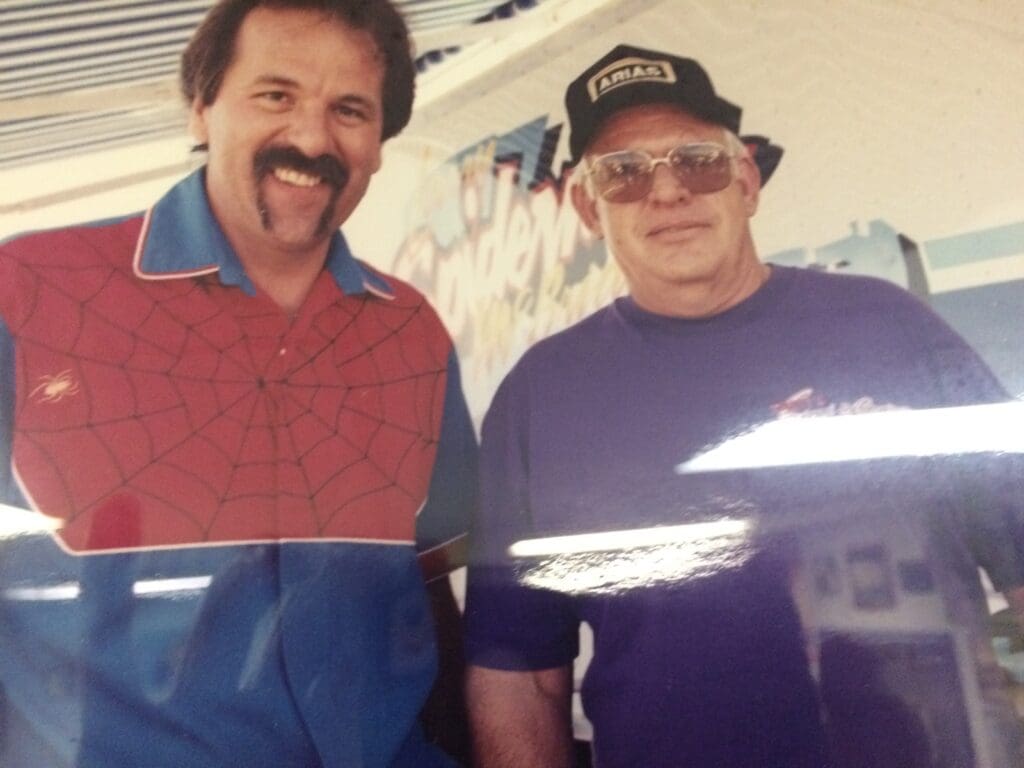

“it was a great relationship,” McBride said. “Elmer, I don’t know, I’m one of the few people that… Well, actually, I’m probably the only person ever rode the exact motorcycle that he rode.”

McBride said the relationship began the way most enduring racing friendships do — around trailers, tuning notes and respect that grows when someone keeps showing up. “Racing. I met Elmer in, God, I’m going to say, Bobby, 1978,” McBride said, tracing it to his time riding for Squeaky Bale and crossing paths through fabricator John Dixon.

He remembers Trett as a soft-spoken teacher whose words demanded attention because they were never wasted. “The thing about him, when he talked, you had to listen because he wasn’t a very loud talker, so you had to listen to what he said,” McBride said.

McBride said Trett didn’t just teach riders how to go faster — he taught them how to live inside the work. “We put our heart and soul in it,” McBride said, describing a routine that starts the moment a team gets home, unloading and tearing into the bike instead of letting it sit.

If Trett’s lessons formed McBride, one moment cemented the relationship into something closer to family. It came at Piedmont Dragway, in a match race for promoter Jim Turner, when Trett offered McBride something few riders ever touch: the exact motorcycle Trett raced.

“Just one day at Piedmont, he asked me if I wanted to ride his bike, and I thought he was just messing with me,” McBride said.

McBride said the offer didn’t come with ceremony, but it came with rules. “We had done a match race, I came back and he says… I opened a beer,” McBride recalled. “He came to me, he says, ‘I thought you was going to ride my bike.’ He said, ‘You can’t have no beer. Give me that beer.’ And then I made a pass on his motorcycle. Crazy.”

The pass mattered because Trett treated him like a peer in a world where Trett rarely needed one. “Well, I thought he was just joking. He wasn’t joking,” McBride said. “We go back and they get the bike ready and I made a lap on it and I went one-hundredth quicker than he did that day.”

“It’s so hard to even put it in words,” McBride said.

McBride said the ride was equal parts honor and terror because it was Trett’s equipment and Trett’s reputation on the line. “I was, man. It was unbelievable,” McBride said. “That deal, I was honored at the same time that he would ask me that, but it was humbling at the same time.”

Trett didn’t just hand over the bike; McBride said Trett stayed inside the moment with him, as if making sure the lesson landed. “And I did a burnout, and he pushed me back. It was crazy,” McBride said. “I made the lap, he came down the top end, picked me up, towed me back.”

McBride didn’t soften what it felt like to sit in the seat of the man he considered the standard. “So yeah, I was a nervous wreck,” he said. “And I still say to this day, if Elmer hadn’t got killed in ’96, I’d have probably been riding for him.”

Asked whether the ride was Trett’s way of blessing the next generation, McBride leaned into the idea. “I think so. I really do,” he said.

He described Trett as the kind of friend who invested in people when it would have been easier to protect his own advantage. “Elmer used to finance… In other words, you need a blower. Whatever I needed, he financed it,” McBride said. “And then I just paid him as we match raced.”

“Don’t ever tell anybody a lie about what’s in your motorcycle as far as the fuel system or timing or clutch,” McBride said Trett once told him. “Always tell them the truth, because they ain’t going to believe you anyway.”

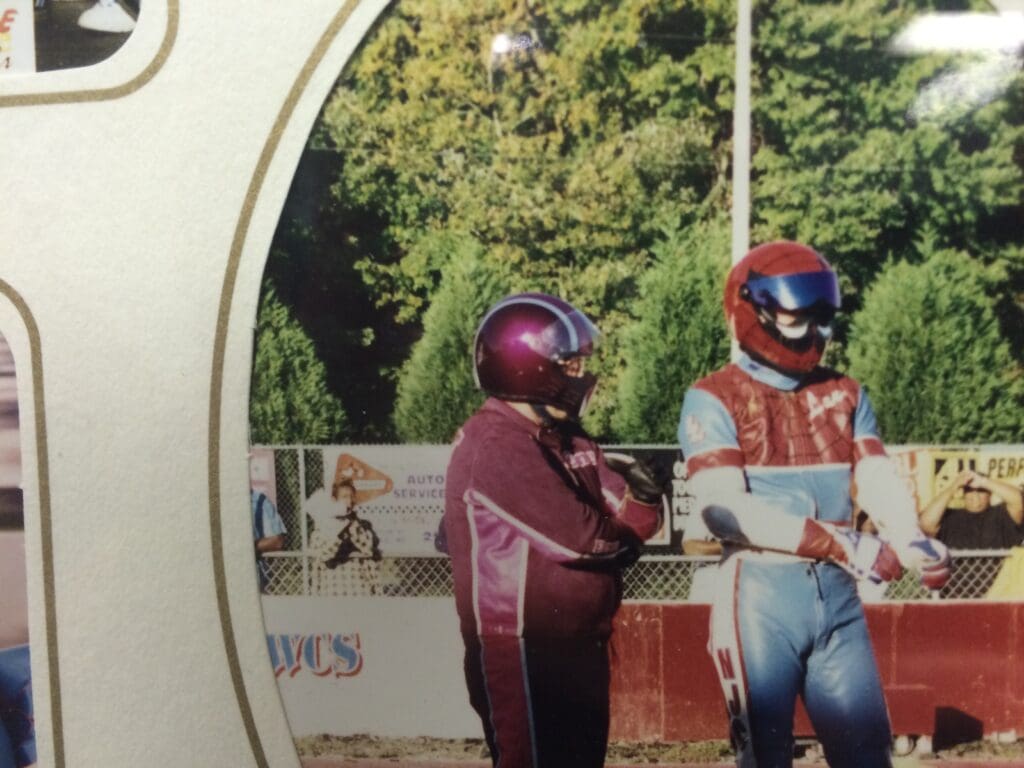

The story turns darker at Indianapolis in 1996, when Trett died during the U.S. Nationals weekend — a tragedy that came about a day after Top Fuel points leader Blaine Johnson’s fatal crash.

McBride said he was not watching from a distance when it happened. “In ’96, when he got killed, I was right behind him when he crashed,” McBride said. “In other words, I was the next pair down the track at Indy.”

“I remember I was going to quit. I said, ‘I’m done,’” McBride said. “When the man gets killed, it just kind of takes the wind out of your sail.”

McBride said Trett’s wife, Jackie, met him in the aftermath with a charge that changed his path. “And his wife told me the next day when they came back to the track, strong, strong people, she told me, she says, ‘Larry, it’s up to you now to keep Top Fuel alive. If you quit, it’s over with. You got to take what Elmer’s taught you and you got to keep going. You got to carry it on.’”

“And I said, ‘Yes, ma’am. I will,’” McBride said.

McBride said the pits knew quickly that it was not survivable, even before anything official was said, because the people closest to the incident carried the evidence. “Because we didn’t run. We all went back to the pits. We knew he wasn’t alive and what had happened,” McBride said.

He said the grief did not make Trett smaller in memory; it made him larger, almost untouchable. “That was a family member to me,” McBride said. “He was the, I’d say, the God of Top Fuel motorcycles. He was the Grand Poobah of the deal.”

“I don’t think anybody will ever surpass him. I’ve never tried to do that,” McBride said. “I’ve never been the one that wanted to be any better than Elmer. I wanted to carry his legacy on and be as good as him, but not never better because I don’t think you could ever be better than him, not only as a person, but as a rider and a person that had the same passion.”

McBride said the next time he went back to the racetrack, the absence was physical, like the place had changed shape. “It was almost an eerie feeling, being at the racetrack without him, because I’d always been at the racetrack with him,” he said.

“And the very first run, it was just a real eerie feeling,” McBride said. “And then you had to really do some soul-searching, ‘Do I really want to do this?’ The greatest in the world just got killed.”

If loss is what ended the inseparable bond, loyalty is what kept it alive.

“I’ve never made a pass since 1996 without an Elmer Trett shirt on, ever,” McBride said. “Anytime you see me, I’ve always got a white T-shirt on with Elmer on it. Absolutely. Never made a pass without it. Never will. He goes down the track with me every pass.”

The shirts are not pristine, and McBride doesn’t want them to be. “Oh God, man. I had a lot of them and I’ve been through a lot of them. Then we end up having to get some reproduced,” he said, explaining that some are worn out but still non-negotiable.

He called it loyalty, superstition and something spiritual all at once. “I’m very loyal in that way and superstitious, but that’s just my way so he knows that I’m still supporting him,” McBride said.

Then he added the line that explains why a piece of cotton can feel like armor in a sport built on risk. “The Holy Spirit’s pretty strong, bro,” McBride said.

McBride said he has looked for a successor — someone he could “knight” the way Trett informally did for him — and has largely come up empty. “I have and I’ve looked and I’ve tried,” he said, then explained that doing this at the level Trett set requires a specific kind of person with a specific kind of appetite for work.

He wants it for his grandson, too, but not at the cost of choice. “I’ve always wanted my grandson to do it, but I’ve never forced him to do it,” McBride said. “He may one day, but as of right now, no.”

“And then I don’t know if I could… I don’t know if my nerves would take it if he did it,” he added.

Asked about Pro Stock Motorcycle riders stepping into nitro, McBride cut straight to the reality of physics and posture. “Most of them guys are too small,” he said, then added, “you got to be a Nitro guy.”

He did name one who once expressed curiosity. “The only one that ever expressed any kind of interest in doing anything on one of them was Andrew Hines,” McBride said.

The weight of Trett’s influence can be measured by who showed up when the racing stopped. “Elmer’s funeral, anybody in the motorcycle industry, racing industry was there,” McBride said, describing a gathering that felt like a roll call of an entire community.

“Of course, I was honored to be a pallbearer. It was hard, but it was an honor, and I took it as an honor to do that,” McBride said.

McBride said he didn’t ride again that weekend and needed weeks to find himself in the aftermath. “I guess it was about three to four weeks to get my stuff together,” he said.

He credits faith for getting him through a period he describes as consuming. “I’m just glad that God was on my side to help me get through it, because it took everything,” McBride said. “It was a lot.”

And then, as often happens, grief circles back to something small — not the crash, not the headlines, but the voice on the phone. “I miss the phone calls till this day,” McBride said.

“This time of the night [early evening], it wasn’t enough for him to call me and be on the phone for an hour and a half at a time, and love to tell jokes,” McBride said. “We’d be talking serious, and then next thing you know, he would just break the monotony up a little bit with just a quick joke.”

Even the way Trett spoke — quiet, controlled — fits the legacy McBride describes: power without performance, strength without showing off. “He was a soft-spoken guy. But at the same time, people had a lot of respect for him because there was another side of him,” McBride said.

“He was a good man. He was a good hard man, but a good man,” McBride said.

And on Sept. 1, 2026, when drag racing marks 30 years since Trett died at Indianapolis, McBride’s tribute won’t be a ceremony or a speech. It will be the same thing it has been since 1996 — a worn white shirt under leathers, and one more pass made with his mentor riding along.