Originally published January 2018

The idea had merit, but in the long run, lacked longevity and support.

Former IHRA President Billy Meyer had the vision to simplify sportsman drag racing, and in one fell sweep kicked the popular Modified, Super Stock and Stock eliminators to the curb They were replaced by indexed bracket divisions ranging from 7.90 to 12.90 indexes.

Meyer wanted to simplify the explanation of grassroots racing to the casual race fan.

The plan was Factory Modified.

Factory Modified was created to retain the traditionalism of drag racing minus the handicap format with a platform which could be used to attract the attention of the American automobile manufacturers.

If Pro Stock was the equivalent of the NASCAR Winston Cup Pro Stock cars, the Factory Modified would play the role of the Busch Grand National cars.

The plan was to use Factory Modified as a feeder class for the Pro Stock division, a similar pathway as the alcohol cars provided for the nitro ranks. It was to be the highest ranking true doorslammer sportsman division since Top Sportsman at the time allowed for both full-bodied and open-wheel entries.

The Factory Modified concept became a popular subject of conversation for the Competition Eliminator contingent, primarily of the D/Altered and Econo/Altered classifications.

David Nickens, then a leading Competition Eliminator racer, jumped in feet first to the fledgling style of sportsman competition.

“Oh man I loved it and thought it was great,” recalled Nickens, who was part of the gigantic Castrol GTX sponsorship splash of the late-1980s.

Nickens found out quickly the politics of being a flagship NHRA racer and crossing the border of IHRA.

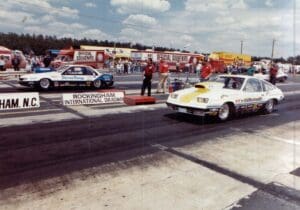

“I got in a lot of trouble with NHRA (when the IHRA) came out with that class,” Nickens explained. “I conceded that I was going to run all the NHRA National events and all the Factory Modified races, so it kept me from running the NHRA divisional events. So I did it that one year, I ran every NHRA and Factory Modified race and I won Rockingham and some of those races over there that year.”

The Factory Modified powerplants were potent, even if they did displace under 350 inches.

“The next year came along, and I sent my entry in to pre-enter for the NHRA events, and I never got any of my entry confirmations back. I called Steve Gibbs, and he said, ‘I don’t know what I can do for you because you didn’t run any divisional events last year.”

In those days, if you were a sportsman racer, and you wanted to run nationals events, you had better run divisional events.

The idea had merit, but in the long run, lacked longevity and support.

Former IHRA President Billy Meyer had the vision to simplify sportsman drag racing, and in one fell sweep kicked the popular Modified, Super Stock and Stock eliminators to the curb They were replaced by indexed bracket divisions ranging from 7.90 to 12.90 indexes.

Meyer wanted to simplify the explanation of grassroots racing to the casual race fan.

The plan was Factory Modified.

Factory Modified was created to retain the traditionalism of drag racing minus the handicap format with a platform which could be used to attract the attention of the American automobile manufacturers.

If Pro Stock was the equivalent of the NASCAR Winston Cup Pro Stock cars, the Factory Modified would play the role of the Busch Grand National cars.

The plan was to use Factory Modified as a feeder class for the Pro Stock division, a similar pathway as the alcohol cars provided for the nitro ranks. It was to be the highest ranking true doorslammer sportsman division since Top Sportsman at the time allowed for both full-bodied and open-wheel entries.

The Factory Modified concept became a popular subject of conversation for the Competition Eliminator contingent, primarily of the D/Altered and Econo/Altered classifications.

David Nickens, then a leading Competition Eliminator racer, jumped in feet first to the fledgling style of sportsman competition.

“Oh man I loved it and thought it was great,” recalled Nickens, who was part of the gigantic Castrol GTX sponsorship splash of the late-1980s.

Nickens found out quickly the politics of being a flagship NHRA racer and crossing the border of IHRA.

“I got in a lot of trouble with NHRA (when the IHRA) came out with that class,” Nickens explained. “I conceded that I was going to run all the NHRA National events and all the Factory Modified races, so it kept me from running the NHRA divisional events. So I did it that one year, I ran every NHRA and Factory Modified race and I won Rockingham and some of those races over there that year.”

The Factory Modified powerplants were potent, even if they did displace under 350 inches.

“The next year came along, and I sent my entry in to pre-enter for the NHRA events, and I never got any of my entry confirmations back. I called Steve Gibbs, and he said, ‘I don’t know what I can do for you because you didn’t run any divisional events last year.”

In those days, if you were a sportsman racer, and you wanted to run nationals events, you had better run divisional events.

SIDEBAR – WORKING THE SYSTEM – LEGALLY

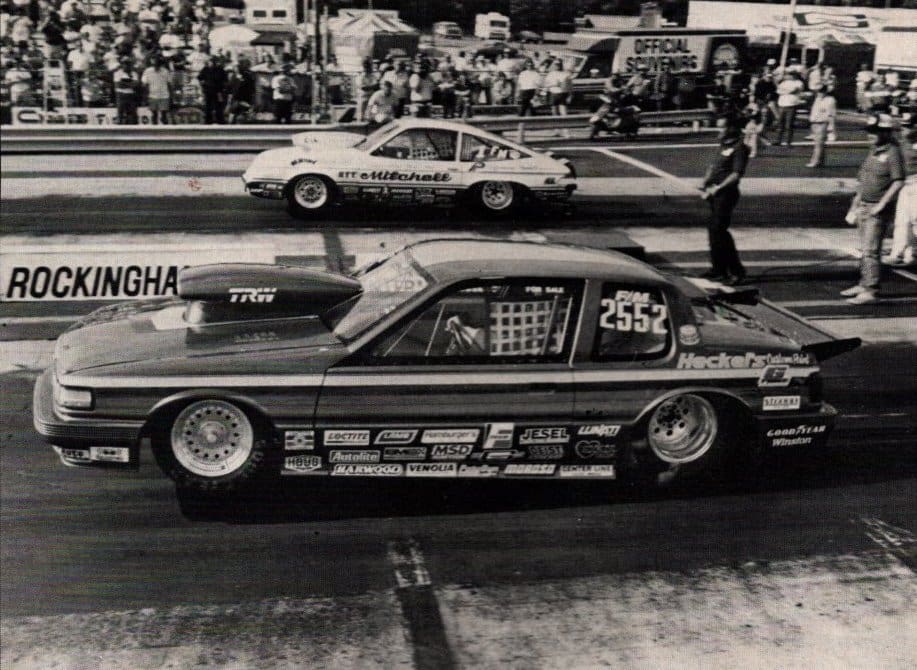

One of the beneficiaries of the inaugural Factory Modified format was five-time IHRA Modified world champion Dennis Mitchell.

Mitchell’s 1980 Monza was not exactly the kind of car Billy Meyer had in mind for the class, but it represented an entry, and this was clearly what the fledgling division needed.

The Huntsville, Ala.-based Mitchell had ruled the C/Altered division with an iron-fist during his championship runs starting in 1979.

He opted for Factory Modified over the redefined indexed-bracket system or racing NHRA.

Because the Factory Modified cars were included on the IHRA’s smaller point races, Mitchell took advantage of his competition who primarily used the IHRA point race weekends to go NHRA racing. He took advantage of the weak fields to gain points.

NHRA Comp eliminator standout Rick Hord dominated the 1988 NHRA schedule winning five national events and finished a distant second in the point championship.

Mitchell offered no apologies for winning the title by taking advantage of the rules placed before him.

“They scheduled the races, and we showed up to race,” Mitchell said in an interview after winning the crown. “We gave it everything we had, and in the end, it was good enough to win the title. That season was just a matter of just doing what we had to do to compete, that’s all.”

Just being a good class with close competition isn’t always a guarantee of longevity.

Randy Daniels, son of 1979 NHRA Modified champion Garley Daniels and a talented racer himself, raced in Factory Modified and later went on to a successful career in NHRA’s Pro Stock Truck.

“It was a real good class,” explained Daniels. “The six-cylinders never really had an advantage. We only qualified on the pole once, and we really worked our tails off to get within one or two-hundredths of them.”

Daniels confided the diversity in the class eventually served as a negative.

“It was just a deal where we should have gone with more than one carburetor and limited it to V-8 cars only,” confided Daniels. “There were one too many variables in the class. It was just not realistic to mix the automatics with straight-shift and the V-8s with the V-6s.

“I really hate to say it, but things turned political in that class, and there was a lot of bickering. There was fussing that the automatics got too much of an advantage and so on. The automatics were then whining that they needed more weight.”

Tim Freeman, another former Factory Modified standout who later migrated into Pro Stock car, won the first-ever race.

“I loved the class,” said Freeman, winner of the 1988 IHRA Winternationals crown in Darlington, SC. “The class really took off and I thought it was going to be really good. I think they could have gone with two four-barrel carburetors instead of the single four. That might have brought in more top names to run it.”

Just like Super Modified, Freeman agreed that lack of participation was the final nail in the coffin.

“There just wasn’t as much participation as there should have been,” Freeman explained. “I can’t help but to think if we had more cars that it might have worked out a lot better.”

For Nickens, the reality became apparent, after the first season. He simply couldn’t be in two places at one time.

“We were struggling to make it work because we had a commitment to it obviously and to run all of our NHRA races with our primary sponsorship,” said Nickens. “In my contract, it said that I had to pursue the championship. Well you understand that if you don’t run NHRA divisional races then you’re not pursuing the championship in the NHRA. We juggled it quite a big trying to make their races and trying to make all the NHRA races, doing what we can do. I think that year if I’m not mistaken we ran 30 or 35 races that year.”

But in the end, the failure of the NHRA to embrace the concept and politics proved to be the nail in the coffin.