Originally published August 2007

RELATED LINK – PART 1 – THE EARLY YEARS

Photos courtesy of David McGee, Norman Blake, IHRA Media, Dave Bishop

If one moment defined the Mountain Motor Pro Stock movement, it was the first-ever seven-second run. That day in April 1980, had the same effect on the class as putting a man on the moon had for space travel. It might as well have been. Seven-second Pro Stockers were science fiction in those days.

If one can consider it wrong to cross a time barrier, then Rickie Smith was the guilty party and the sports reaction caught him off guard. In fact, the hard-nosed racer feared he had done something wrong when an IHRA official sought to escort him back to the starting line. His transgression, a seven-second ET slip in winning the first round during the IHRA Pro-Am Nationals in Rockingham, NC.

“I was happy that I had won, but the next thing I know, I had a race official coming over to me and telling me to follow him,” Smith said. “I didn’t know what was going on. I thought I was in trouble. I had every thought running through my head that you could have. But, then I got to thinking, if you’ve done something wrong, they don’t usually pull you up in front of the crowd to throw the book at you.”

The only book the IHRA had in mind to throw at Smith was the history book. He had, in legal trim, traveled where no Pro Stock racer had gone – into the sevens.

Smith’s tow ended at the feet of IHRA President Larry Carrier who stopped the race long enough to personally present his 7.99 time slip. Bear in mind, the NHRA record was in the 8.30s at that time.

As is in every major performance barrier, there is usually one that can lay claim to the personal mark in testing or match race venues. Prior to Smith’s performance, the seven-second mark had already been breached by “Dyno” Don Nicholson during a 1978 Englishtown match race.

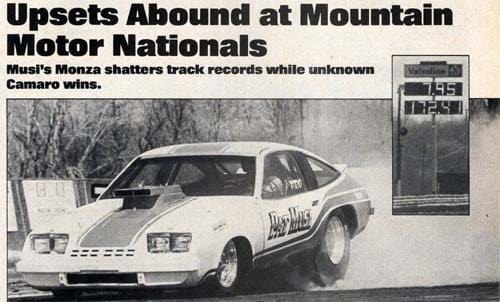

Pat Musi also did it at the same track. His Monza ran a 7.95 during a mountain motor open event with the legendary Super Stock and Drag Illustrated magazine on hand to legitimize it.

“Everyone is making claim to having that first seven-second run but I honestly believe we did it first,” Musi said. “Don Nicholson had tried to say that he went a 7.99 on a Wednesday evening in a match race. But, no one has ever come up with any real data to prove it. The first official seven-second run was plastered everywhere and photos of the scoreboard appeared in print.”

Musi ran a 7.95, but that run was followed up with a tire-shaking episode that was so violent that it launched the doors off of his Monza.

“Yeah, she had some power that day,” Musi said.

It took five months after Smith’s infamous run before another seven-second run. Suddenly, it was as if the 7.9-second zone was a mere launching point to the 7.80s as Warren Johnson became the second with an incredible 7.91 elapsed time. He later followed up the “legal” feat with a pair of unofficial 7.82 runs – back-to-back nonetheless.

Don Nicholson “officially” became the first into the 7.80s in legal trim almost a year after Smith’s feat with a 7.88 elapsed time.

Holley Carburetors stepped up with a seven-second club that followed in line with the Cragar five-second club for Top Fuel and Funny Car racers. The sixteen-member club filled up by September of 1982, the last ten coming within the same year.

One of the largest dividends yielded by the seven-second runs was the subsequent media exposure and match race demands. On a regular basis, Super Stock and Drag Illustrated ran features on this volatile combination of factory hot rods. But, with the seven-second runs, came eighth-mile laps that hovered close to the four-second zone.

That made the mountain motor beasts a shoe-in for the smaller eighth-mile venues looking to book a show.

“It was more justifiable for the tracks to book us in,” Roy Hill, one of the original mountain motor racers said. “Nitro was on the way of making themselves out of reach and we hadn’t reached that point. We were affordable at the time and gave a good bargain. The fans wanted to see us.”

And just think, it all started when Smith thought he was in trouble.

HEY YA'LL WATCH THIS!

The mountain motor fraternity often times had more intestinal fortitude than common sense.

Some say those early mountain motor cars were nothing but seven-second deathtraps. There was little engineering difference in a Pro Stock car built for a small block and 2,350 pounds than their mountain motor counterparts carrying 588 cubic inches and 2,400 pounds.

Warren Johnson speaks on authority because he ran both formats back in the day. He’s blunt when he says the majority of those (including his) cars were Ralph Nader specials.

Johnson said they were unsafe at any speed.

“The cars just weren’t built for the high torque engines that were put in them,” Johnson said. “The cars were flexible and they had the tendency to shake a lot. Knowing that, my primary objective in those days was to stay away from it. If you remained shake free and went from one end of the track to the other, you had about a 95% chance of winning the race. I concentrated more on clean runs than putting one of the bigger diesel engines in it.”

Johnson was never one for the huge displacement engines choosing engines that remained close to 500-inches. He ran a Rodeck block in his Monte Carlo.

Johnson makes no bones about one of his cars being the poster child for recklessness in those days. His 1981 Monte Carlo, originally designed as a dual purpose Pro Stocker, defined the word danger. It cleared IHRA tech with no problem but reportedly flunked at the one NHRA event it entered.

“That was an original concept car if there ever was one,” Johnson said. “Everyone had Mustangs and Camaros. We wanted to have some fun. That’s why we came out with the Monte Carlo and when you come out with a car that was designed with a mitre box and a square, you can only expect so much. It was so unusual that it became one of the more recognizable and photographed cars of its time. It stuck out like a sore thumb.”

Johnson said driving the car was a real experience, literally.

“Everybody should have driven it at least once,” Johnson said. “That was absolutely a white-knuckle special because it had no downforce on it. We couldn’t add spoiler to it because that would add lift. That car would black-track its way from one end of the track to the other.

“That would have been the ideal driver training car but we would have lost half of the drivers in doing so. Nearly every one would have crashed. That was a real driver training car. In hindsight, that car trained me for the old Hurst Cutlass that we ran.”

Johnson wasn’t embellishing on his stories. When Roy Hill makes comments on your car, then you truly have a “white knuckle” ride.

“I remember that old car that he used to call the Hulk,” Hill said. “It used to leave the starting line and looked like it was going to twist in two. It would hike that left front wheel into the air and it would be two feet in the air and the rest of the car would be planted there.”

Hill shouldn’t be so quick to laugh. At least Warren’s engineering didn’t produce a car that carried air through the car and out the rear window or took the finish line at 180 mph backwards.

“We all drove cars that we wouldn’t even dare sit in these days, much less drive,” Hill said. “I’ve gotten a little older and wiser these days. It didn’t happen back in those days, but it could have. I remember one time hitting the throttle in the staging lane [in a closed session] to get a feel of how the car would leave the line and the steering wheel came off in my hands.”

Hill wouldn’t say he cheated but he definitely pushed the rulebook and while he was at it, gave logic a shove or two.

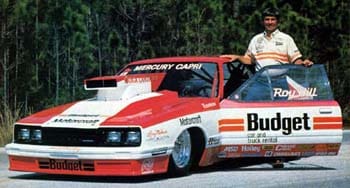

Case in point, Hill’s Mercury Topaz was the aforementioned engineering concept that channeled air from underneath the car through the transmission tunnel and out through an opening in a rear window. How did that car work out for him?

“It about killed me, that’s how well it worked,” Hill said. “That car was built in Florida by a guy that was in the limo business. It had a lot of neat ideas, none of which worked. The air would come underneath the tunnel and lift the rear wheels in the air.”

Hill had to pause to get the laughter out of his system.

“If you think that one was bad, then you need to go back to the Capri before that one,” Hill said. “It was built by Gary DeHart and I had engines from Dick Landy. Landy wanted me to get a Don Hardy car because he didn’t even know who DeHart was. Gary is now over the chassis engineering at Rick Hendrick’s. I had bought out his chassis business at the time and had him working with me.

“Well I followed Landy’s advice and got a Hardy car. One of the early runs, I got the car around backwards in the lights and scraped the quarter-panel down pretty good. I loaded it up and sent it back to Hardy.”

Hardy repaired the car and returned it to Hill prior to the NHRA Gatornationals. This was at a time when cars were easily interchangeable for NHRA and IHRA competition.

“I came through the finish line and the rear wheels were off of the ground,” Hill said. “They had a good view since their tech trailer was at the finish line. It was so bad they let me go back to my back up car after qualifying on Saturday.”

One would think the story couldn’t get more bizarre, but it did.

“I left Florida and drove straight to Detroit and put the car in the wind-tunnel,” Hill said. “What happened at 90 mph in that tunnel is that the wind would get between the cracks in the trunk and lift the car in the air. At 120 mph, there was no weight on the rear of the car at all.”

The oft-colorful Hill conducted his unique wind tunnel testing on the spot.

“I would cover that car in baby powder,” Hill said. “What happens is when you would get back you find where the air was going inside of the car. I had my own wind tunnel and that was a NASCAR trick that Harry Hyde showed me when I was with the Petty family. He used to tell them it was to make the car slicker, but what it did was show us where every single crack in our car was. We’d use a whole bottle of baby powder.

“When you see me out there with the baby powder today, you’ll know what I am doing. I’m reliving those old mountain motor days.”

Those were the days, Hill said, of the twisting three and four-link race cars. Hill added that he felt Reher & Morrison was the first team to get a handle on their car.

“That car left straight and I mean it didn’t twist,” Hill said. “We all used pan-hard bars and then we went to anti-roll bar and that stopped the cars from twisting. It made the cars leave level.”

Former racer and current engine builder Sonny Leonard said chassis legend Don Ness had a lot to do with advancing the safety aspect of the mountain motor cars.

“Don Ness was responsible for making these cars a lot safer in the early-to-mid 1980s,” Leonard said. “He was nothing short of being the master craftsman of that era. Ness made the big step when he came out with his three-link chassis. It advanced the chassis technology and (made the cars) better to handle. Ness was the crucial stepping stone.”

Johnson said in those early days the risk was simply par for the course.

“The tracks weren’t what they are today, nor were guardrails or the tires, so it had a lot of negatives working against it,” Johnson said. “But then again, the cars weren’t running as fast then as they are today.”

“General” Lee Edwards said the first mountain motor cars could be tamed somewhat through tires. The bigger the tire, the better the chance was for making a full run. At least that’s what worked for him.

“The cars were shaky and the tires weren’t so good,” Edwards recalled. “They really sat up high in the air. Then the tracks weren’t so good. But, it didn’t really affect me because I ran on such bad tracks match racing that I ran the great big tires anyway. I was the first to stuff 16-inch Funny Car tires in there and I’d run them at national events if the track was really bad.”

Edwards built his first Pro Stocker before entrusting Hardy and later Ken Hoger to build subsequent rides.

Leonard added that chassis and tires shouldn’t bear the complete blame for unsafe conditions. When he ran his Vega Pro Stocker in the late 1970s, the transmission could be a brute as well.

“The original Lenco transmissions run in these cars didn’t have a neutral in it,” Leonard said. “If you did a burnout, you had to keep that clutch to the floor. You did have a reverser on the thing. It was the craziest thing you had ever seen. You could put a neutral kit in there later. The first one I bought was used and I sold it and doubled my money. That was a good investment. If you bought a Lenco it was like money in the bank.”

THE FABULOUS MUSI MARATHON

Pat Musi and partner Joe Folgore were worlds apart on their thought process as they confronted a monumental challenge of chasing championships in both the IHRA and the NHRA tours.

That might not seem a radical proposition until you figure that Musi and Folgore planned to pull it off with the same car. They were looking at an unheard of then 23-race tour and that didn’t include the match races and those Mountain Motor Nationals stops in Englishtown and Budds Creek.

“There was little crossover back in those days,” Musi said. “The NHRA had their stars and the IHRA did too. We were the early IHRA stars – myself, Lee Edwards, Ronnie Sox and Roy Hill. It was an outlaw kind of thing and was a lot of fun.”

As if the schedule in 1981 wasn’t enough of an obstacle, Musi and Folgore added a couple of American Hot Rod Association stops for good measure.

Those who know Musi know he’s driven to win. In that year, Musi scored final round appearances in NHRA and AHRA competition and if not for a semi-final red-light might have made it in the IHRA as well.

Musi never considered himself in the clique of NHRA Pro Stock, but his mountain motor combination made him a welcomed IHRA and AHRA fraternity brother.

“They [the NHRA racers] looked down at us – being the guys who ran mountain motors and then came over to run the weight-per-cubic-inch Pro Stock,” Musi said. “I met Joe Folgore and the first thing he asked me is if I could beat Bob Glidden. I told him we needed budget and testing to make it happen. So we jumped over into the NHRA and they snubbed their noses at us.”

All except for one did the snubbing – the man himself, Glidden.

“He gave us respect,” Musi said. “We went out there and scored a runner-up in the first race. We got to the finals in Pomona and won the AHRA race. We beat Lee Shepherd in the second round in Pomona and people labeled that as a lucky win. In the semis in Gainesville, we left on him and beat him. I finished fourth in NHRA that year and seventh in the IHRA.

“I basically showed them that you have the same hard-worker attitude in the IHRA that you have in the NHRA.”

Just the opportunity to race against the drivers he deemed legends made it a worthwhile endeavor.

“I had always read about Ronnie Sox, Don Nicholson and Bill Jenkins and I got to race against them,” Musi said. “That’s one thing I was always grateful for this whole deal, I got to race them. They were tough and I was a young pup. I don’t think those days will ever return again. It was a neat time for me.”

Musi said his season reached its crescendo when the legendary Dyno man gave his father, the elder Musi, some suggestions about what his son was doing. Musi had nailed down a 7.95 elapsed time in an Englishtown mountain motor match race. This was before Smith’s IHRA 7.99 and after Nicholson’s 7.99.

“Nicholson came over to my dad after the seven-second run I made and told him, ‘you have to do something about your son, he’s just making us look bad,” Musi said.

That year, the marathon he completed made them all look bad.