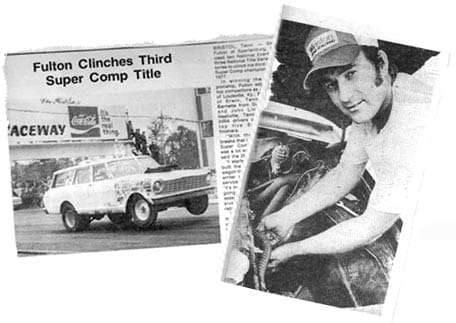

The story of the car that put Hall of Famer and World Champion Gene Fulton on the map

You can’t go through a 35-plus year career in drag racing without having a few odd moments.

For five-time IHRA champion Gene Fulton there was none odder and more defining than the day he first laid eyes on a 1964 Chevy II parked on a used car lot in Abilene, Texas.This car was no looker. In fact, it was the kind of car one might choose as a last resort, with the exception of Fulton.

Fulton saw something no one else envisioned. The end result was a race car which would go down in southeastern drag racing folklore as simply “that wagon Fulton used to have; that few could beat.”

That’s not a bad legend to have for a car that blew the engine on its maiden road trip.

Fulton is reminded of a less than pristine 1964 Chevy II wagon every time he walks in his engine shop in Spartanburg, SC., Fulton Competition. Sweet memories of his days of winning three world championships with a car he bought in 1970 for less than $200.

This car, he proudly proclaims, paid for the shop he uses to build five-second nitrous engines.

“That car was so good to me for so many years,” Fulton recalled. “It bought and paid for the place that I am in today. It owned the engine shop I have today, not me. I’ll always remember it that way. That is the car that put me on the map.”

At times the greatest experiences have the most humble of origins.

Fulton did time in Vietnam during the late 1960s and in his last year of service compiled an impressive collection of high performance parts. He was going to build a racecar; he just didn’t know what kind.

He found his prototype car on the car lot outside of Dyess Air Force base in Texas and it was nothing short of a sarcastic beast – 194 inches of Chevrolet engine and a column shifted manual transmission.

The wheelbase on this wagon is what Fulton believed made it a winner. The grocery getter looked like a car that had a long enough wheelbase to grab those marginal tracks in the Carolinas.

Fulton knew he needed to get the car home before he could entertain any of those visions.

An easy proposition you say? Not hardly.

Fulton began the 1,100-mile trek from west Texas to the upstate of South Carolina and encountered no significant problems until he reached Alabama.

A routine gas stop led to zero oil pressure.

“I had no idea what I was going to do at that time,” Fulton said. “I turned the car off and sat for a moment. Then I went through the normal routine of checking the oil and I cranked it up, the light came on, and I believed something had stuck in the oil by-pass.

“I cranked the car up and I matted the pedal and turned it off.”

True Fulton magic, the oil light went out.

“I knew at that point I had saved my ass,” Fulton stated proudly.

Fulton reached the other side of Atlanta when the little six-cylinder began to rattle. He reached Lake Hartwell, roughly 45 minutes from Spartanburg, and the situation got worse. He stopped at a pay phone and called his sister.

His sister, another sister and a brother-in-law came to his rescue.

“We hooked a rope to the wagon and towed it to Spartanburg on Interstate 85,” Fulton recalled. “My sister and I sat in the back and just talked away, catching up on lost time.”

Fulton got home and started tearing down the wagon, beginning the initial transformation from street car into racecar.

“I had a plan and this wasn’t going to be an accident,” Fulton admitted.

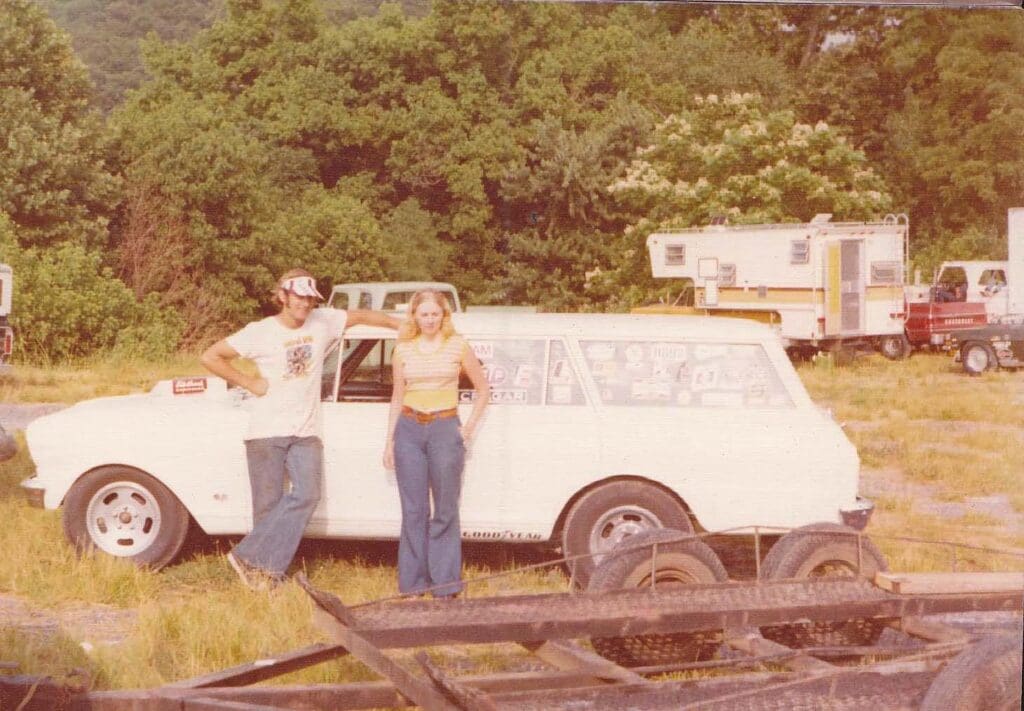

Fulton replaced the tired six-cylinder with a 302 cubic inch small block Chevrolet. The wagon would go on to host anywhere from a 262 cubic inch to upwards of 350 cubic inches in the span of eight years. These moves were contingent on the weight breaks afforded the classes.

“The wagon had really good traction,” Fulton revealed. “The tracks were so poorly prepared that running on them was like running on the street in front of my shop. Traction and mechanical dependability meant everything back in those days. The driver figured into the equation because there were none of these gadgets or reaction timers.”

Fulton introduced the wagon to the national event scene in 1972. He lived 150 miles down the mountain from Bristol, Tenn., and without a truck and trailer, he flat-towed the car up the winding two lane of NC Hwy 19/23 – not exactly the ideal towing scenario.

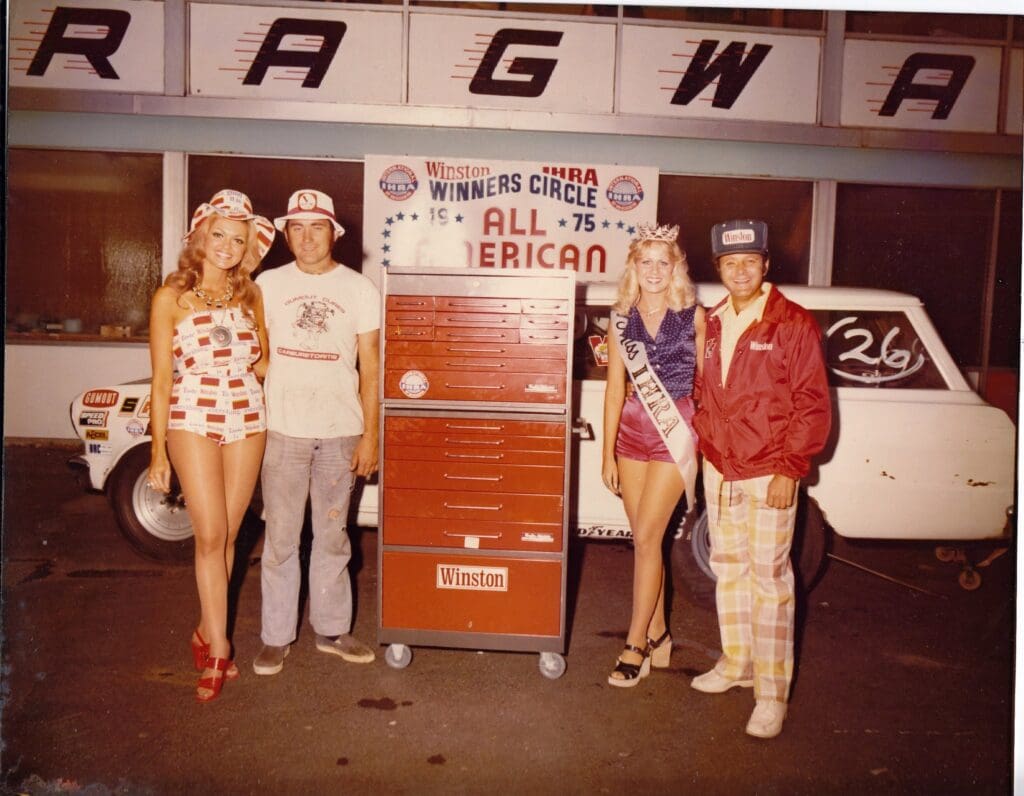

“It had rained and the car was completely dirty from road dirt,” Fulton said. “I remember some of the guys laughed at me and said my car was a joke. No one was laughing on Sunday when I took home all of their money.”

Through thousands of round wins and hundreds of thousands of dollars in prize money, no one ever laughed again at his little wagon.

This 3,500 pound beast, complete with a Doug Nash 5-speed transmission was no joke. Did we mention that it carried a Dana rear-end?

Fulton became a killer in the early days when handicap starts were doled out on body lengths. The combination of naturally great traction tendencies worked in his favor.

“There were times when I didn’t take the handicaps because the car had such good traction, I could beat the quicker cars,” Fulton said, voice cracking with laughter.

Fulton knew there would be a day when the competition would catch on to his game plan. By 1977 reality set in.

“Racing was changing so fast,” Fulton said. “I really hadn’t considered changing because Modified had become nothing more than a bracket race. That combination that had dominated so much in the early days didn’t matter as much by then.

“It got to the point where the class really became competitive.”

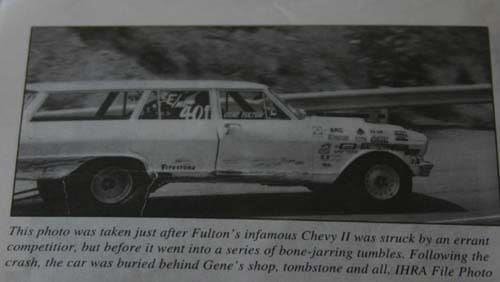

Fulton accepted the fact that the season might be his last for the wagon before seeking a new car. On a fateful day in May of 1978, another racer made the decision for him. Well, not really, Bell’s broken race car did.

Lanny Bell, a driver who would go on to win the 1978 Modified title, broke a spindle Sunday morning at the IHRA Spring Nationals in Bristol, Tenn., sending his Vega into Fulton’s lane and striking the wagon.

“I was just cruising along and everything was just fine,” Fulton remembered. “All of a sudden I got blind-sided so hard that it turned the car sideways and it rolled onto its side. All I remember was the horizon through the windshield.”

Fulton braced for the worst.

“When the car starts to flip you encounter this overwhelming shock. The adrenalin and every emotion hits you. Then you realize, ‘So this is what a crash is like.”

“I figured I was dead at this point and even though everything was going crazy outside, I felt peaceful inside. I wasn’t the least bit scared. Then it went bam, bam, bam, bam, bam, bam and then it stopped. I didn’t feel any pain or fear while the crash was going on.”

Once the mangled wreckage came to a stop and Fulton exited under his power, then effects hit him all at once.

“I felt it then,” Fulton added.

Fulton was no stranger to carnage having been in Vietnam.

He had flown aboard C130 cargo planes high above all of the action on the ground. In those days the C130s were used to drop supplies into fire bases and the troops on the ground.

The C130s were also used to transport wounded soldiers to the various hospitals throughout the theatre.

He also encountered enemy fire during many of his missions and that adrenaline rush prepared him for the challenges of drag racing.

Seeing the soldiers in various critical stages of medical condition also prepared him for the reality that he had drifted close to his own mortality in the crash.

“Anything could have happened in that crash and I’ll be the first to say that I was lucky to get out of there like I did,” Fulton said. “The first injury was a smashed finger and it was just like someone had smashed it with a ball peen hammer and to this day that finger is still crooked.

“My [left] arm was like someone had dragged it on the asphalt. And, it had. It was outside of the window at one time during the crash. It had glass embedded in it and to this day, if I have an x-ray, you can see the glass still in there. I’ve had little pieces over the years make their way out through sores.

“I didn’t have a proper brace on the seat [an illegal seat by today’s standards] and it had broken to the point where it just beat me against the roll cage. From my head to my buttocks was beaten black and blue.”

The most serious of Fulton’s injuries was a bruised lung caused by the bout with the roll cage, which caused him to spit up blood while waiting on medical treatment.

“I’ll never forget asking the little girl on the ambulance if they had an oxygen mask,” Fulton said. “I was spitting up blood really bad and needed the oxygen. She had to look through the whole ambulance and finally ask the driver if they had oxygen. They had no idea how bad it was.”

Remember the severe asphalt rash on his arm?

“She covered it in betadine and took this brush and started scrubbing it,” Fulton recalled. “That was some serious pain.”

Fulton spent a night in the Bristol hospital and could hardly walk the next day.

“I was sick because my car had been a major investment for me,” Fulton said. “I was whining about the car and it was two weeks later when [Super Stock legend] Bobby Warren called me to see how I was doing. He let me know it was time to be a bigger man and move on. That was a big influence on me because I built a new car and returned to racing a month later.”

Fulton retains a measure of resentment regarding the crash.

“It was pretty bad when you go to race and the guy in the other lane runs all over you and destroys your car because of his incompetent car,” Fulton added. “He didn’t even say he was sorry. If I had done that I’d feel awful. It was a lot different back then because we had everything in our car.”

Today all he has are the memories of the wagon and those work well for him.

Fulton said he and wife Kay recently pulled out the old financial books related to the winnings accrued while racing that car and the success of the car floored him.

For instance, for the two year period of 1973 and 1974, Fulton competed a minimum of three nights a weekend close to home. The purses weren’t that large, maybe $400 on a big weekend, but then again in today’s racing world those winnings would be multiplied by ten.

Fulton estimates back in those days he won as much as $50,000 a year.

He won as much as $13,000 in one month during the 1974 season.

But on one May afternoon, Fulton and his shop constituents dug a hole and buried the money-maker out back. That day signaled the end of an era.

Or did it?

“There’s a part of that car that went into every ride I had from that point on,” Fulton surmised. “That car lived on for many years after that accident.”

BOBBY BENNETT: NHRA DIDN’T ANOINT ITS NEXT FACE — MADDI GORDON TOOK IT