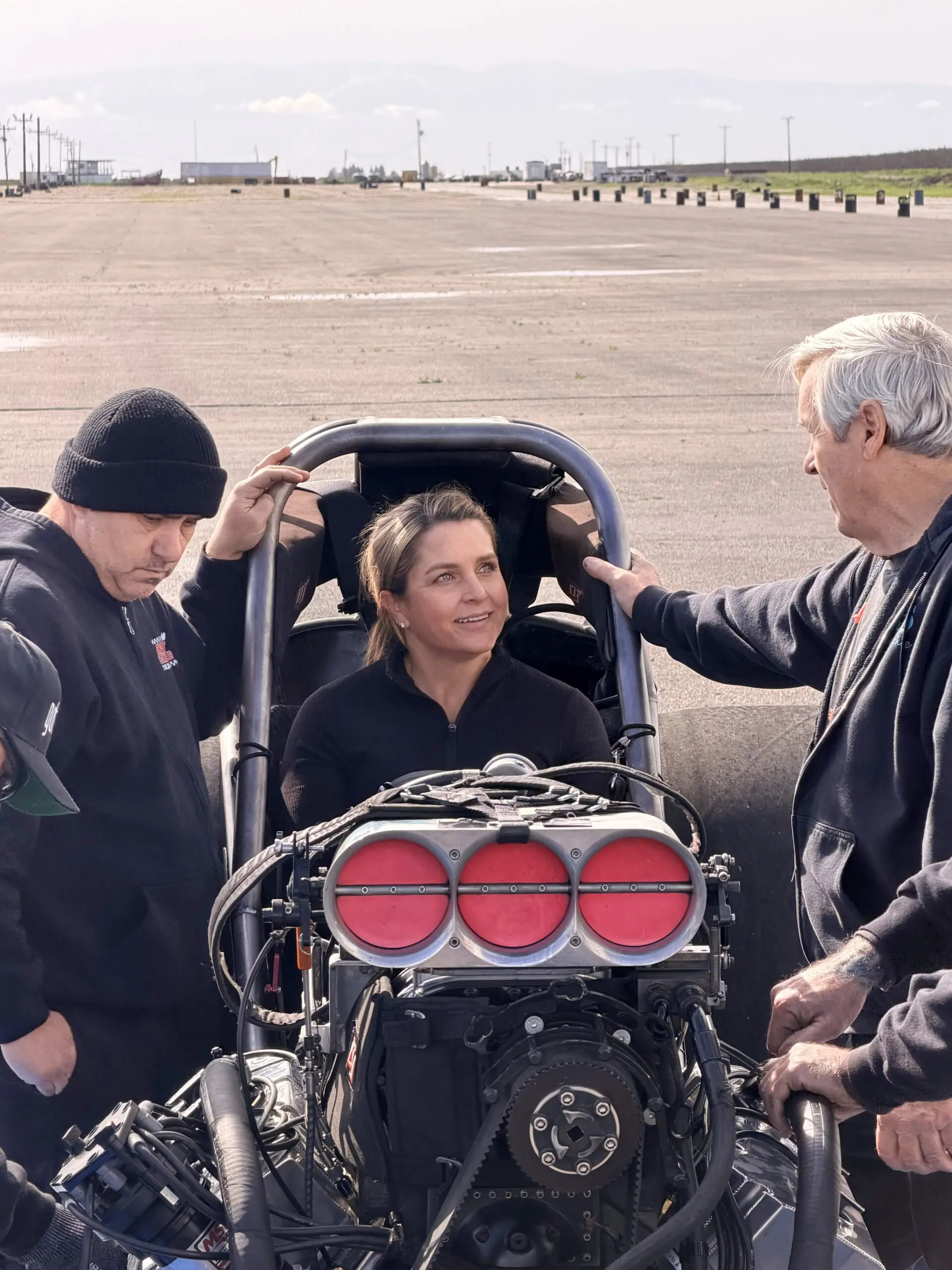

Billy Glidden doesn’t mince words. He didn’t call it a comeback, because in his words, “We needed somewhere to run the car.” That was the reality behind his recent appearance at a PDRA event in Martin, Michigan, the latest chapter in a career shaped by grit, frustration, and pure love for the sport.

Glidden, the son of 10-time NHRA Pro Stock champion Bob Glidden, has never cared much for appearances or headlines. His return to competition wasn’t about winning or chasing points—it was about making laps, collecting data, and seeing what a resurrected piece of doorslammer history could do under power.

“In fairness, I don’t consider that went there racing,” Glidden said. “We certainly wouldn’t go to one of those races with our small block in the car and expect to accomplish anything. There were 17 cars and we were the 16th quickest.”

The car in question—a Chevrolet Beretta originally built by Don Ness for Ron Krisher—never made it to Pro Stock. It had spent time in Comp Eliminator before falling into Glidden’s hands, in need of significant help.

“When I got the car, it didn’t even have an anti-roll bar in it,” Glidden said. “It went to two chassis shops and… they failed really, really badly. Shannon and I brought that car home and, in the back of the shop here on the floor, cut it all apart and rebuilt it.”

Glidden wasn’t exaggerating. He gutted the car to the bones. From A-arms and steering to engine placement and transmission alignment, the work was done with his wife Shannon in their shop—no big teams, no fancy haulers, just old-school drag racing determination.

He still has his small-tire Fox-body Mustang, but the rig hasn’t moved much since 2021, save for the occasional Mickey Thompson test. This time, they ventured out to Kil-Kare Raceway for a test session ahead of the IHRA race in Columbus. The trip was nearly derailed 40 miles from the track.

“We blew the passenger rear trailer tire,” Glidden recalled. “As I’m pulling my head out from under the trailer, the airbag exploded.”

It wouldn’t be the only tire failure of the weekend. Another blew on the return trip, followed by yet another 15 miles later. Fortunately, longtime friend Nick White was caravanning behind them and provided a stopgap solution—and a truck.

“Nick stayed with the rig while I drove home to get a tire out of the shed,” Glidden said. “We got back around 1 AM, changed the tire, and I set the cruise at 44. We came home going 44 or less.”

The tire problems didn’t stop there. Just 80 miles into the trip to Michigan, a tire delaminated. Glidden replaced it with an old spare he hoped would make the 600-mile round trip.

“It was the coolest running tire on the whole rig,” Glidden said. “We stopped multiple times checking tire temps, so it really wasn’t a temp issue.”

It wasn’t just the trailer giving him grief. The engine they started with barely made it through a handful of runs before breaking a rod. Glidden swapped in a backup that had never been in the car. Nothing fit.

“We ended up taking the whole oil system off the engine and remounting it—from the oil pump to the can,” Glidden said. “We missed Q2. Then we went out in Q3 with the different engine and went 4.13. That was really good.”

Even the clutch pedal fought back. The original, one of the few things he hadn’t rebuilt, bent badly under load. On every pass, it flexed enough to let the car roll through the beams. Glidden believes he finally corrected it after the event.

“That’s some of what happened the first round,” he said. “Most of it was driver error, but the clutch flexing like that—it just jumped.”

If all that wasn’t enough, he was also troubleshooting wiring. During the car’s first burnout, a disconnected wire kept the car from backing up. “They had to run out and push me back,” Glidden said. “Then I just ran it a bit through first gear.”

From aborted runs to early shutoffs and finally a competitive 4.13, Glidden was simply gathering information—and fighting mechanical gremlins every step of the way.

“This was car, driver, and crew training,” he said.

Glidden and his team—wife Shannon, Nick White, and sponsor Mark Young—don’t have major corporate backing. Young, whom Glidden calls their “fairy godfather,” kept the tow truck in tires and outside of being an instrumental part in Glidden’s return, puts on one race a month at Ohio Valley. Glidden plans to run the next one, pending good weather.

“Basically, steel body car and no billet,” Glidden said of the rules. “We did go there with a small block, and it’s already far exceeded what I felt it should be able to run the way we were set up.”

The PDRA event worked well for what Glidden and his team needed to accomplish.

“That track was just really, really good,” he said. “You could tell that by how quick and fast everybody was running there.”

So, did he have fun?

“My wife and Nick, our buddy, both claimed they had a great time,” Glidden said. “Me, it’s just stress-filled.”

That’s the Glidden way—no sugarcoating, no illusions. It’s not about chasing trophies or recreating his father’s legendary success. For Billy Glidden, drag racing remains a test of will, resourcefulness, and raw mechanical effort.

“We worked our butts off and didn’t seem to accomplish anything,” he said.

But for anyone paying attention, his presence in the lanes—with a resurrected car, a handful of tools, and a trailer full of patched tires—meant a whole lot more than he’s willing to admit.