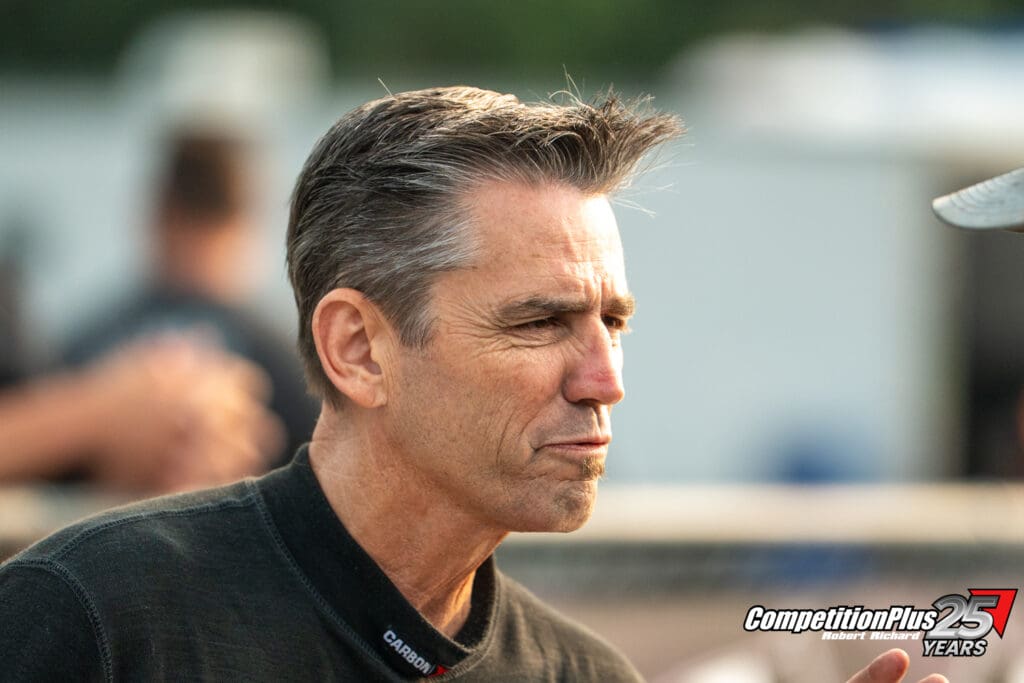

Sometimes it takes a lifetime in drag racing to understand what fulfillment actually looks like. For Larry Dixon, a three-time NHRA Top Fuel world champion with 62 national event victories, that understanding has arrived not through another trophy, but through perspective.

“If I never win another national event or even race a full season again, I’ve done more than I ever thought I would,” Dixon, NHRA’s third-winningest Top Fuel driver, said. The comment is not delivered with resignation or nostalgia, but with certainty.

Dixon does not speak like a man chasing one more championship. He speaks like someone who has already outrun the expectations he carried as a kid watching his father race Top Fuel and wondering if he could ever belong at that level.

The numbers attached to his career remain staggering, with championships in 2002, 2003, and 2010 and victories spread across multiple eras of the sport. Yet Dixon now measures success less by results and more by alignment with the life he wants to live.

The modern Top Fuel grind demands total commitment, four qualifying runs compressed into two days, and the expectation of four more rounds on race day. Dixon acknowledges that version of racing no longer defines what fulfillment looks like for him.

Instead, his priorities have shifted toward family, flexibility, and purpose. That shift does not signal a departure from Top Fuel, but a redefinition of his role within it.

Last season offered a reminder that Dixon still knows how to race when the opportunity makes sense. He entered an IHRA event late in the year and drove to the final round, reinforcing that competitiveness was never the missing ingredient.

That runner-up finish at Darana Motorsports Park in Columbus, Ohio, may stand as Dixon’s final appearance in a single-seat Top Fuel dragster. If it does, he is comfortable knowing it happened without pressure or unfinished business.

Asked how often fans might see him racing again, Dixon framed the answer with clarity. “With one seat or two?” he said.

The distinction matters. Dixon no longer views the single-seat car as the sole expression of his connection to Top Fuel.

“There’s no hard concrete plans with me in the Top Fuel car this year,” Dixon said. “A West Coast guy, Jaren Mott, is going to get licensed in my Top Fuel car at Gainesville next month, and then if all goes well, we’ll go to Phoenix.”

That is as far ahead as Dixon is willing to look. “That’s as far into 2026 as I’m looking right now,” he confirmed.

The limited scope is intentional. Dixon has reached a point where overcommitting feels unnecessary.

Dixon now finds himself increasingly fulfilled outside the driver’s seat. The business side of Top Fuel and the opportunity to introduce others to the category have become central to his involvement.

“To be honest with you, with my age and holding a license for 30-some years, I feel like I did my time and had a blast,” Dixon said. “But I love the sport.”

That love is precisely why the two-seat Top Fuel dragster exists. Dixon did not build it as a novelty or side project.

“I loved Top Fuel before I ever got my Top Fuel license,” Dixon said. “And me not being on tour, I still love Top Fuel.”

Dixon believes passion does not require constant participation. He sees value in contributing wherever it makes the most sense.

“Wherever I fit is probably where I’ll be,” Dixon said. “And more often than not, it’s not with me in the seat of the single-seater.”

Instead, Dixon views his role as paying the sport forward. He wants to stay visible, involved and useful without forcing himself into a full-time role he no longer needs.

Age is part of the equation, but Dixon does not frame it as limitation. “I never imagined myself driving a Top Fuel car at 60,” he said. “I’ll be 60 this year, so take it for what it’s worth.”

For Dixon, the realization is not about slowing down. It is about choosing how to spend his time.

“There are a lot of other things in life,” Dixon said. “My youngest, Luke, is starting to drive and race, and that excites me.”

Dixon said investing in his son’s development matters more to him now than adding races to his own resume. “I want to put more effort into him than me being behind the wheel,” he said.

He respects drivers like Chris Karamesines and John Force who competed deep into later decades, but longevity behind the wheel was never one of his aspirations. Dixon said watching Force compete for as long as he did left him impressed, but it was never something he wanted for himself.

“Those were never my aspirations, to drive into my 60s, 70s or 90s,” Dixon said. “It’s being involved, but not necessarily behind the wheel.”

That distinction has guided his decisions over the last several seasons. Dixon is not stepping away; he is repositioning.

Dixon does not believe his perspective is universal. “It’s not for everybody to do it for the rest of their lives,” he said. “I love it, but I love other things too.”

Those other things increasingly revolve around family experiences. Dixon recently traveled to California with his family to attend the Rose Parade and the Rose Bowl after his son began school at Indiana University.

“The football team were great hosts and they put on a heck of a show,” Dixon said. “Those are things that I’m enjoying, and I did it with my family.”

That mindset carries into how Dixon approaches his son’s future in racing. He does not want to dictate a path or recreate his own journey.

“My dad gave me the love of the sport,” Dixon said. “I had to figure out how I fit into it.”

Dixon believes his son deserves the same freedom. “My blueprint wouldn’t be the same to give to my son,” he said.

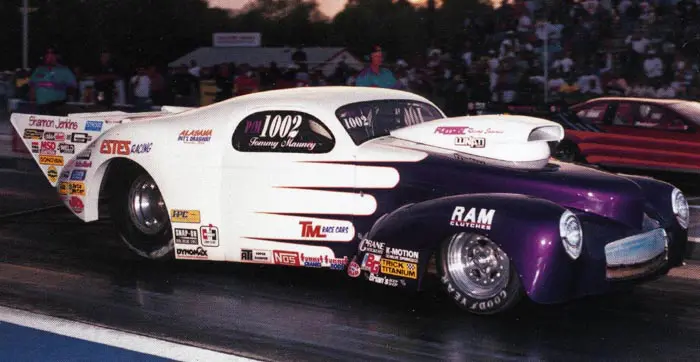

Luke raced Super Comp on the West Coast at regional events last season. Dixon never raced Super Comp in his career, a detail he finds telling rather than troubling.

“He’s forging his own path,” Dixon said. “And it’s exciting to see where it goes.”

Dixon’s appreciation for drag racing has only broadened with time. He now sees the sport as a collection of opportunities rather than a single destination.

“When I was younger, I would say Super Comp,” Dixon said when asked which Lucas Oil Series class might have appealed to him outside the top alcohol ranks.

He also pointed to Top Dragster as a category that would have caught his attention had it existed earlier. “There are so many cars that show up, and it looks like a ball,” Dixon said.

Super Street still resonates with Dixon as well. “A lot of those look like street cars,” he said. “That’s kind of my roots.”

To Dixon, drag racing’s greatest strength is its inclusivity. “There’s a category that could be a home for everybody,” he said.

That belief aligns directly with the mission behind his two-seat Top Fuel dragster.

“When I get done at the end of the run and see the smiles and tears on people’s faces, that’s a very satisfying feeling,” Dixon said. He believes the emotional impact rivals anything he experienced chasing championships.

Certain moments remain especially powerful. Dixon recalled a run at US 131 Motorsports Park that left a lasting impression.

“I can tell that story about Mr. Russell and I still get goosebumps and tears,” Dixon said, referencing Burnell Russell, who wanted to understand what excited his son about fuel racing.

Dixon felt the same emotion later giving John Bandimere Jr. a ride at the same facility. Those experiences reshaped how he defines success.

“I got plenty of trophies and I’m happy with the ones that I have,” Dixon said. “But being able to create memories for people like that with that car, that’s equally or more satisfying.”

Even the logistical challenges reinforce Dixon’s appreciation for the process. He described a weekend where both the single-seat and two-seat Top Fuel cars ran on the same day with limited resources.

“We ran the two-seater on the first run, swapped cars, and qualified for the show that afternoon,” Dixon said. “Both runs were perfect.”

Without multiple haulers or a large staff, the team executed cleanly. “It was like being a big show team without being a big show team,” he said.

Financial reality remained unchanged. Dixon acknowledged that running a Top Fuel car without sponsorship is expensive and rarely profitable unless a team wins.

“We were still behind, but I still had a great weekend,” Dixon said. The freedom to operate without obligation mattered more than the balance sheet.

The final-round appearance validated preparation, not ambition. Dixon did not leave the weekend searching for the next one.

Dixon’s relationship with Top Fuel has evolved, not faded. He no longer measures his connection by race count or championships.

If the Darana Motorsports Park runner-up finish stands as his final single-seat appearance, Dixon accepts it without hesitation. He views it as a chapter closed on his own terms.

The legacy he values most now lives beyond record books. It exists in shared experiences, family moments and the opportunity to introduce others to the raw force of Top Fuel.

“I’ve got plenty of trophies,” Dixon said. “But seeing what that car does for people, that’s something I’ll never get tired

of.”