Jack Wyatt has never measured his Funny Car career by championships or headlines, but by persistence. As he enters his 50th consecutive year racing Funny Cars, Wyatt stands as a rare constant in a sport defined by constant change.

The milestone reflects not a single achievement, but decades of survival across multiple eras of drag racing. Few drivers remain active across five decades, particularly in a category that demands continual adaptation just to remain competitive.

“I started in 1976, and I wouldn’t have thought that, but that’s pretty much consecutive years. We’ve run them every year, even though I worked for other bigger teams, I’d at least run my Funny Car a couple times that year, but yeah, really starting to show my age now,” Wyatt said.

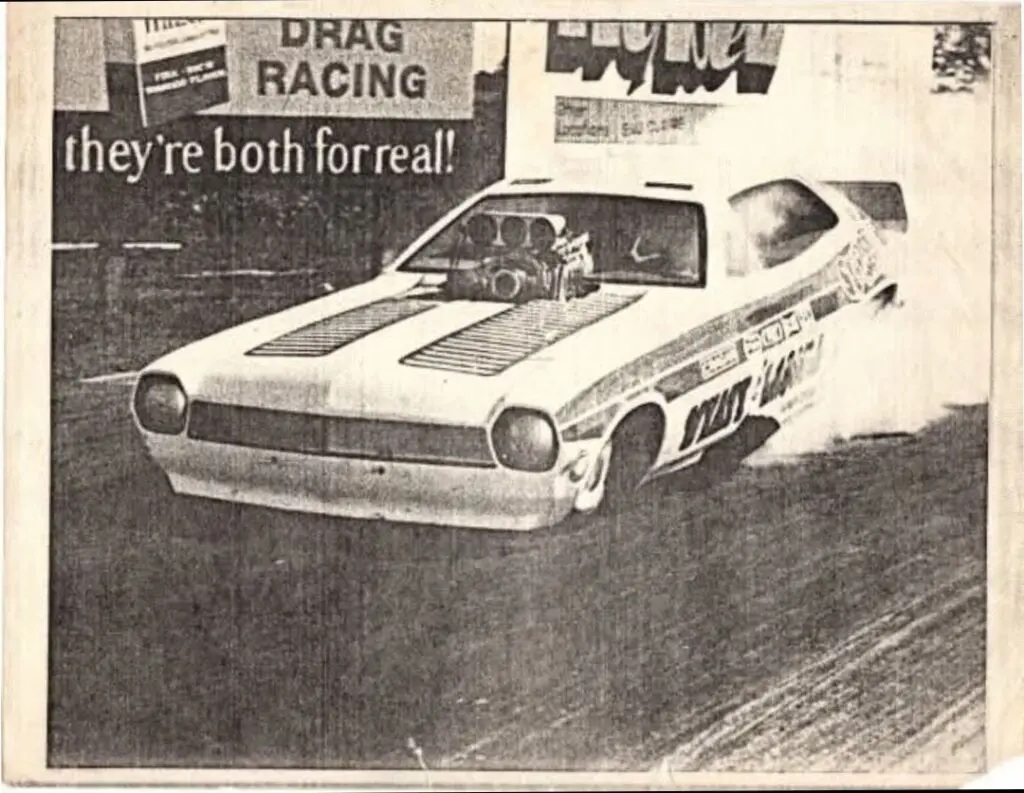

Wyatt’s path into Funny Car racing did not begin with nitro power or national aspirations. His entry came through a now-defunct class that required immediate adjustment before he ever made a competitive run.

“Well, I actually started out to build what was going to be an A/Fuel Funny Car because they ran them in UDRA back in the day, and about the time I got the thing finished, they’d done away with them and made them blown alcohol, so I switched to that and started running UDRA,” Wyatt said.

That transition led to a debut that left a lasting impression. Wyatt said the first time he raced the car, the magnitude of what he had taken on became immediately clear.

“The first time I ran it, it was one of them deals where you think, ‘Oh, I might have bitten off more than I could chew,’ because I was just a kid,” Wyatt said.

The location and circumstances of that debut elevated its significance. Wyatt’s licensing run took place at the World Series event at Cordova, Illinois, surrounded by names that defined the era.

“I did it at Cordova at the World Series, and I had Tommy Ivo, Vern Motes, Roger Gustin and Doug Rose sign off on my license, and I really wish I had the original one back,” Wyatt said.

Looking back now, Wyatt said the lessons he would pass along are rooted in realism rather than romance. Time has given him perspective on just how demanding the road would become.

“I’d tell him he needs to really be tough and thick-skinned, because if he’s planning on doing this, it was really, really a tough road,” Wyatt said.

Experience has also given Wyatt a sense of responsibility toward younger racers. He said he now tries to remove unnecessary obstacles that once felt unavoidable.

“I try to show the young guys that are even working on it an easier way of doing stuff and not make it so hard, but you still have to be tough and put up with a lot of sacrifices,” Wyatt said.

Despite the grind, Wyatt said he was never thin-skinned early in his career. Instead, he credits a combination of ambition and good fortune for helping him endure the learning curve.

“No, I really wasn’t, and I don’t think I was smart enough to be, to be honest with you,” Wyatt said. “I was really fortunate because guys could see that I had the ambition and really wanted to do it, and they helped me as much as they could.”

That support often came from seasoned veterans who saw something worth investing in. Wyatt said one of the most influential figures early on was Vern Moats.

“He really took a liking to me. He had a gruff demeanor, but he treated me really well, showed me stuff, sold me parts, and told me what I needed,” Wyatt said.

Wyatt also found guidance within UDRA competition through Jim Crownhart, whose influence extended beyond racing technique. The lessons were about lifestyle as much as performance.

“Jim took me under his wing, and I followed him. He showed me how to be a touring professional, how to drive from race to race, how to eat out of the cooler, and how to survive at the racetrack,” Wyatt said.

Those experiences prepared Wyatt for the next major shift in his career. When the time came to consider Nitro racing, he admitted he was starting from scratch.

“None at all,” Wyatt said when asked if he had any Nitro knowledge at the time.

That transition came through relationships rather than structured instruction. Time spent around alcohol teams introduced Wyatt to Tom and George Hoover, a connection that changed his trajectory.

“I told George Hoover I wanted to run Nitro, and he kind of joked about it at first, but then he told me I could do it and really helped me through switching into Nitro and going that route,” Wyatt said.

Unlike many drivers of his generation, Wyatt said he never framed his career around becoming a star. His goals were practical, rooted in sustainability rather than legacy.

“My ambition was just to go race and try to make a living at it. A lot of guys start out racing as a hobby, but my ambition was to race for a living,” Wyatt said.

That approach shaped how Wyatt viewed success. Championships and recognition were secondary to simply continuing to compete.

“Being a world champion was one of them things where if it happened, it happened. If it didn’t, as long as I could survive and go race the next race, that was good enough,” Wyatt said.

By the early 1990s, Wyatt had achieved that goal. After operating his own shop since he was 19, he stepped away to focus more heavily on racing.

“I said, ‘You know what, I’m just going to do it part-time, but I’m going to race,’ and we ran the whole tour in the early ’90s up through 2000, but it just got so expensive,” Wyatt said.

Rising costs eventually narrowed the path forward, but Wyatt continued through a combination of ingenuity and support. He said the formula was simple, if not easy.

“I found enough help through guys giving me parts, manufacturers helping me out, and finding small sponsorships to keep feeding the thing,” Wyatt said.

Only recently did Wyatt consider stepping away entirely. The decision was not driven by desire, but by the realities of modern racing economics.

“I was going to quit at the beginning of last year,” Wyatt said.

The re-emergence of IHRA provided a reason to continue. For Wyatt, it reopened a door he was prepared to close.

“IHRA came along and started that thing back up, and that gave me a reason to keep going,” Wyatt said.

Fifty years into a Funny Car career defined by adaptation rather than accolades, Wyatt remains guided by the same principle that carried him from his first license signing to his decision to keep racing today. “As long as I can survive and go race the next race, that’s always been good enough for me,” Wyatt said.

COMPETITION PLUS POWER HOUR MOVES TO NEW TIME, UPDATES FORMAT FOR 2026