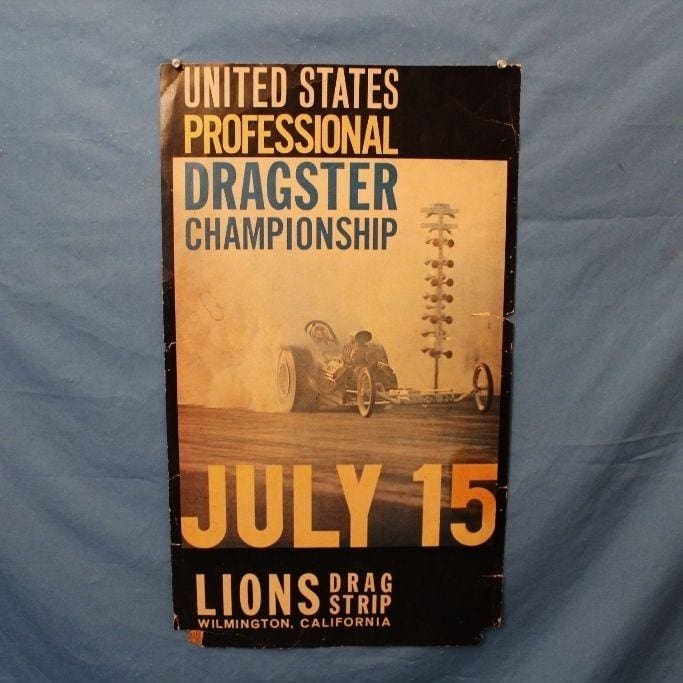

When fans paid their $5 general admission — plus another $2 for a pit pass — at Lion’s Drag Strip in 1967, they were stepping into what felt like a Mission Impossible scene brought to life. The sound of nitro engines blended with the thrill of something new — the debut of the Professional Dragster Association.

The PDA was the creation of Doug Kruse, a dragster body builder and promoter who believed that Top Fuel racers didn’t need the emerging Funny Car craze to fill grandstands. His bold idea: a one-day, 64-car Top Fuel shootout that would stretch deep into the California night.

Ninety-four cars showed up for that first PDA race, which combined qualifying and eliminations into one marathon session that didn’t end until 4 a.m. “The first PDA Meet in ’67 was all dragsters,” said Hall of Fame journalist Dave Wallace. “The idea was to show that we didn’t need those Funny Cars to sell seats.”

Kruse, Wallace recalled, was “a rabble-rouser and a smart guy, very educated.” He wasn’t just running an event; he was pushing back against the establishment. “He might’ve been the first president of the UDRA, the United Drag Racers Association,” Wallace said. “That was the most effective racer organization I ever witnessed, and they were tied closely together.”

The UDRA had formed earlier in the decade to demand bigger purses at Lions, the epicenter of Southern California drag racing. The PDA became an extension of that movement — racers taking control of their destiny. “Everything revolved around Lions in the early sixties,” Wallace said. “Kruse and the UDRA guys wanted to prove they could put on a better show than anyone.”

The 1967 event proved they could. Wallace remembered the field was loaded with talent and ambition, including an unexpected star from the East Coast. “These guys from D.C. came out of nowhere,” he said. “Bruce Wheeler had bought Ed Pink’s old master car with his inheritance, and they qualified number one for the first PDA Meet — above all those guys.”

Running qualifying and eliminations for 64 dragsters in one day was unheard of, yet it happened. “Imagine that — sixty-four cars in one day,” Wallace said. “It went till four in the morning.” Despite the chaos, the operation ran with remarkable speed, partly because of one key factor: no burnouts.

“There were no burnouts that I remember,” Wallace said. “That’s why the show could move. Two on the line, two pushing down, and two waiting to run — you could have six cars fired at all times, sometimes eight. Once the burnouts started, it slowed everything down.”x

Running qualifying and eliminations for 64 dragsters in one day was unheard of, yet it happened. “Imagine that — sixty-four cars in one day,” Wallace said. “It went till four in the morning.” Despite the chaos, the operation ran with remarkable speed, partly because of one key factor: no burnouts.

“There were no burnouts that I remember,” Wallace said. “That’s why the show could move. Two on the line, two pushing down, and two waiting to run — you could have six cars fired at all times, sometimes eight. Once the burnouts started, it slowed everything down.”

Efficiency was the secret ingredient. “As soon as they staged and cleared the finish line, the next cars were ready,” Wallace said. “That’s how places like San Fernando could have a three-hour show with Top Fuel, Top Gas, and comp-type cars all in one day.”

The first PDA race became a benchmark for how good independent drag racing could be. “That one set an attendance record for Lions,” Wallace recalled. “It was a big deal, really important.”

The event’s success led to expansion. Kruse later partnered with promoter Bill Doner, who brought PDA races to Orange County, Seattle, and other West Coast venues. “The first one at Lions was the big one,” Wallace said. “They had sixty-two cars for the first round of a sixty-four-car show. It was an amazing event.”

Wallace compared the PDA’s significance to another independent classic — the 1959 March Meet in Bakersfield, which helped launch the careers of stars like Don Garlits. “The ’59 March Meet was unbelievable,” Wallace said. “They had outhouses for 800 people and wound up with 30,000. It was right in NHRA’s backyard after Wally Parks banned fuel in ’57.”

Between rounds of racing, catch up with Billy Meyer as he shares some wild stories from when he drove a Nitro Funny Car!#DragRacingNews https://t.co/S3nydh3fFi

— Competition Plus (@competitionplus) October 11, 2025

Those two events — Bakersfield in 1959 and Lions in 1967 — marked the heart of drag racing’s independent rebellion. They showed that racers didn’t need sanctioning bodies or corporate polish to fill grandstands. They just needed nitro, grit, and a will to race until sunrise.

“The PDA was drag racing the way we grew up,” Wallace said. “Pure, fast, and for the racers.”

And when asked what made that 1967 Lions race so unforgettable, Wallace didn’t hesitate. He smiled and said, “It wasn’t pretty, it wasn’t polished — but by God, it was drag racing at its best.”