Originally published August 2007

RELATED LINK – PART 1 – THE EARLY YEARS

Photos courtesy of David McGee, Norman Blake, IHRA Media, Dave Bishop

In the early 80’s, the growing popularity of the IHRA mountain motor Pro Stock class made a huge ripple in the great drag racing pond – a ripple felt all the way past the front doors of NHRA headquarters in Glendora, Ca.

Headlines once reserved for Bob Glidden, Lee Shepherd, and Frank Iaconio now featured such names as Rickie Smith, Warren Johnson, and Ronnie Sox. The IHRA Pro Stockers had blasted their way into the 7.90s during the 1980 season and the 7.80s one year later.

Never mind the fact the NHRA had just staged the closest point championship in the history of the class, a battle that went down to the final run of the season. The IHRA had seven-second Pro Stockers and wasn’t afraid to flaunt them to the media.

NHRA cars ran 8.30s. IHRA cars ran 7.80s. Get the picture?

In the weeks prior to the end of the 1981 season, the NHRA announced that they would do away with the pounds-per-cubic-inch format and adopt an IHRA-type program.

Instead of the sky-is-the-limit mentality of the IHRA, however, the NHRA put a 500-inch ceiling on their “mountain motors.”

In many aspects, the IHRA had shamed the NHRA into adjusting their rules, which was a real PR coup for the junior circuit. This change made it possible for many of the real hitters, those who once ran exclusively in the NHRA, to have an option on where they raced.

The NHRA’s re-adjustment made it possible for Pro Stock teams to race all three major sanctions just as they had before IHRA’s decision to implement the mountain motors in 1977.

Pat Musi had successfully competed in all three sanctions in 1981 with the same car and fared well. However, he was the only one. The NHRA’s decision to follow the IHRA’s lead played well with most racers, but not with Musi. Musi was running the large motor in IHRA and AHRA, but would put the small motor in to run NHRA. Just as he found the right combination for the small motors, the NHRA changed their rules

“It was frustrating because I had just gotten my small motor program working real well when they decided to open it up to 500 inches,” Musi said. “Then I had to return to the big motors all over again.”

Musi decided it was a good time to take a break from racing.

While many didn’t feel the NHRA was shamed into the adjustment, most said their actions made the need clearly evident.

“I think it was the shame of seeing us so far ahead that pushed them into the 500-inch motors,” Rickie Smith, five time IHRA mountain motor pro stock champion, said.

Warren Johnson felt the NHRA made the most logical move at the time. The convergence of the rules put Johnson in a good position to return to the NHRA on a regular basis, while maintaining his status on the IHRA side.

Johnson’s engines were rarely larger than 500-inches.

“The NHRA was at the point they were pulling their hair out trying to keep things level in the factoring process,” Johnson said. “They were constantly adjusting on a weekly basis. Then you had the IHRA cars running consistently quicker. That created the stimulus for the NHRA to look at setting a common displacement of 500 and weight. It was smaller than the IHRA’s engine but a step up from the small block. It solved two problems, it got rid of the headaches and sped their cars up.”

Roy Hill said it was the excitement the IHRA had for their Pro Stock class that made the NHRA envious.

“I don’t think the NHRA was shamed into it, I just think they saw the excitement of the racing community and the media towards our cars,” Hill said. “It wasn’t as hard for them to maintain the class. I don’t think you ever really shame anyone into anything, people are going to do what they are going to do.”

RACING ON A PRO STOCK BUDGET

Prior to 1982, the IHRA’s mountain motor Pro Stock style of racing was a reasonably affordable means of racing professionally. Once the crossover began, the competition got stiffer and the price of winning even higher.

“You didn’t have .04 separating the field,” Musi said. “You had four tenths. Back in those days you had guys that ran on lower budget and didn’t really have 32 cars capable of winning at any given time.”

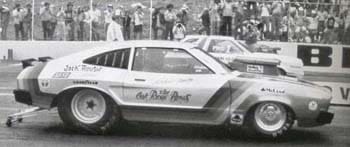

All of a sudden, instead of names like Johnson, Rickie Smith and Ronnie Sox (who were competitive champions in their own right), names like Lee Shepherd, Bob Glidden, and Frank Laconio were on the final qualifying lists.

Enter Reher-Morrison and their driver Lee Shepherd. Their presence in the IHRA community raised the level of competition. While many of the IHRA cars displaced engines in the 600-plus range, they remained closer to their NHRA combination.

“We really didn’t think they [the IHRA Pro Stockers] were that fast to be honest,” engine builder David Reher said. “We weren’t sure. When we put the 500-inch together, we knew they weren’t that fast. Our first time out, we set the E.T. record and then reset both in Gainesville.

“Then we decided to go to Darlington with the 500-inch motor and while we didn’t win, we ran fast. We came home and built a 540-inch motor – and that seemed small and worked up to 638 – before we quit running. I think we stepped up the pace of things over there.”

In the first outing for R-M-S, they ran a 7.84 with a 500-inch engine. Their clear domination immediately made them a favorite for not only race fans but the series sponsor as well.

“Rickie Smith was the first into the sevens but that was before we ever got there,” Reher said. “When we got there, we were usually about .15 quicker. It was fun, and back then [series sponsor] Winston used to take care of us and get us motel rooms and make sure we were there.”

“It made everyone have to go out and spend more money to have a chance to win,” Smith said of Reher’s appearance in IHRA.

Roy Hill said he remembered the RMS days and their raising of the competitive bar. A driver in the class from the first mountain motor event, Hill said it was a bar already in motion, the motion just got faster and pricier.

“By the 1980s, we were fortunate enough to have a car for each sanctioning body and that’s what became apparent that you would have to do to keep up,” Hill said. “You had to have two because you needed the one with the IHRA to have the motor slid back a few inches and raised up a little bit to handle the extra horsepower – 814 inches, world of difference from 500-inches.

Reher & Morrison gets the lion’s share of credit for advancing the class, but Hill advises that WJ deserves recognition as well.

“He just came out here and dominated things,” Hill said of Johnson, who won the 1979 and 1980 championships. “He ran hard and just did the right things. Warren made you run hard to have to try and beat him. That was before Lee Shepherd even got here.”

“When you got the guys in there like Reher & Morrison and Warren Johnson, it tightened the competition,” noted engine builder Sonny Leonard said. “A lot of people came up with innovative things. It wasn’t a follow the leader thing. You made your own way.”

THEY CALL HIM TRICKY

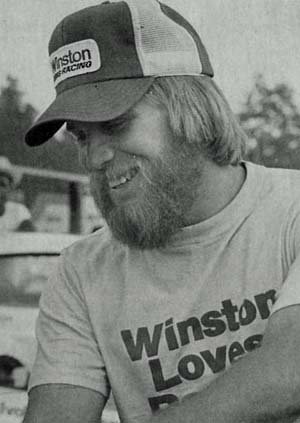

Ask Rickie Smith and he’ll tell you that he earned his championships the old fashioned way. While his opponents were comfortably tucked away in their hotel beds or bellying up to the bar, he was working.

At 3 AM, while others snored or did whatever, Smith was sprawled on the asphalt underneath a car – working. That’s what he did.

Smith heard the jeers and backbiting comments when he wore down the competition. He’d shake his head as he walked away. Smith was often heard to say, “Why should I apologize for working hard?”

Second-guessing and criticism were nothing new to Smith. He’d experienced that while running the IHRA heads-up and no breakout sportsman class called Super Modified.

His domination may have looked easy to the competition but reality dictated a different story.

“We didn’t keep the cars at the track back in those days,” Smith said. “We’d be on our backs in the parking lot of the hotel working on the cars on Friday and Saturday nights. Jack Roush will be my witness that back in those days we had a lot of bearing troubles to deal with. That was an every race thing until 1 and 2 o’clock working on the engine and checking bearings while the competition was out partying.

“Don’t get me wrong, I did my share of partying too, but I worked awful hard on my car to make sure it didn’t break during eliminations. If you look back throughout my career, I hardly ever gave away rounds because of breakage. I watched out for the little stuff and that was the attitude I brought into this class.”

Smith worked his way into a winning machine. In fact, Smith won so many Super Modified races in 1977 (winning 7 out of 10 events) that IHRA, seeing a lack of interest and participation based on Smith’s success, cancelled the class.

That should have been an adequate wake-up call for the Pro Stock class when Smith and team owner Keith Fowler announced intentions to go Pro Stock racing. But, it didn’t.

They were too busy trying to catch “General” Lee Edwards.

Musi finished runner-up to Edward for two consecutive seasons and readily admits that Smith didn’t make it on his radar.

“I really didn’t give it much thought that he’d build the reputation he has today,” Musi said. “But he stayed after it. He had some good sponsors and just got after it.”

Fowler’s dislike of brake-light racing was the deciding factor that pushed Smith into Pro Stock.

“I was racing in a 1969 Camaro before Super Modified came along and Keith could never understand the breakout thing,” Smith said. “I would come to him and ask for more money to go faster and he would ask me why I needed to go faster when we would lose for breaking out. Pro Stock made it simpler for him.”

In those early days, if Smith couldn’t outperform you on the track, he’d lure you into his game of starting line antics. That’s where he earned the nickname “Tricky” Rickie.

Make no bones about it; if Smith had his druthers, he would prefer to beat your socks off in performance.

“It was a lot of hard work,” Smith said. “I worked night and day. A lot of the other guys wanted to do it as a hobby. That’s how Glidden got so good on the NHRA side; he treated it like a business and not a hobby. I was his IHRA equivalent. I worked at it full time.”

Smith said many sacrifices were made in the early years of his career just to race. That’s why he fights to the bitter end in every competition.

For Smith, his drive for legendary status was a costly one, the lost moments don’t compare to his Pro Stock record of 53 final rounds resulting in 31 victories.

“I worked at it hard and lost a lot of time with my kids,” Smith said. “I gave up a lot of my personal time to win those championships. You don’t realize that until you get old and see what you gave up. I can’t say that I would have done it different even though I know better now. Some moments you’ll never get back in life.

“I just look back at all the stuff I ever did in my life,” Smith said. “And when I get to the chapter in the mountain motor Pro Stock racing, I am blown away at the good fortunes that came my way. It’s more than you can ever imagine.

“I think we all have a purpose in life and for me it was mountain motor racing. The IHRA gave me a place to prove myself back in those early days. I can’t think of a better place for it to have started than in the IHRA. I was just glad that this was my destiny and the IHRA’s too. I guess we all got famous together.”