There is nothing more prestigious than winning Top Fuel at the NHRA U.S. Nationals, and that stage is exactly what a group of sportsman racers used in 1981 to mount a protest.

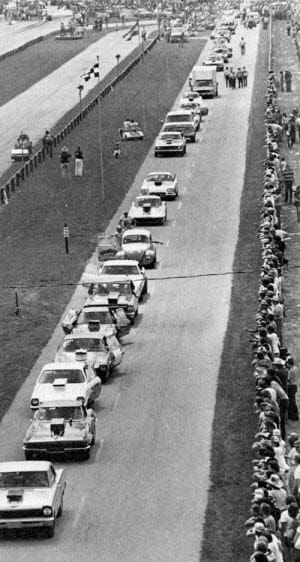

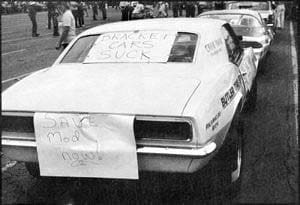

As nitro dragsters thundered down the Indianapolis Raceway Park quarter mile on Labor Day weekend, more than 100 Modified Eliminator competitors staged a parade down the return road in front of a packed grandstand. Their message was clear: they would not go quietly as NHRA disbanded their beloved eliminator.

The decision, announced earlier that year, divided Modified classes between Competition and Super Stock Eliminators. For racers who had spent years perfecting high-winding doorslammers, the move felt like an erasure of identity.

Modified Eliminator combined Gassers, Modified Production, Super Modified and other small-tire combinations. It was a category for innovation and driver skill, drawing a loyal fan base. By 1981, NHRA argued the eliminator lacked strong local participation, particularly on the West Coast. National events, however, often saw more than 100 entries, with 148 cars showing up at that year’s U.S. Nationals. For many racers, NHRA’s reasoning rang hollow.

According to CompetitionPlus.com’s 2007 article, “The Day the Sportsman Fought Back,” the protest had been whispered about for months. Racers knew their only chance to be heard was to demonstrate on drag racing’s biggest stage.

Instead of shutting down racing, which would have led to expulsions, racers settled on a parade. Chevy IIs, Corvettes, Fairmonts, Camaros, Mavericks, even Volkswagens — they all rolled in single file past the grandstands. Many fans were confused, but they knew something unusual was happening.

Mike Keener, who along with Paul Mercure fielded the respected Checkmate team, was one of 125 qualifiers who joined the demonstration. “The word just filtered down to us from the NHRA,” Keener said in the 2007 article. “At first we dismissed it as rumor, but as the season continued, we began to hear it more and more. We finally realized that it had to be true. That’s when the ‘Save Modified’ buttons were distributed to everyone. It was a pretty disruptive time and a lot of guys were upset.”

Keener admitted the protest did little to change NHRA’s stance. “It was just a big show of support for all of the racers on behalf of their class and the fans of Modified who were very dissatisfied with the NHRA’s decision to end the class. We didn’t want to go into Competition Eliminator.”

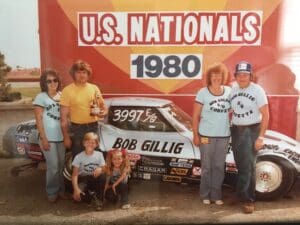

Bob Gillig, a Modified Production racer who later became an IHRA Pro Stock crew chief, remembered that the protest could have been more disruptive. “The original idea was to drive the cars down the track in protest,” Gillig said in the 2007 CompetitionPlus.com piece. “The NHRA came to us and let us know in no uncertain terms if we drove onto the track and stopped the race that we’d all be escorted out of there. They gave us the option of the return road.”

Gillig, whose career later spanned crew chief roles in Pro Stock, died in March 2025. His reflections stand as part of the defining oral history of the Modified Eliminator protest. “The way they looked at it, they were God and what we had to say didn’t matter,” Gillig also said in 2007. “If you wanted to race, you had to play by their rules.”

Paul Mercure recalled that racers believed they were doing the right thing. “Now I know otherwise,” he said in the CompetitionPlus.com story. “Back then we thought we were doing the right thing. The NHRA never said a thing to us, but gave us some dirty looks. I really think the same thing is getting ready to happen to Competition Eliminator.”

The final chapter for Modified Eliminator came at the close of 1981. Faster classes such as Modified Production and Gas Coupes were moved into Competition Eliminator, while slower classes went to Super Stock. For many, the blending diluted the identity of Modified racing.

Mike Edwards, who became the last Modified Eliminator world champion in 1981, said he remembered the protest clearly. “We were just trying to stand up for our class,” Edwards said in 2007. “We loved the class and it was special for each one of us. That’s where my roots are. We didn’t prevail, but it couldn’t take away the love I had for it.”

Edwards said Modified meant more to fans than the categories it was folded into. “I hated to see it die,” he said. “When I was growing up I learned to race in that class. Some people aspired to run Pro Stock, but for me it was Modified Eliminator. I think Modified got more notoriety than the classes that it was broken up and put into. The real racing fans understood Modified.”

.

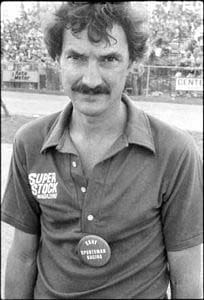

NHRA’s in-house publication, National DRAGSTER, never mentioned the protest. Independent magazines like Super Stock & Drag Illustrated and Hot Rod carried the story. Freelance journalist Dave Wallace, covering the U.S. Nationals for Hot Rod, said the racers knew Indy was their one chance.

“They felt there was a chance to change some minds because essentially the whole drag racing industry congregated at Indy,” Wallace recalled in 2007. “This would be their only shot. I think it was a rare uprising against the establishment. The NHRA had never been challenged in a public forum like that.”

Wallace noted that the protest may have hurt the racers’ chances. “Whatever slim chance might’ve existed for saving the eliminator went away that day,” he said.

For many, the demise of Modified Eliminator signaled a changing of the guard in sportsman racing. Bracket racing was on the rise, and NHRA’s priorities were shifting.

Mercure said racers realized quickly that NHRA had the final say. “They were going to structure the sanctioning body the way they wanted to and you could either play by their rules or not play at all,” he said. “Many of us adapted and there were others that just quit. I don’t think it was ever the same for the high-rpm doorslammer cars.”

Even decades later, Keener said he thought often of Modified. “I wish it was still here. It was an exciting eliminator,” he said in 2007. “With today’s money and the cost of a high-rpm motor about $75,000–$80,000, it’s just not feasible. But that doesn’t mean we can’t miss it. We miss it a lot.”

Edwards agreed, calling it part of drag racing’s evolution. “It’s just another example of how the sport grows and keeps going on,” he said. “We thought it was the right thing to do and we did it.”

Those such as Gillig admitted that the local Modified participation had dwindled as the NHRA had alleged. Even he could see that there were fewer places to run Modified at the end than there had been when he started. “Most of the tracks had switched over to bracket racing,” Gillig said. “Those guys at the local tracks were itching to run national events. They were always quick to say ‘beat me and not my wallet.’ The bottom line is that half of those guys couldn’t shift a stick and they drove like little old ladies. That slowed them down. They went to automatics. We just didn’t want to go to that.”

Dave Wallace, covering the event for Hot Rod, said the demonstration was both bold and doomed. “They (Modified racers) were going around cars that had just finished racing, coming back down the return road. The other racers were clapping for the Modified teams. I think it was real ballsy, but the downside of it was that whatever slim chance might’ve existed for saving the eliminator went away that day. It didn’t really generate any new support, but it may have worked as a negative.”

In the end, it was the late Steve Collison, longtime editor of Super Stock & Drag Illustrated, who wrote the epitaph for the class. Covering the final Modified Eliminator event at Indy, he said, “Modified at Indy took on an entirely new meaning because, in light of NHRA’s decision to break up the eliminator between Comp and Super Stock for 1982, there would never, EVER be another Modified race like this one. And to anyone who appreciates the personal efforts and technological achievements that go into these gear-stompin’, wheel-hoppin’ quarter-mile race cars, the loss of their identity is truly a sad state of affairs.”

His words, first published in 1981, still ring true more than four decades later. For the racers who lined the return road that day, it was a statement that their class mattered — even if NHRA never changed course.