Whoever knew that a post-war fascination with mechanical innovation in construction and drag racing would lead to hobnobbing with Hollywood headliners?

Such is the history of Ty-Rods and New England Hot Rod Hall of Famer Loyed Woodland.

Loyed Woodland (left) recently donated his archive of photos, news accounts, his Nomex coveralls, and other memorabilia to the Don Garlits Drag Racing Museum at Ocala, Fla. Garlits greets the New England Hot Rod Hall of Fame member. (Photo courtesy of Gordon Daniels) Whoever knew that a post-war fascination with mechanical innovation in construction and drag racing would lead to hobnobbing with Hollywood headliners?

Loyed Woodland (left) recently donated his archive of photos, news accounts, his Nomex coveralls, and other memorabilia to the Don Garlits Drag Racing Museum at Ocala, Fla. Garlits greets the New England Hot Rod Hall of Fame member. (Photo courtesy of Gordon Daniels) Whoever knew that a post-war fascination with mechanical innovation in construction and drag racing would lead to hobnobbing with Hollywood headliners?

Such is the history of Ty-Rods and New England Hot Rod Hall of Famer Loyed Woodland.

The NHRA’s return to the Northeast for another Countdown event, at Reading Pa., invokes memories of record-setting performances, most recently from Antron Brown, Shawn Langdon, Andrew Hines, and Frank Manzo. Maple Grove Raceway has produced the quickest and fastest passes in NHRA history and five of the fastest eight.

But back in the 1960s, when muscle cars were the rage – along with TV and TV dinners, hula hoops and Slinkys, and Elvis – Boston-area kingpins Woodland and Bob Andresen, his racing and business partner, ruled the region’s dragstrips. They won championships, set records, and intimidated the competition first in their Brainbeau Oldsmobile and later their Berejik Oldsmobile stocker and, for a three-year stint, the Smothers Brothers.

And thanks to invaluable help from longtime friend David Keith, Woodland recently donated his archive of photos, news accounts, his Nomex coveralls, and other memorabilia to the Don Garlits Drag Racing Museum at Ocala, Fla.

What drag racing fans could learn from the faded clippings are details of the New England championships Woodland earned between 1955 and 1960 with his Oldsmobile-powered roadsters and coupes. They could read about his unique partnership with the late Andresen that lasted on the track from 1960 until 1971 and in business until Andresen’s death in 1995. Fans could read about the multiple class records – 10 national records — the two set in C, D, and F Stock at Sanford, Maine; York, Pa. (U.S. 30 Drag-O-Way); Quebec’s Napierville Dragway; and Crofton, Md. (Capitol Raceway).

They might browse through accounts of Andresen’s custom-milled parts and bespoke tools that benefited not just Woodland on the racetrack but also General Motors as it improved its line of Oldsmobile production cars.

(Thanks to Andresen’s suggestions, the automaker made lasting changes to specs for camshafts, valve springs, compression ratio, manifolds, auxiliary batteries, and the transmission linkage system. In the early stages, Andresen received wind-tunnel / air duct help from Bob Tasca Sr., of Tasca Ford.)

But between the lines lies the story of a remarkable partnership that endured the pressures of competitive drag racing and perhaps the even more cutthroat paving and construction industry.

Woodland and Andresen had become acquainted as they “Cruised the Drag” (Main Street in Brockton, Mass.), Woodland in his channeled ’32 Ford deuce coupe, Andresen in his full-fendered ’34 Ford coupe.

Even before Woodland joined forces with Andresen to campaign a blown B Gas dragster in 1960, the latter had gained a reputation for tricking out his race cars with proprietary parts he had designed and milled himself. By 1965, the two had transitioned to stock hot rods – in Woodland’s words, “to prove the Oldsmobile engine could be competitive in any class.”

Their famous Brainbeau Olds sponsorship never would have happened were it not for the persistence and networking of Ray Kaligian, a salesman at the dealership who knew of Woodland and Andresen and their skills.

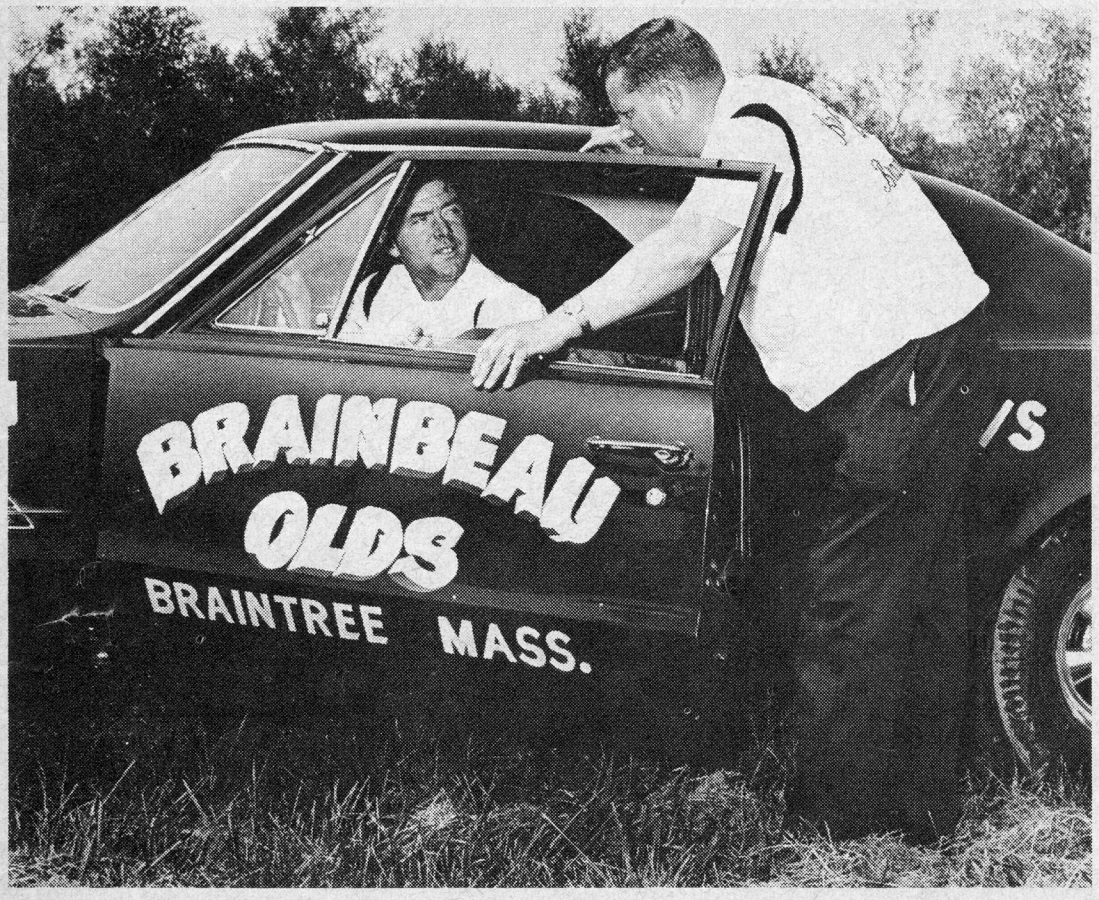

Loyed Woodland (in car) and crew chief Bob Andresen plan strategy for their next pass down the dragstrip in this photo that appeared in the January 1967 issue of Super Stock & Drag Illustrated magazine. (Photo courtesy of Loyed Woodland and Gene Horn) Oldsmobile built the first 442 (which stood for four-barrel carburetor, four-speed transmission, and dual exhaust) in 1964. Through his series of acquaintances, Kaligian learned that Oldsmobile was interested in running a drag-racing stock car to rival the Pontiac. His contacts in Lansing asked if he would be interested in the program. Kaligian immediately turned to Woodland, whom he described as “sort of the idol” around their hometown of Brockton, Mass., and a “very, very capable” individual. Andresen, Kaligan said, “was a very intelligent guy, very quiet, very authoritative. When he said something you knew what he was talking about.”

Loyed Woodland (in car) and crew chief Bob Andresen plan strategy for their next pass down the dragstrip in this photo that appeared in the January 1967 issue of Super Stock & Drag Illustrated magazine. (Photo courtesy of Loyed Woodland and Gene Horn) Oldsmobile built the first 442 (which stood for four-barrel carburetor, four-speed transmission, and dual exhaust) in 1964. Through his series of acquaintances, Kaligian learned that Oldsmobile was interested in running a drag-racing stock car to rival the Pontiac. His contacts in Lansing asked if he would be interested in the program. Kaligian immediately turned to Woodland, whom he described as “sort of the idol” around their hometown of Brockton, Mass., and a “very, very capable” individual. Andresen, Kaligan said, “was a very intelligent guy, very quiet, very authoritative. When he said something you knew what he was talking about.”

Kaligian suggested to John Thibeau, who owned the Brainbeau Olds store at Braintree, Mass., that sponsoring a car at the popular drag races would enhance sales. But in Kaligian’s words, Thibeau was “completely dead against doing anything like that.” Thibeau, he said, painted the proposal as “nothing more than throwing money away.”

Kaligian assured Thibeau, “They’re not run-of-the-mill kids who are driving ridiculously through town. They know what they’re doing.” With that Kaligian arranged a meeting between his boss and the racers, and he said Thibeau “decided to let us go forward.”

Then came an invitation to Lansing, and the three boys from Boston (Kaligian, Woodland, and Andresen) met with John Beltz, chief engineer for General Motors’ Oldsmobile division and engineer Dale Smith, who had been charged with spearheading the 442 project. They were obliged to meet in secret, because GM had a racing ban in place at the time.

Once they got rolling with the successful Brainbeau Olds, Woodland said he received a call from a GM executive he called a “dumb s—t” who warned him he could be in trouble for violating GM’s racing ban.

The feisty Woodland said he told the GM representative he was not “not afraid of getting into trouble unless a pinhead like him would squeal to the head of General Motors. I told him, ‘The bottom line on why you, me, or anyone else here exists is to sell cars. I’m trying to improve Olds’ youth image and cultivate new customers. If you can’t understand that concept, you might as well p— in your whiskey.’ ”

The Woodland-Andresen team raced on and steamrolled the competition in the Brainbeau 442. They won the New England championship right out of the box with their four-speed entry. “After awhile,” Kaligian said, “it got so that we couldn’t find any competition. So we switched over to an automatic and won a New England championship with that, too.”

One outing, in upstate New York, was telling.

“We purposely stayed quite a way away from the racetrack. Word was out that Brainbeau was going to be around. When we got there the next morning to the track, the field had 54 cars entered in the class. We showed up, and it ended up being 16 or 17. All the rest had fallen out. They didn’t want any part of it,” Kaligian said, still laughing at the memory as he reminisced from his home in New Hampshire.

Thibeau, though Woodland called him “a great sponsor,” remained skeptical about the connection between racing and sales – and wasn’t ever enamored of the 442 that pushed the brand from its slightly stodgy image, even though Brainbeau Olds sold many 442s. He told Kaligian he was annoyed the store had “so many of those damn high-priced cars.” Kaligian said, “I think they were $3,700 at the time. And it didn’t take long to sell them.”

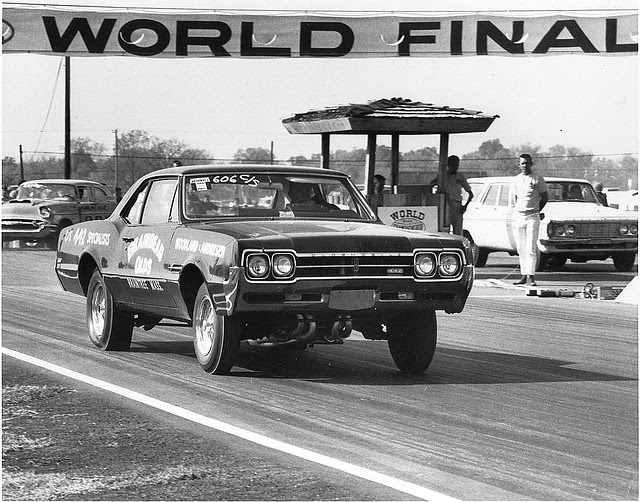

The Woodland-Andresen team were ambassadors for the Oldsmobile 442. This photo of Woodland was published in the June 1968 issue of American Rodding magazine. (Photo courtesy of Gene Horn)Woodland then won the 1966 NHRA U.S. Nationals. He lost on the track to his Pontiac GTO nemesis, Bob Gaudreau. However, post-race inspection discovered illegal parts on Gaudreau’s car and Woodland was declared the winner.

The Woodland-Andresen team were ambassadors for the Oldsmobile 442. This photo of Woodland was published in the June 1968 issue of American Rodding magazine. (Photo courtesy of Gene Horn)Woodland then won the 1966 NHRA U.S. Nationals. He lost on the track to his Pontiac GTO nemesis, Bob Gaudreau. However, post-race inspection discovered illegal parts on Gaudreau’s car and Woodland was declared the winner.

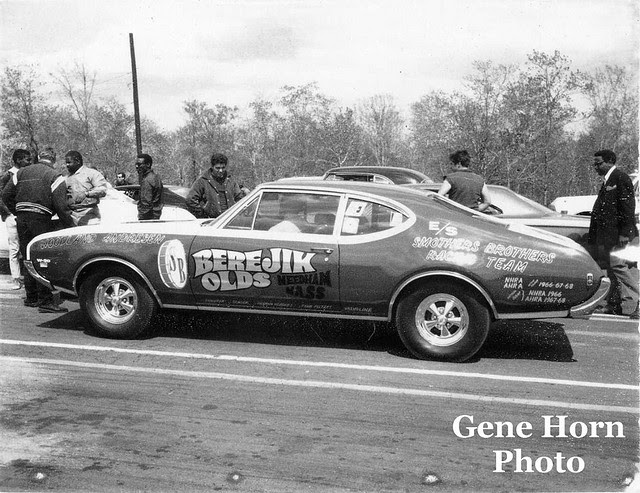

Shortly afterward, Brainbeau Olds went bankrupt – “not because of racing but because of misadventures of the dealer,” Kaligian said. From there, Kaligian went to work for Berejik Oldsmobile at Needham, Mass. There he pitched the Woodland-Andresen drag-racing team sponsorship to owner Tony Berejik, who like Thibeau, was a tough fellow to convince. But George Berejik, Tony’s son who often in his youth had taken the dealership inventory out for some illegal street racing, was all in for a race team. And Dad relented, and in 1968, the Berejik Olds race team picked up where the Brainbeau-sponsored operation left off.

“I don’t think it was his love for drag racing as much as it was for safety. He said, ‘Look, if I put together a racing team, would you get off the street?” George Berejik said in retrospect. But George was in the high cotton: “I couldn’t drive, but I could go watch my car on the track.”

And he said the Woodland-Andresen Berejik Olds 442 sponsorship paid off. “Absolutely. Monday morning the phone would be ringing right away: ‘Do you have a red 442?’ ‘Do you have a green 442?’ “Bench seat?’ ‘Bucket seat?’ It really boosted our business, all of our business,” George Berejik said. “It was really profitable. It compounded into many sales. Other Oldsmobile dealers who did not race fed off our success on the track. Other Oldsmobile dealers who didn’t specialize in 442s also benefited.”

Kaligian confirmed that. “It was during the Vietnam War. I used to get letters from these U.S. servicemen, saying they’d read about the race car and ‘When I get out of the service I’m going to buy a car from Brainbeau Olds or Berejik Olds. I want to meet Loyed and Bob.’ It was surprising how many of these fellows followed the car.” He corresponded with one service member from New Jersey and was particularly rocked by news that the young man had been killed in combat. “It’s more than just racing. It’s meeting people,” Kaligian said.

But George Berejik loved Woodland and Andresen with overwhelming enthusiasm. And the idea of the store sponsoring a car was beyond exciting to him.

“A lot of the dealers, with all due respect, were old-fashioned. They wouldn’t give any consideration to a 442. They needed a push, because Oldsmobiles were known as middle-of-the-road cars. You could buy luxury and you could buy power, but the majority of the Oldsmobile buyers went to the luxury side. We needed more people interested in buying the hot-rod side of Olds. Pontiac and Chevrolet were the race-car divisions. Oldsmobile and Buick were the middle, and Cadillac was the luxury division,” he said.

He was ready to freshen the medallion’s image, although the result was that “we fought more Pontiac dealers than we did anything else. It created competition [for GM] within itself,” he said.

How delicious was that, that George Berejik’s hobby brought in extra revenue for his father’s dealership? The younger Berejik was in Muscle Car Heaven. And he marveled at Woodland and Andresen.

“It was just a click that worked,” Berejik said of the pair of opposites. He acknowledged that across the decades he has discovered that “it’s hard to find that compatibility. They were even closer than brothers. Day and night, they were always together. To get all of that in one package is very rare.”

Woodland credited their quest for excellence. “We were both looking for perfection, and as an end result, we were always working as a team. We were equal, two minds that had the right power ingredients to create the world’s best-working engines and machines.

“We made decisions together. It wasn’t something that just he or I did. We always were close. It just worked good. We were good. He was smart about engineering. I was the one in the real world. We admired each other as innovators.”

Berejik chuckled at Woodland’s and the late Andresen’s yin-yang personalities but said, “The combination of these guys together was totally brilliant.

“Bobby was conservative and brilliant,” Berejik said. “Ohmygod, was that guy brilliant! If he did not have a part or a tool, he would make it. Incredibly brilliant. You cannot imagine how smart this guy was. He was off the walls with brilliance.”

Woodland, agreed Berejik and Kaligian (and even Woodland, who proudly said, “I was a cocky little bastard”), was the high-spirited one.

“Woody was loud, boisterous, and arrogant,” Berejik said. “One way or another, if you said no to him, by the end of the conversation, you were saying maybe or yes. He could persuade you into just about everything.

When Brainbeau Oldsmobile went out of business, Kaligian brokered a sponsorship arrangement with Needham, Mass., dealership Berejik Oldsmobile, and the Woodland-Andresen team kept rolling.

When Brainbeau Oldsmobile went out of business, Kaligian brokered a sponsorship arrangement with Needham, Mass., dealership Berejik Oldsmobile, and the Woodland-Andresen team kept rolling.

Later the pair raced under the Smothers Brothers banner, with funding from TV and recording celebrities Tommy and Dickie Smothers. “Right from the get-go, and justifiably so, he was very cocky. He knew how to drive. He knew what to do. He knew how to get it done. He came with lots and lots of confidence. To convince my father – who was very, very conservative – to start a racing team, it took a lot,” he said. “It was great for me. I loved racing and hot rodding. I was very shocked that they got my father to say yes. I guess his cockiness was his biggest attribute, although he could drive – there was no question about that. He was one of the best drivers there was and a pretty good mechanic on top of it. Between Bobby and Woody, they convinced him to do it.”

But it was Berejik who influenced the decision to hook up with the popular musical comedy duo The Smothers Brothers, who drag-raced an Oldsmobile.

Tony Berejik met the celebrities at Indianapolis, although he had no idea who they were beyond some guys who raced an Oldsmobile. He was wandering the pits and spotted the Smothers team. He asked if he could help them out, explaining, “I race a car out of Boston, Mass. We just got eliminated. My crew’s standing around, doing nothing, and I’d like to see an Oldsmobile win. If you need guys some help, I’d love to send them over.” The Berejik crew pitched in, and even Tony Berejik serviced the tires.

A couple of weeks later, George Berejik said, he got a call from the Smothers Brothers via their friend, Goldie Hawn. After conceding he wasn’t being pranked, Berejik realized the Woodland-Andresen team was one of five regional teams – the five fastest Oldsmobiles in the U.S. – the Hollywood stars were courting to race under their umbrella. So from 1969 through 1971, the Berejik Olds carried Smothers Brothers livery.

“Phenomenal experience,” George Berejik said. But Kaligian was opposed to the alliance and ended up taking a back seat thereafter.

“I was completely against it,” Kaligian said. He told Berejik, “You forget the intent of having a race car at the drags with your name on it. It was to promote Barijek Oldsmobile, just as it promoted Brainbeau Oldsmobile. I think you’re doing the wrong thing. If you’re going to sponsor a car, why would you have somebody else’s name on it?”

Said Kaligian, “I just bowed out and they ran it for a couple more years.” Berejik said the Smothers Brothers “lost interest. They said it was a good run and that they had fun. But it’s over now. It all seemed to fall apart in 1972.”

Woodland, proud of his “dedication to Oldsmobile and records,” called Oldsmobile’s dumping of the 442 “the worst day” and blamed GM for “poor management.”

In reality, the main factor in Oldsmobile’s about-face was the cutthroat competition between Chevrolet and Oldsmobile for the performance and racing share of the market, which traditionally belonged by default to Chevrolet. The vice-president in charge of Chevrolet lobbied GM’s president to kill Oldsmobile’s racing program, forcing the Dynamic Duo’s retirement from racing in 1972. The nation’s energy crisis and its financial impact, moreover, made their decision inevitable.

Before that, Woodland said, Oldsmobile had contacted them, offering them support to field an NHRA Pro Stock entry. He said they declined the offer but later regretted it. He gave kudos to Warren Johnson for his success that soon crescendoed and said, “If we had continued, Bob would have become one of the most sought-after crew chiefs in racing.”

Andresen continued as a consultant to Oldsmobile regarding its engine blocks, and both he and Woodland helped with Olds’ requests as it developed a quick-directional change for use in police cars.

After the racing team broke up, Woodland and Andresen turned their considerable energies to the asphalt paving business and the reclamation aspect of they pioneered.

The Boston-area dynamic duo of Bob Andresen (left) and Loyed Woodland lived by the popular “Win on Sunday – Sell on Monday” motto when they raced their Berejik Olds. (Courtesy of Brian Andresen)“They were the first ones to develop an asphalt reclaiming system,” Kaligian said. “It was nothing more than a horrendously large rototiller. Loyed built several of them. At one time, it had five diesel engines to operate it. Caterpillar and two or three other companies make these machines now, but they were the ones who developed it.”

The Boston-area dynamic duo of Bob Andresen (left) and Loyed Woodland lived by the popular “Win on Sunday – Sell on Monday” motto when they raced their Berejik Olds. (Courtesy of Brian Andresen)“They were the first ones to develop an asphalt reclaiming system,” Kaligian said. “It was nothing more than a horrendously large rototiller. Loyed built several of them. At one time, it had five diesel engines to operate it. Caterpillar and two or three other companies make these machines now, but they were the ones who developed it.”

“They were the first ones to develop an asphalt reclamation system,” Kaligian said. “It was nothing more than a horrendously large rototiller. Loyed built several of them. At one time, it had five diesel engines to operate it.”

Woodland found the largest of those diesel engines in Alaska, where it had powered the “Tundra Train,” a huge, rubber-tired land locomotive that used diesel-electric power for its 10-foot wheels. This “Tundra Train” was a long line of trailers laden with materials for building the Cold War’s DEW (Distant Early Warning) radar network across the Canadian Arctic. (Four of these giant wheels remain on one of the earliest “monster trucks,” parked today between a hotel and Interstate 4 in Orlando.)

“Caterpillar and two or three other companies make the pavement-milling machines now, but Woodland and Andresen were the pioneers who invented and developed it,” Kaligian said.

Said Woodland, “This is the most popular roadway recycling process in the world and was started in Bob’s barn in Brockton, Mass.”

Kaligian said after Woodland and Andresen sank all their assets into the development of this system and its machines, including mortgaging their homes, they couldn’t afford the considerable process in those days of acquiring a patent for their work.

That venture, like racing, was not without its intense rivalries.

“We built the machines and I actually made the specifications for my machine and no one else could use it. Sad part of the whole thing is that asphalt people were upset about us,” Woodland said. His competition, he said, “firebombed my pick-up at my house, and then they destroyed my office. It was interesting. Lori, my daughter, and I looked out at four o’clock in the morning. They filled it up with about 14 inches of water, the whole thing. All my specifications – everything – were destroyed. This was at four o’clock in the morning.”

He fought to get the door open. “I pushed hard against the door jamb, and it opened up. And all the water came 15 feet away from the door,” he said, describing being swept by the surge. “Imagine all this at four o’clock in the morning.”

Woodand scrapped with his competitors. But soon Andresen’s health began to fail. During a boating outing with wife Geraldine and Bob and Arlene Andresen, Woodand said he saw “the old Bob coming back” when he proposed their next enterprise: pothole patching. Andresen agreed to partner with Woodland again, but he died a week later from a brain aneurysm.

Woodland threw his effort into his revolutionary Pothole Medic technique for patching potholes permanently. It uses a high-velocity spray injection that protects the operator seated in a cab, holds traffic tie-up to a minimum, and is environmentally conscious.

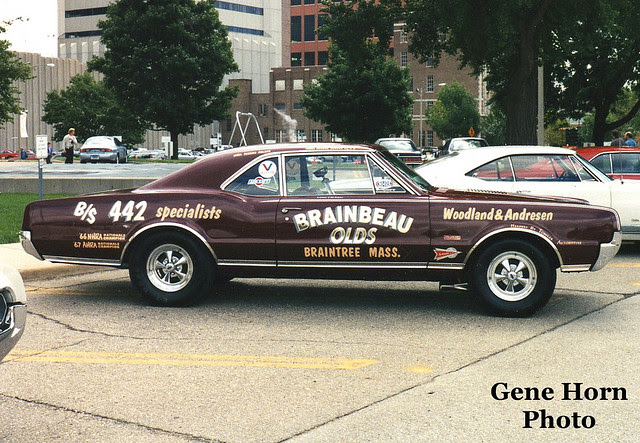

The Brainbeau Olds looked distinctive on or off the racetrack. (Photo courtesy of Gene Horn)“Instead of a guy or two or three guys out there putting some asphalt down [that] just falls apart again, this thing here, the guy’s in the truck, and it does everything from inside. There’s nobody in the street, on the road. So it’s very safe. It sticks right,” Woodland said, “and what it does is it compacts from the bottom up. It’s the best pothole patching in the world. This machine, it’s the best out there, and I spent some time making it better.”

The Brainbeau Olds looked distinctive on or off the racetrack. (Photo courtesy of Gene Horn)“Instead of a guy or two or three guys out there putting some asphalt down [that] just falls apart again, this thing here, the guy’s in the truck, and it does everything from inside. There’s nobody in the street, on the road. So it’s very safe. It sticks right,” Woodland said, “and what it does is it compacts from the bottom up. It’s the best pothole patching in the world. This machine, it’s the best out there, and I spent some time making it better.”

He said he fixed 13,500 patches in Massachusetts and Rhode Island alone – and, he said defiantly, “none of them fell apart.”

Triumphant still, Woodland spends these days at his Fort Pierce, Fla., home, recovering from a 2009 stroke. Occasionally he struggles to use the correct word. But he knows the word, just as he knows all the details of what and Andresen accomplished. He can recite his memories, and he said, “There have been some bad times, and there have been some good times – let’s put it that way.”

And his donation to the Garlits Museum was a chance “for all of us to consider and recognize the pioneers of our great sport of drag racing before it’s too late.”

George Berejik, whose dad passed away and who saw the dealership shutter its doors in 2004 with the death of GM’s Oldsmobile division, lives on Cape Cod today and speaks robustly despite continuing to battle a cancer diagnosis. Of those Woodland-Andresen drag-racing days, he said, “It was a lot of fun. I can’t tell you how much. Other than [being with] my family, it was the best time of my life, when we got into racing with those two guys.”

For Woodland, “it was just like a circus. It was a wonderful time I had. A lot of them communicate with me all the time. We had a good time. And we were successful. A lot of people call me and talk about the olden days. It’s just wonderful,” he said.