NHRA founder and drag racing godfather Wally Parks suggested in 1984 to shorten the iconic distance of 1320 feet to 1,000 feet or shorter. At the time, speeds were into the 260-mile per hour range and didn’t appear to be slowing down.

NHRA founder and drag racing godfather Wally Parks suggested in 1984 to shorten the iconic distance of 1320 feet to 1,000 feet or shorter. At the time, speeds were into the 260-mile per hour range and didn’t appear to be slowing down.

It appeared Parks’ suggestion was as blasphemous as the banning of nitro in the 1960s.

But, multiple sources have confirmed this wasn’t Parks’ idea at all. Instead, it was a strong suggestion handed down by the insurance companies as both Top Fuel and Funny Car divisions had breached the 260 mph barrier earlier in 1984.

NHRA, before making a change, did their due diligence in studying how much a move to 1,000 feet would slow the nitro cars down. They set up timers for the 1,000-foot at the 1984 NHRA U.S. Nationals and reportedly used the space to the quarter-mile finish as the speed trap.

A special safety review committee, in November 1984, suggested a multi-stage program of safety improvements including, but not limited to:

1. A thorough review of the physical properties of racing facilities.

2. Upgraded requirements for race cars and safety equipment.

3. A reduction in the length of the finish-line speed traps.

4. Development and implementation of improved vehicle-arresting devices and systems.

5. Establishment of professional racer safety advisory committees to provide ongoing recommendations.

“They realized that they weren’t going to slow the cars down that much, so they never did it,” noted drag racing historian Bret Kepner said. “A few of the racers got really angry when they shut off at 1,000 feet because they thought it was the finish line because there was a big pylon out there.”

“They realized that they weren’t going to slow the cars down that much, so they never did it,” noted drag racing historian Bret Kepner said. “A few of the racers got really angry when they shut off at 1,000 feet because they thought it was the finish line because there was a big pylon out there.”

In a 2010 article with CompetitionPlus.com, Funny Car team owner Jim Head recalled a conversation with Parks on the 1984 proposal.

Head referenced a conversation with Parks during the 1996 NHRA Springnationals in Columbus, Ohio.

“National Trail Raceway was an awful short track and had its share of bad accidents over the years,” explained Head. “Wally felt we should have only run 660 feet. I told Wally that was a little radical. I tried to convince him that 1,000 feet would cover it.”

Head said he and Parks had a lengthy conversation on the topic.

“He still felt strongly about the 660, and I still believed in the 1000,” Head continued. “We were both in concert that something needed to be done. The tracks that were originally built for 200 mile per hour cars thirty years earlier were nowhere close to being safe enough for 300 mile per hour cars for the lack of shutdown.

“I was widely criticized by well-known competitors. I was criticized by some of the sanctioning body officials who ran the NHRA. They accused Wally and I of trying to undermine the sport. I promise you nobody cared more about the sport that Wally and I.”

Steve Earwood, who was then in charge of NHRA’s press and publicity, admitted he was one of those NHRA officials not in favor of shortening the distance.

“I was having dinner with one of my bosses, and I told him, ‘It’s like taking third base out of baseball.”

In a previous meeting with Parks, Earwood said that the drag racing legend confided in him that he’d wish drag racing had started at the eighth-mile.

“Just because he was pro-quarter-mile didn’t mean that he was averse to sanctioning shorter distances because they did all the time,” Kepner added. “The national events had to remain quarter-mile.”

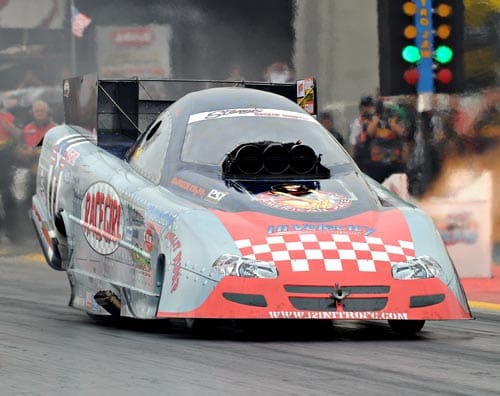

Twenty-four years later, no one could have anticipated the tragedy which cost drag racing one of its more colorful drag racing figures. Scott Kalitta was killed in an accident where his out-of-control Funny Car ran off the end of Raceway Park in Englishtown, NJ.

Because the Englishtown shutdown area was among the shortest on the NHRA tour, the conversation to run 1,000-feet began as early as the Sunday of the event.

The following week in Norwalk, Ohio, the Summit Racing Equipment NHRA Nationals was run at a quarter-mile distance. On that Sunday, June 29, 2008, the last quarter-mile NHRA nitro national event was contested.

The 2008 Mopar Mile High Nationals in Denver, Co., was the first race of the 1,000-foot era.

“It is not lost on any of us that this constitutes a change in our history of running a quarter-mile, but it’s the most immediate adjustment we can make in the interest of safety which is foremost on everyone’s mind,” Kenny Bernstein, then president of Professional Racers Organization, said in a statement after the announcement to shorten the distance. “This may be a temporary change, and we recognize it is not the total answer.”

NHRA didn’t implement the change on its own. Instead, it was demanded by the racers, and NHRA acquiesced.

In the years following the move, NHRA attempted multiple tests unsuccessfully to slow the cars down to a point where nitro cars could run to the quarter-mile. The end result is that the cars would progress to running just as fast, and any change would be akin to kicking the can down the road.

In 2005, Tony Schumacher established the speed world record at 337.58 miles per hour while racing in Brainerd, Minn. Two years ago in Las Vegas, Brittany Force posted the fastest Top Fuel speed in the 1,000-foot era with a 338.17. Two weeks ago, also in Las Vegas, she came within a whisker of topping the mark with a 338.00 blast. The fastest mark for the Funny Cars came in July 2017 when Force’s teammate Robert Hight ran 339.87 at Sonoma. NHRA implemented new header angle rules, but those proved to be a bandaid on a bullet wound at Ron Capps knocked on the door of 340 with a 339.28 trap speed in September 2019 in mineshaft conditions at Maple Grove Raceway.

The most impressive part of Force’s 338 speed two weeks ago was that it was done at 3,000-feet of density altitude.

The fastest speed in the quarter-mile now stands as 338.35, recorded by Dom Lagana in 2017. His car ran 321 to the 1,000-foot on the pass.

The most significant difference in 1984 to 2022 is that the Camping World Drag Racing Series cars ran 200 miles per hour to the eighth-mile, and today the fuelers are knocking on the door of 300 miles per hour.

“In 1989, Connie Kalitta was the first one over 290 in the quarter-mile,” Kepner said. So in 33 years, we’re doing that in the eighth. Now, granted, the rules are different, but it doesn’t matter. In fact, that’s kind of the point of our conversation. The rules are different, and they still went 299.”

“In 1989, Connie Kalitta was the first one over 290 in the quarter-mile,” Kepner said. So in 33 years, we’re doing that in the eighth. Now, granted, the rules are different, but it doesn’t matter. In fact, that’s kind of the point of our conversation. The rules are different, and they still went 299.”

Without rev-limiters, Kepner knows the sky would be the limit.

“God knows how fast we’d be going in the 1000 feet; it would certainly be every bit of 340,” Kepner said.

In Bonneville competition, a Top Fuel dragster would classify as a Lakester, and the fastest one has gone 377 miles per hour.

The fastest eighth-mile speed belongs to Shawn Langdon, who ran 299.33 miles per hour in Brainerd, Minn. A run conversion to the quarter-mile would translate to 360.74 miles per hour without a rev-limiter.

And in 1984, that would have frightened Parks and the insurance companies beyond measure.