Ted Jones had an open-door policy with IHRA founder Larry Carrier, and while he tried to not wear out his welcome, on a fall day in 1976 he couldn’t resist bringing his idea to the boss.

Jones was the VP of Competition for the five-year-old sanctioning body, and little did he know that his intuition would one day change the way the Pro Stock division would be contested. The IHRA was always searching for its niche in a drag racing world dominated by the National Hot Rod Association, and to a point the now-defunct American Hot Rod Association.

Jones wanted to do away with the status quo for the Pro Stocks. He was tired of following the NHRA’s lead of factoring cars into competitiveness, and the aggravation that came along with policing it. His idea of throwing the standard formula of pounds to cubic inch out the window had the potential to be taken one of two ways – (A) the greatest thing since sliced bread or (B) downright blasphemous. The bottom line is that Jones had to deal with the never-ending issue and not Carrier.

“It was a nightmare without end because you always had to adjust the rules,” Jones, who now owns a television production company, said. “You had several weight breaks and they were for every combination under the sun. You had them for staggered valves, cylinder heads, wheelbase, and so on and so forth.

“Most every Pro Stocker had to run a small block because if you didn’t, you’d have to run so much weight that it was unreasonable and the parts breakage for running such a heavy combination was unreal. It was a real headache.”

That headache threatened the mere existence of the IHRA’s version of the factory hot rod division. Jones said the constant factoring of one popular combination, once a staple in the class, is what inspired him to study the feasibility of another way to do Pro Stock business. The Chrysler Hemi had all been penciled out of competition.

However, it wasn’t the factoring that put the fear in his heart. It was the reality that one of the most storied teams in drag racing was about to throw in the towel that got his attention.

When Pro Stock teammates Ronnie Sox and Buddy Martin made plans to quit at the end of the 1976 season, it got Jones’ attention. He’d heard some rumors about a few backwoods match-race venues where large cubic inch engines lurked under the hoods of cars originally built with small block powerplants in minds. That idea caught his attention and he made plans to attend one of the events incognito.

“I went (to Roxboro, North Carolina) one Saturday night and watched these big 500-inch cars run. The excitement of the crowd was all I needed to see,” Jones said.

First thing on Monday morning, Jones was in Carrier’s office.

“When I went back to work I was inspired:” Jones said. “I was tired of the never-ending nightmare. I had watched Bob Glidden get the Ford Cleveland combination hammered so much that he was the only one competitive with that combination. I walked into Larry’s office and asked if he wanted to make our Pro Stock cars scream and have the class become a conversation piece. I knew he was interested in what I was saying and I couldn’t help it. The presentation began flowing.

“I told him that we needed to come out with a new version of Pro Stock and call it run whatcha brung. No cubic inch limits … bolt in the biggest damn motor you can in the car and bring it on. There will be safety of course. But make them weigh 2,350 pounds, run pump gas and have two four barrel carburetors. We don’t even need to know how big the motors are. We’ll just tell them to put the big motors in there and come on out and race.”

Carrier took in the idea, looked at Jones and simply said, “Make it happen.”

Thirty years ago, sanctioned mountain motor Pro Stock racing began with a favorable nod.

“Back then a mountain motor was 500 inches,” Jones said. “Mountain motor became the natural nickname for the engines. They were big as mountains and most were built there, too. It started catching on and the next thing you know, we were attracting the big names to run the big motors.”

It’s common knowledge that motors are powered by electricity and engines by gasoline. However, the term Mountain Engine just didn’t sound right. The southern terminology made it mountain motors.

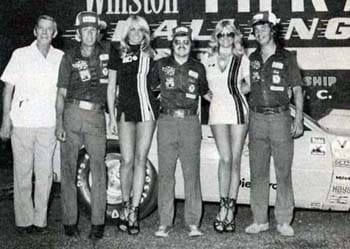

If those motors were being built in the mountains of Virginia, Tennessee, and the Carolinas, it only made sense that two of the more colorful racers from the region, Roy Hill, and “General” Lee Edwards, participated.

“We were making about 1,000 horsepower in those early days with the big motors, so it fit in well with what we were doing,” Hill said. “We had just come out with the six-lever clutch and it made those mountain motor cars really run well. Today everybody uses 6 to 9 lever clutches. The Pro Stock class is now running about 1,300 horsepower. But the gains we made early on were huge. Our clutch knowledge wasn’t that strong but I think my team had an advantage in that area. That came from years and years of traveling up and down those small race tracks.”

“I was all for the switch,” Hill said. “I had to carry all of the weight for the big Hemi. So when they said 2350 pounds across the board, I got to take weight out. I was having to run 2,700 and all of a sudden we had to find out how to make our car work.”

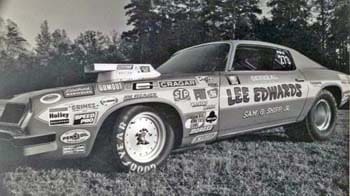

Edwards was considered one of the more prolific runners in those formative days of the movement. He earned a living Pro Stock racing under both the NHRA and IHRA banners throughout the 1970s.

“It suited me well because I already had some big motors,” Edwards said. “I just kind of fell into running the new style. Most of us had those big motors sitting around for match races and it played right into our hands.”

It fell into Edwards’ hands more than any other driver. He claimed the first two world championships in convincing fashion, winning the 1977 title by 905 points and following up the next year winning by a whopping 3,111 points.

The common denominator in both of those championship conquests was not only did he win by gargantuan proportions, but also the runner-up each year was Pat Musi.

Musi gave up Pro Stock racing a long time ago in favor of Pro Street and Pro Modified competition. But if you ask him about the days when the big inch motors replaced the pounds per cubic inchers, he’ll smile and spin yarns about what he calls the “good old days.”

The ironic part of it all is that Musi wasn’t a fan of the IHRA’s new format initially.

“I had a pretty good program with the pounds-per-cubic-inch, so I wasn’t real enthused about the switch,” Musi said. “I hadn’t run a motor that big before, so I was kind of in on the ground floor with things.”

Musi wasn’t the only small block stalwart to get roped into the newfound brand of Pro Stock racing. In those formative years, virtual unknowns such as John Brumley, Sam Carroll, Billy Ewing, and Calvin Nabors earned the opportunity to mix it up with legends such as Ronnie Sox, Don Carlton, and Dyno Don Nicholson.

Warren Johnson was on his way to legendary status and the mountain motor concept helped to catapult him to stardom. Johnson swam upstream when compared to his fellow pounds-per-inch comrades. He carried the heavyweights because he chose to run a large displacement engine.

“That was the good ol’ southern boys,” Johnson said. “They just put the big motors in there instead of working on those small blocks. That was just the good old boys being lazy.”

Despite his good-natured ribbing, Johnson did play with the good old boys and in 1981 even moved down “into their neck of the woods” to be closer to team owner Jerome Bradford. For his efforts, the Duluth, Georgia-based Johnson turned in two world championships (1979 and 1980) as well as 13 national event victories.

Bob Glidden was a regular on the IHRA tour in the early 1970s but stepped away when the mountain motor concept was first introduced. He returned in the 1980s on a regular basis when Motorcraft was a major sponsor of the IHRA. Glidden admits the IHRA Pro Stock racers were very tough racers.

“There were some great racers that raced in the mountain motor style of Pro Stock,” Glidden said. “You look at the big names that came out of there and just saying the name Rickie Smith says a lot about the caliber of racers that competed there. It was just a lot of fun racing over there.”

Steve Brock, a part-time sportsman drag racer and full-time fan from Spartanburg, SC, was in Darlington to witness the debut of the big motors at the 1977 IHRA Winter Nationals.

“You knew that something was different by the way the cars sounded when they came out of the water box,” Brock said. “Instead of that high-pitched sound, it was a deep rumble. When they let the clutch out the people sitting around me went crazy. They yelled for them like they did the nitro cars.

“I remember watching Lee Edwards that weekend. The way he handled that car made me a fan right off the bat. I’d always been a dragster guy and in those days, you were either one or the other. That day I became a doorslammer fan. I think a lot of other people alongside me did, too.”

Little did Jones and the rest of the racing world know, this version of Pro Stock would go on to create a media blitz that would inevitably topple the factorization of the class by every other sanctioning body. It would also inspire growth in the IHRA’s only bracket racing category (Top Sportsman) and lead to the eventual implementation of another doorslammer classification – Pro Modified.

The IHRA Pro Stock division has been contested continuously since 1971, longer than any other professional class. (EDITOR’S NOTE – Following the 2009 season, the IHRA under the leadership of Aaron Polburn and Skooter Peaco ceased open competition, bringing to an end the continuous streak).

FROM MOLEHILLS TO MOUNTAINS

Edwards said his initial engine was a 490-incher but that was only a stepping-stone. Within two years the average size had grown to 570-inches and was heading well into the upper 600-inch range, thanks to the implementation the Rodeck block, and later a new version from the PNS foundry. Current class engine builder Sonny Leonard was responsible for the latter.

In that first year of competition, the majority of the engines were nothing more than the standard factory casts. There were creative ways to get more cubic inches, though, and guys like Edwards found a way to get them.

The universal theme for the Mountain Motor Pro Stock division was a common weight with unlimited engine size, but there were some variations in weight depending on the block used.

“There was nothing out there to buy, we had to make it all,” Edwards said. “We used stock blocks and made the best out of what we had to work with. Things got pretty innovative. But I didn’t mess around. I just made them as big as I could make them. That was one of the keys to my success.”

Edwards said he took advantage of a rule that enabled teams to run at 2,350 if a racer used the car-height block. The option was there to run at 2,400 pounds if they used a truck-height block.

“One of my tricks is that I would take a car-height block and stuff a big crankshaft in it,” Edwards said. “I’d put a bunch of head gaskets on it and get by at 2,350 pounds. I had to have a big motor.”

Later Edwards worked his way over to a Rodeck block, which became the preferred combination by many of the leading racers of the day. The early days of the Rodecks came with a 100-pound weight penalty. But for some, nothing replaced the traditional Detroit steel.

In 1981, Jack Roush had no qualms about drawing 588 cubic inches from the traditional Boss 429 block from Ford. In fact, Ronnie Sox drove a Ford to the title in 1981 and Rickie Smith, using the same combination with former Dyno Don Nicholson crew chief Jon Kaase, won the 1982 title before Reher – Morrison – Shepherd became the kings of the hill with a mid-500 inch engine during the next two seasons.

The early part of the 1980s proved to be the formative years for one of premiere mountain motor racers. Sonny Leonard advanced into the arena after building big-inch Modified Production engines for fellow racers. He raced a bit of the mountain motor stuff too until rolling his Vega in 1978 and then determining the cost of rebuilding to be prohibitive.

“In those early days it was really hard to find the blocks, so you did whatever you could to make the engines bigger,” Leonard said. “The camshafts – you’d put more stroke into it and your rods would hit the camshafts. It was a headache.”

Leonard said that was par for the course until a company named PNS developed a block to accommodate the bigger is better theory.

“PNS came out with the block that had the camshaft moved up a quarter of an inch,” Leonard said. “What that did is allowed you to put in more stroke in it to allow your rod to clear the camshaft. This was the first one available to the public.”

This inclusion allowed the engines to grow from 550 inches to 700 inches.

“That really opened up the avenues for the aftermarket companies,” Leonard said. “It helped the industry because the company could use the big block Chevy as a baseline. You could get wider pan rails, move the cam up and make your decks taller. It opened up a lot of other avenues outside of drag racing.”

The Chrysler Hemi combination never really got into the size game like the Chevrolets and Fords. The initial engines displaced 440 inches but expanded over time to as large as 480-inches when using a 4.5-inch crank.

Hill said the Mopar camp preferred the steel blocks to the aluminum versions for durability and performance. He did admit using a Keith Black block before heading over to the Ford camp in the early 1980s.

WHAT THE HAY? DARNED WHEELS MUST’VE FELL OFF

The biggest difference in the pounds-per-cube cars and the new mountain motor cars was not the obvious one of bigger inches. The real factor was torque. There was an incredible increase in that and while the engines were producing more horsepower than a Pro Stocker ever experienced it was inadequate to work in perfect harmony with the rest of the combination. In other words, the drivers were demanding more of the tires than could possibly be delivered.

That led to something the doorslammer guys were unaccustomed to – tire-shake. And, this wasn’t your average vibration and business as usual rattling. This was essentially jarring your head, head-in-the-paint mixer and shake your fillings out level of tire shake.

It’s a common occurrence today, but back then no one knew what it was. Well, maybe a few like Warren Johnson and those who had ever tested tires, but not the majority of drivers in the mountain motor arena.

Musi claims credit for being one of the first with a mountain motor to experience it.

“No one had ever really experienced tire-shake in a Pro Stock car before at a national event,” Musi said. “I was one of the first to get it. It shook the tires hard and you just didn’t do that in a Pro Stock car. No one went fast enough to shake the tires.”

Even the seasoned veterans were puzzled.

“We had Richie Zul working with us and he suggested the driveshaft was out of balance,” Musi said. “I didn’t know what happened. I thought the wheels fell off of the car.”

Some went into that first event in Darlington knowing what to expect. You can file Hill’s name under the experienced rattlers.

“I was testing along with my buddy Butch Leal out in Irwindale before that first season,” Hill said. “We had made some big advancement with the intake manifold and we were trying to replace torque with high rpm power. That’s when I experienced it.

“I didn’t know what in the heck it was. I thought the driveshaft was coming out of the car. I had tire shake so hard once that it knocked the headlight out of the car [back then we had to run them like that] and I ran over it and cut my tire. Now that was tire shake, son.”

Hill said the best way he had to combat that tire shake was to put screws to the tire.

“This experience goes back to the middle 1960s when we ran a 12-inch tire on a 10-inch wheel,” Hill said. “I remember working with Sam Kennedy and he had a 6 and 7 inch wheel with a 12-inch tire. He had screws off of each stud. He ran 6 or 7 pounds of air in the tire. The wide wheel would be around 15 pounds.

“As the tire wadded up and went out, it would spring up and go down the track. All of a sudden we had so much power, the screws would bring the tire into a big wad and then tire shake would follow. We learned by accident at Darlington. The standard procedure when you got a new car is that you got a new set of wheels with it. I had a new Plymouth Arrow and had set it up to run the same kind of wheels my old Duster had.

“I was shaking my butt off with my new car. I put on my old tires and wheels from the Duster and it went just as smooth as you could get. I made a dumb decision before the final round and went back to my new and shiny wheels before the finals so the car would look good in the finals – and I went out and shook my brains out.

“I got a picture of the final round and sure enough, it had those shiny wheels with tire all wadded up. My other pictures showed the other wheels and the wad was less. The difference is that I had more screws [10] in those tires. By the mid-Eighties, I was running about 20 and later on the bead-locks came in.”

Hill wasn’t the only driver who had advance warning. Johnson pointed out that he ran some of the smaller displacement big blocks in competition. Likewise, he tested tires for the scenario.

“I really experienced tire shake when I started doing the tire tests for Firestone and they experimented with tire construction and compounds,” Johnson said. “That was my experience with the tire shake. I had a little concept of what to expect when that came along. The tires were the weak link in the scenario.”

Edwards got his first lesson by working with the late Don Carlton. At the time, Edwards’ car was experiencing handling problems and Carlton offered his assistance. Yes, the car went straight but Edwards learned how to basketball a tire.

“Don had worked with Chrysler on some of the first four-link cars,” Edwards said. “We were in Atlanta and my car just kept going crooked, so Don asked me where I was going when I left the track. When I told him I was headed home, he told me to come by his shop.

“He put a four-link under that car and it was the damndest thing I’d ever saw,” Edwards said. “I went to a match race in Roxboro and it used to be that you could leave the line at 5,500 rpm and spin the tires. The first time out I pulled 5,500 and choked the tires up. After that I would just turn the thing wide open and it would haul ass.

“Shortly after that, I went to Bristol and that’s when I had my first tire shake. I didn’t know what it was but it scared the hell out of me. The thing shook the hell out of the car. The door came open and the windows fell out. It was a mess.”

Johnson pointed out that tire-shake was the big factor in determining who won many of the races in those pioneering days. That was the strongest weapon in Rickie Smith’s arsenal when he joined the tour in late 1978.

Leonard was convinced that made Rickie the most dangerous driver in the class. Forget WJ, Ronnie Sox, or Lee Edwards. Smith used pure driving ability to grab his share of those races and other major accolades. At least that’s how Leonard sees it.

“The cars would shake third gear and Rickie had a system of back-pedaling and shifting the car and it would go right through the shake like nothing had ever happened,” Leonard said. “He could go a lot of places because he knew just when to pull the gear. He was synchronized at doing it.

“He’d pull the gear and back down on the throttle and go back at it and the shake would disappear. He was the best I had ever seen.”

FATE PUTS A NAME IN THE HISTORY BOOKS

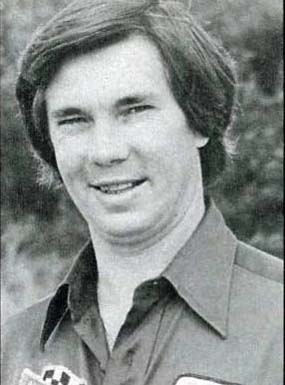

Harold Denton has long since retired from Pro Stock racing but always had a penchant for being at the right place at the right time. That’s exactly what provided him with the opportunity to become the first driver to ever win an IHRA mountain motor Pro Stock national event title. It just happened to be the first time that Denton had ever won in his life.

“I don’t think any one of us envisioned ourselves as making history that day,” Denton said. “It was just something new that was coming along and I felt our car was competitive enough, so we gave it a shot. If you had asked me what my odds were that day, I would have said 8-to-1.

“I saw the guys racing there like Ronnie Sox and Roy Hill and I knew they had much more money than I had to work with. I was on my own dime. Being smart enough to race was one thing, but having the money to do it with was another.

“I always think of that day when reminded one time some advice that Kenny Bernstein gave me. He said, ‘Money won’t make you a winner but you can’t win without money.”

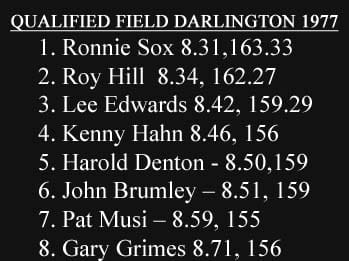

Denton used an old IHRA break rule to put himself into that position. The scene was Darlington, SC., on a Sunday afternoon in March of 1977.

Denton had the misfortune of crossing paths with low qualifier Ronnie Sox (8.31) in the semifinals of the eight-car show. As expected, Sox sent Denton packing, but what wasn’t expected was the engine damage to the trusty Hemi, which made returning for the final round prohibitive.

Denton was reinstated for the final round but that wouldn’t prove any easier as Hill was the No. 2 qualifier (8.34). Hill seemed a lock for the win but tire shake forced him to abort [scroll back to WHAT THE HAY?] for Hill’s account) of the run.

That wouldn’t be the only time Denton would make history. Fourteen years later, he would become the first driver to ever record a six-second lap in a Pro Stocker and it just so happened that he did it in Darlington.

Denton will be the first to admit that he never expected the format to catch on.

“I really didn’t,” Denton said. “It just seemed like a backyard kind of thing, like sandlot baseball. I never believed it would turn into what it is. It was a time for the country boys to shine.”

Little did those competitors know that a driver would be watching from the sportsman pits who would come along at the right place and right time to be forever immortalized.

Coincidently, Rickie Smith won the Super Modified division that day and began a clean-sweep season that would inevitably cancel the class and graduate him and team owner Keith Fowler into the mountain motor Pro Stock ranks.