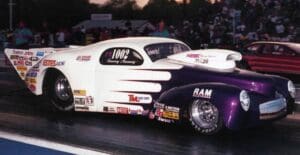

Annette Summer knew she’d have a lot of eyes on her when she rolled to the starting line in November 2025 at the IHRA season finale at Darana Motorsports Park in Dunn, North Carolina. She also understood that many of those eyes were focused less on the driver than on the purple-scalloped 1941 Willys, known across Pro Modified history simply as Barney.

Summer, an iconic Pro Street figure from the formative years of heads-up doorslammer racing, recognized the moment carried weight beyond elapsed time. She wasn’t just making a pass, she was reintroducing a car that once defined consistency and reliability in nitrous Pro Modified competition.

Barney’s reputation was forged in the mid-1990s, when repeatability mattered as much as peak speed. In a five-season stretch, the car won 13 national events and reached 20 final rounds, establishing itself as one of the most successful nitrous Pro Modified entries of its era.

The car Summer debuted is the same championship-winning platform that captured the 1995 IHRA Pro Modified title and continued collecting trophies as it changed hands. Barney has had only four owners in its existence: builder Tommy Mauney, the Parsons Brothers (Kevin, Doug, and Mark), Milton Ledford, and now Summer.

Summer entered the car into IHRA Pro Modified without the expectation of running near the top of today’s qualifying order. Instead, the appearance served as a visual and mechanical reference point, reminding longtime fans just how far the class has evolved.

What Summer placed on the racetrack in 2025 was not a reimagined tribute or a modernized homage. It was a preserved predator, a car that looked playful only in nickname, because from the moment it appeared on the IHRA tour, it raced with the demeanor of something hunting.

Tommy Mauney finished the car in 1994, and he said there was never an expectation it would become a historical marker. “No,” Mauney said. “I just done the Willys because of the other thing. I just liked them. It didn’t start out nothing no more than just another car.”

The early life of Barney was shaped by workload rather than legacy. Pro Modified racing in the mid-1990s rewarded teams willing to race frequently, and Mauney said they chased events wherever opportunities appeared.

“Back then everybody run good, and if you could just run with all them guys and stuff you were doing good,” Mauney said. “There were a lot of weekends that we’d race two and three times a weekend. Same thing Scotty was doing.”

Even Barney’s iconic look took time to settle into form. “It started out white,” Mauney said, recalling how criticism of the original appearance sent the car back for the purple scallops that later became inseparable from its identity.

The chassis reflected lessons learned from parallel programs rather than a singular design leap. “This was definitely the chassis basically right out of the… just like the funny car deal, but with the Willys body on it,” Mauney said.

The body itself was never an aerodynamic advantage, and Mauney acknowledged the compromises. “Aerodynamically, it wasn’t helping anything,” he said, noting the car required constant trimming and adjustment to regain speed.

While the Willys body added drag, the underlying layout gave crews something rare in that era: accessibility. Mauney said Barney became easier to service than many competitors, a factor that mattered in a class defined by relentless maintenance.

“Well, all the cars in had clutches in them,” Mauney said. “You could be on your knees outside the car and do anything you wanted to do on the clutch.”

That access enabled experimentation, as teams routinely swapped transmissions, rear gears, tires, and clutch setups to suit quarter-mile and eighth-mile configurations. Barney absorbed those changes without becoming unpredictable.

“We were doing a lot of stuff trying stuff,” Mauney said. “But the car was so forgiving.”

With hindsight, Mauney sees areas where Barney could have been even better. “If I’d have known then what I know now,” he said, “we was giving up a couple hundreds at 60 foot in the finish line because of the front end on the car.”

That reflection underscores why Barney’s results still resonate decades later. The car achieved its record without fully exhausting its potential, making Summer’s 2025 appearance feel less like revival and more like continuation.

Mauney said Barney’s dominance came from accumulation rather than a single breakthrough. Small gains in nitrous tuning, engine development, and chassis balance stacked together over time.

“Well, you can always lose,” Mauney said. “All that stuff really worked good, but you were still learning.”

Pro Modified schedules of the era blurred national and regional boundaries, and Mauney said they filled open weekends with match races and Quick 8 programs. The repetition built both speed and familiarity, and Barney thrived in that environment.

When asked if he regrets selling the car, Mauney was direct. “Well, if I could have kept any of them, that would have been the one I should have kept or would have kept.”

He admitted attachment wasn’t his usual way. “I liked that car probably better than any car that I’ve raced,” Mauney said. “It was just cool. It was good for T-shirt sales.”

That identity mattered as the class became crowded with similar shapes. Mauney said later seasons filled pit areas with Corvettes that blended together, while Barney never disappeared into the background.

For competitors, Barney became a standard rather than a curiosity. Scotty Cannon, long considered the benchmark for supercharged Pro Modified, said the car earned its reputation regardless of power adder.

“Absolutely,” Cannon said. “When they have a car that goes up and down the racetrack, I always call them like a unicorn. That was one of them.”

Cannon said the challenge was magnified by the people behind the program. “Tommy Mauney wasn’t no slouch,” he said. “When they got all that stuff together, it was a nightmare.”

He framed the competitive bar in unmistakable terms. “That’s one thing that’s hard to do about Tommy Mauney is beat him,” Cannon said. “You got to beat him a lot to even think about being any good against him.”

Cannon also credited the era for accelerating development across the class. With teams racing on different tracks nearly every weekend, data accumulated quickly and lessons spread.

“You got a lot of data,” Cannon said, describing how information flowed between programs in a time before modern analytics.

The Willys cars Mauney built shared close DNA, Cannon said. “Oh, sisters,” he said, explaining that Barney and his own 1995 Willys differed only slightly in component placement.

Cannon described the 1990s as “a Tommy Mauney landslide” for competitive cars, a stretch where Mauney-built machines consistently defined the pace. Barney wasn’t isolated excellence, but part of a broader pattern.

That context shaped Cannon’s reaction when Summer returned the car to the track. Rivalry faded quickly, replaced by appreciation.

“We were stoked, man,” Cannon said. “S***. One thing’s for sure, if there was anybody that didn’t like her, they didn’t say anything because then she sure got a standing location.”

Cannon said Summer’s place in the sport mattered as much as the car itself. “She’s just a trooper,” he said, calling her “the first lady of drag racing as far as Pro Mod comes.”

Shannon Jenkins experienced Barney from the inside, first as crew chief and later as the driver who extracted its most prolific results. He traced the car’s path before its championship reputation took hold.

“Barney was built in ’94,” Jenkins said, noting it ran shootouts and Quick 8 races before becoming a full-time IHRA contender.

In 1995, Jenkins served as crew chief while Mauney drove the car to the IHRA Pro Modified championship. At season’s end, the Parsons Brothers purchased the car and placed Jenkins behind the wheel.

From 1996 through early 2000, the results piled up. Jenkins drove Barney to five final rounds in 1996, winning three, then went four-for-four in finals during his 1997 championship season.

He added two wins in 1998, both over Cannon, and in winning his second IHRA world championship in 1999, Jenkins captured two of four final rounds. Barney didn’t just win, it lived in the final round.

Jenkins said the car’s defining trait was balance. “It was a perfect car balance for the power and the cubic engines that we had back in those days,” he said.

That balance allowed aggressive tuning without instability. “That’s exactly what it did,” Jenkins said when asked if the car could take whatever was thrown at it.

Jenkins said seeing Barney return reignited something dormant. “Oh, I was really happy,” he said, noting conversations with Summer and her husband, Vernon Summer, during the car’s reassembly.

He viewed the 4.20-second passes not as a ceiling but as a starting point. “Sometimes you can think it went a 20,” Jenkins said. “That’s two-tenths from a four flat and that’s a lot.”

When asked if Barney might have been the best car Mauney ever built, Jenkins didn’t hesitate. He said. “No doubt about it.”

For Summer, the story began long before ownership. “Well, it was always my favorite,” she said, recalling first seeing Barney while her Pro Street car was being worked on at Mauney’s shop.

“But it was a love you couldn’t have,” she said.

The opportunity surfaced years later while discussing work needed to revive her pink Pro Street car, Old Pink. Standing in Mauney’s office, Summer noticed a photograph on the wall.

“I said, ‘There’s Old Barney hanging on the wall,’” Summer recalled. “I said, ‘That’s my favorite car ever.’”

Mauney encouraged her to pursue it, writing down Milton Ledford’s phone number. Ledford, Summer said, refused buyers who wanted to alter the car’s identity.

“They would call and say they’re going to do all this crazy stuff to the car and put blower motors in it and all this crap,” she said.

Summer said the purchase nearly stalled as Ledford’s health slowed the process of gathering parts. Original magnesium pieces and components were spread across multiple garages and storage areas.

While Ledford collected everything, interest from other buyers grew, including inquiries from overseas. Ledford refused to let the car leave the United States.

“He said, ‘That car’s staying here,’” Summer recalled.

Summer said the deal was made possible by a longtime family friend who stepped in when timing and finances didn’t align. She had moved to North Carolina, her Aiken home had not sold, and the opportunity arrived before the equity.

“He said, ‘When your house sells, you’ll pay me back,’” Summer said, adding there was no paperwork and no deadline. “I never thought somebody would loan me that kind of money without any paperwork or anything.”

She said she offered to take out a formal loan but was told not to worry. “Everybody thinks I’m rich, but I’m not rich,” Summer said. “I think when you help other people, it comes back to you.”

Once acquired, Summer made her intentions clear. Asked if she planned to modernize the car, her answer was brief. “Zero,” she said.

“I want to keep that car intact as possible,” Summer said, describing efforts to recreate original details rather than replace them with lighter or newer components.

She said speed was never the objective. The goal was presence, memory, and continuity.

While Ledford collected everything, interest from other buyers grew, including inquiries from overseas. Ledford refused to let the car leave the United States.

“He said, ‘That car’s staying here,’” Summer recalled.

Summer said the deal was made possible by a longtime family friend who stepped in when timing and finances didn’t align. She had moved to North Carolina, her Aiken home had not sold, and the opportunity arrived before the equity.

“He said, ‘When your house sells, you’ll pay me back,’” Summer said, adding there was no paperwork and no deadline. “I never thought somebody would loan me that kind of money without any paperwork or anything.”

She said she offered to take out a formal loan but was told not to worry. “Everybody thinks I’m rich, but I’m not rich,” Summer said. “I think when you help other people, it comes back to you.”

Once acquired, Summer made her intentions clear. Asked if she planned to modernize the car, her answer was brief. “Zero,” she said.

“I want to keep that car intact as possible,” Summer said, describing efforts to recreate original details rather than replace them with lighter or newer components.

She said speed was never the objective. The goal was presence, memory, and continuity.

Summer said she plans to continue running Barney and possibly use it in match-race settings. Part of that vision includes assembling other period-correct Pro Modified cars to recreate the atmosphere that defined the class in the 1990s.

She said longtime racer Cory Evenson, known for the Witchdoctor and CT Chevelle programs, is among those she has spoken with as she works to gather familiar names and machines that help place Barney back into proper context.

Summer listed the names she calls heroes, and she made clear it goes beyond rivalry or brand. “These are heroes that helped me get to where I was, was Gene Fulton, Tommy Mauney, Shannon Jenkins, and Ron Santhuff,” Summer said.

As the car returned to the track, its meaning became clear beyond numbers or nostalgia.

“Cars like this aren’t supposed to disappear,” Summer said. “They’re supposed to remind people where this class came from.”