Geoff Turk admitted he once had a fleeting interest in movie-making. But even the guy whose then-future stepdaughter Erin once said, “You’re either a pathological liar, or you’ve had a hell of a life,” couldn’t have generated a script that produced the drama that played out in his life over the last few months.

Geoff Turk admitted he once had a fleeting interest in movie-making. But even the guy whose then-future stepdaughter Erin once said, “You’re either a pathological liar, or you’ve had a hell of a life,” couldn’t have generated a script that produced the drama that played out in his life over the last few months.

When the Factory Stock Showdown frontrunner turned Factory X pioneer suddenly forgot how to send a text on his cell phone, he knew something was terribly wrong.

“I’d go to text and I asked my wife [Jena], ‘Hey, do you text with your thumb? Did they change the Apple keyboard?” Turk inquired frantically. “Because I can’t text, “I’m writing texts. I look at it; I got gibberish. And I’m trying to fix it and I got gibberish. Something’s wrong with the keyboard on the phone.”

The level-headed Turk suddenly found himself a resident in a land of confusion. The one aspect Turk had ignored, whether on purpose, in following the misguided drag racer edict of invincibility, was crystal clear. His body had been sending signals, and they would not remain unanswered.

Numbness in one arm and massive headaches were a signal that all was not fine following his 190-mph accident eight weeks earlier while testing his new Blackbird Dodge Challenger. The incident was severe to the point Turk was diagnosed onsite with a concussion, but instead of sending him to a local hospital, he was sent home.

Caring about his physical body ranked low on the totem pole of importance. The day after the accident, he was in the shop assisting Dave Zientara, who had already disassembled the lion’s share of the car.

Something was wrong in the weeks following the incident, but it didn’t deter Turk from returning to the track. He tried to explain away the symptoms as possibly a viral infection that produced similar results.

Eventually, it became clear one day as he was at engine builder Tony Bischoff’s shop making dyno pulls. This situation was more than confusion over how to send a text message.

“Well, I figured I had this virus, and I kept stretching it out, saying, ‘It’s going to be okay,” Turk said. “I went over to Bischoff’s and as I went to leave Bischoff’s, I shook Tony’s hand after we did some successful work together on another engine. My hand was numb and weird, and I told him about it. I said, ‘I had some weird viral thing or something.”

RELATED STORY: FACTORY X RACER GEOFF TURK RELUCTANTLY GETS HIS PLACE IN DRAG RACING HISTORY

Turk then drove to Indianapolis to take delivery of replacement wheels, and once he went to sign his name on the paperwork, he could no longer kick the can down the road.

Turk then drove to Indianapolis to take delivery of replacement wheels, and once he went to sign his name on the paperwork, he could no longer kick the can down the road.

“I went to sign my name and I couldn’t sign it,” Turk admitted. “I couldn’t figure out how to sign my name. It wasn’t because I couldn’t move my hand, although it was a little numb and tingling. My head was throbbing. It was because I couldn’t figure it out. I couldn’t remember how to make the letters. And so that scared me. So I left there with the wheels, and I called home to Jena. I said, ‘Hey, this has happening.”

Jena immediately asked why he was driving and counseled him to call his doctor or drive to the nearest hospital. When the doctor’s office didn’t call back, Turk completed his drive home. Shortly after that, he visited the emergency room, figuring it would be at least two hours of his life he’d never get back.

Instead, it was two hours that saved his life.

“They took me straight back after they heard my symptoms,” Turk said. “They did a CT scan in five minutes, and five minutes later, they said, ‘We got a helicopter inbound from Nashville. You’re getting on the helicopter. You’re going to this neurosurgeon trauma place in Nashville so they can take care of you.”

Turk then asked the doctor why they couldn’t do anything for him. He learned the age-old adage, “Don’t ask the question if you aren’t prepared for the answer.”

“He looked at me and said, “Our job right now is to keep you alive till you get to Nashville.”

The symptoms Turk had been playing off as a virus were two major brain bleeds. He was in the middle of an acute brain bleed when he visited the hospital. The hospital was having difficulty controlling his blood pressure at the time.

“The doctor was as serious as one can be when he said, ‘We got to get your blood pressure down because it’s making it worse. And we got to get you on this helicopter and get you there so the neurosurgeons can decide what to do,” Turk recalled.

The options available sounded anything but comforting. The surgeons could drill holes in his skull or take out a chunk of his skull altogether to alleviate pressure from the bleeding and repair damaged arteries.

Turk was doing fine on the flight until the last 15 minutes when his blood pressure skyrocketed. The medical team got him stabilized and rushed him into the Nashville hospital’s Neuro ICU unit shortly after landing.

Turk was doing fine on the flight until the last 15 minutes when his blood pressure skyrocketed. The medical team got him stabilized and rushed him into the Nashville hospital’s Neuro ICU unit shortly after landing.

Turk remained hospitalized for 24 hours, and doctors would come into his room every hour on the hour to test his cognitive skills. In a situation like Turk’s, the patient’s situation usually deteriorates. Remarkably, it was the first time he’d stayed overnight as a patient.

Turk was aware of the visitors in and out, and it was not all medical personnel. The severity of the situation he faced at the moment became apparent.

“And it turns out, if you’re my age, that leathery bag surrounding your brain gets more and more leathery as you age,” Turk explained. “The arteries feeding your brain aren’t really supposed to put much blood up around this area, around the outside of the leather. When you’ve ripped open the arteries around this by banging your head into a wall at 20 Gs or whatever, and they’ve got torn up, and they’re putting blood in there, and it can’t get out.”

The harsh reality, Turk learned, is that nine out of ten people his age (59) die from this type of injury, and those who do survive suffer some permanent paralysis.

Once doctors stabilized Turk, he was taken into a less invasive surgery where doctors repaired the leaking arteries. The moments before the surgery were probably some of the tensest and the most real life-experience moments.

“As I went into surgery, they were trying to knock me out under general anesthesia,” Turk recalled. “I’ve never been under general anesthesia. My life’s been pretty blessed. I’ve been hurt a lot, but I’ve never had to get knocked clean out. And this was deep general anesthesia, and they had to put a tube down your throat to keep you breathing, and they had to closely monitor everything because you could die, obviously. And they kept trying to knock me out for the doctor out there.

“I said, ‘No, I want to talk to the guy and shake the guy’s hands whose life I’m going to put in his hands.”

“I remember praying and saying to God, “I’ve had a great life. I got nothing to complain about. I’ve had a fantastic life. I said, ‘God, there’s three people up in my hospital room, and there’s many other people that are going be pretty torn up if you take me out of here. So if you can, could you leave me here a little longer for them? On the other hand, if you got to take me, you got to take me. And they got to get through it. I understand. I’ve been through this. I can’t complain about my life. You’ve been great to me. I’m so thankful and blessed to have the life I have.”

Then Turk woke up hours later in the recovery room. The surgery was a success.

Then Turk woke up hours later in the recovery room. The surgery was a success.

“They sent me home a couple of days later after they saw that I was getting better,” Turk said. “The last thing I was worried about was not driving a race car. I was just happy to be alive and happy not to be disabled. I could still walk and talk. And turns out the next day or two, the blood was still up there because they don’t drain the blood out this way; they just shut the blood off. It was moving around.”

The recovery had its moments, such as numbness moments in his arm and his face. “I’m a guy that’s always doing things, always thinking, always talking, and just to be able to stare at a wall for two hours and be happy staring at a wall, it was so bizarre,” Turk explained. “And then, luckily, just one night, I was flipping around on Apple TV, and there was a movie called Causeway, of Jennifer Lawrence returning from Afghanistan, who had a brain bleed. It shows her journey, how she just was like a zombie.

“Then she started to try to do work and do physical activity for two hours; she’s worn out. Then she tries to get the doctors to take her off the medicine because she thinks the medicine’s side effects are what’s causing all the problems. The doctor said, ‘It ain’t the side effects of the medicine, it’s your brain’s still healing.”

“I went through that for about a week and a half, and then I started researching how serious it all was and what it meant for me.”

This appreciation for life made Turk’s next major decision simple. His days of driving a race car were over.

“If I ever experience high G loading again, or if I were to bump the wall and even just have a light impact, and it created five Gs, I could have an unstoppable brain bleed,” Turk said. “So if I made a hard pass where there was a hard impact, and I felt four or five Gs, it might rattle my brain hard enough, it rips these arteries again, that they’re going to bleed faster the second time. You go from feeling this experience of having these weird side effects to most people are dead in 24 hours.”

Turk needed to look no further than the incident which claimed the life of NASCAR racer Neil Bonnett in 1994. Bonnett was involved in a 14-car crash during the TransSouth 500 at Darlington, SC. According to a report in the LA Times, Bonnett’s wife, Susan, said her husband suffered a concussion and, at the time, suffered amnesia.

Per the same report, she said that a doctor in Florence, S.C., sent Bonnett home because there is no treatment for amnesia, and he felt that Bonnett’s memory might return more quickly in familiar surroundings.

Bonnett gained medical clearance to return to racing in 1994, and in his first race back crashed into the wall and died.

“After seeing what happened to Neil Bonnett, you start coming to terms with, “Okay, I can go drive a six, seven-second car, but it’s clear you definitely shouldn’t do it for six months,” Turk said. “And even after six months, even if the scans say it’s clear, you’re taking a significant risk getting back in a car like that.

“Ultimately, I came to a decision ‘I got to move forward, and the only way for me to move forward is to accept what God’s put in front of me and make the best of it. And if God’s taken this away, maybe there’s something on the other side that’s even better. So I need to go find a driver.”

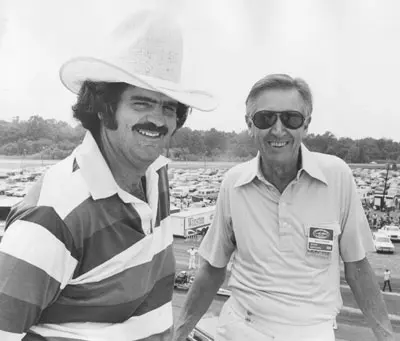

Because of Turk’s involvement with the Dodge Drag Pak Factory Stock Showdown program, he became acquainted with Allen and Roy Johnson, the last Mopar-backed team in NHRA Pro Stock.

“Ultimately I went through this whole list of people,” Turk explained. “I had several people interested, all of which are great people. And then I think, ‘Allen Johnson. I helped Alan and Roy when they first brought their drag pack out. I enjoyed working with them. They’re a father-son team; they’re great people. Obviously, they’re Mopar people to the core. And the last guy that was a player in Pro Stock in a Dodge that really did well.”

“Ultimately I went through this whole list of people,” Turk explained. “I had several people interested, all of which are great people. And then I think, ‘Allen Johnson. I helped Alan and Roy when they first brought their drag pack out. I enjoyed working with them. They’re a father-son team; they’re great people. Obviously, they’re Mopar people to the core. And the last guy that was a player in Pro Stock in a Dodge that really did well.”

Turk and the Johnsons had flirted with the idea of a Factory X car before, but it never came to fruition. This time the selling point was Turk managing the full-time and requiring Johnson only to show up and drive.

“On the 4th of July, I called Allen back and asked, ‘Would you want to do this? We made the deal. So turns the nightmare into a dream and took these lemons and made some of the best lemonade I could have ever imagined. I’ve had a ton of respect for Allen and his dad

“Now you got the blend of the two guys who, in Mopar, made those two things work, working together again. It’s a hard story to beat in terms of how it’s all played out. And despite the fact that I don’t get to drive, I get to do 90% of what I like to do and I know contributes to the outcome with people who I really like, and respect, and care about. So like so many other things in my life, this thing that was a pretty ugly thing, that was pretty hard for me to get my head around.

“It’s just my new reality and that’s the way it goes. I love helping people win and helping people period. But one of the things I’ve worked real hard throughout 43 years is learn how to make race cars go fast, and I’ll help people drive them well, and how to help people win races.”

And Turk knows how to win races, but nothing will ever compare to the biggest race he ever won – the race of life.