I’ve been writing about racing since the spring of 1977, when I was a college student and part-timer in the Sports department of The Fayetteville (NC) Observer.

I’ve been writing about racing since the spring of 1977, when I was a college student and part-timer in the Sports department of The Fayetteville (NC) Observer.

I’d been working at the paper for more than three years at that point when the man who hired me, Sports Editor Howard Ward, gave me a simple assignment: “Go out to the race track tomorrow night and bring back a story.”

I didn’t know a thing about racing then – nothing but names like Petty, Foyt and Andretti – but a great first interview with a future NASCAR champion, Sam Ard, left me with a good impression of the sport and its participants. More racing assignments came, and those led to a career writing about the people who risk it all to feed their passion.

I spent 41 full-time years at the Observer covering racing and all sorts of other sports – “everything from Special Olympics to kickboxing,” I’ve often said. I’ve enjoyed an amazing career, with lots of winning contest entries, the chance to help pick the top drivers in the first 50 years of both NASCAR and NHRA, and an award for “lifetime contributions to motorsports journalism.”

There’s no way to know how many thousands of times my byline has appeared on a story. I remember a great many people I’ve profiled or whose exploits I’ve chronicled, but I don’t remember specifics about most of the races I’ve covered. Seeing Dale Earnhardt die from the Daytona International Speedway pressbox is an obvious one that I can’t forget. Watching Tony Stewart and Carl Edwards tie for the NASCAR Cup Series championship at Homestead, Fla., was another, with Stewart taking the title on a tiebreaker.

But nothing sticks with me like a devastating crash I witnessed June 4, 1978, about two weeks after I’d been hired full-time at the Observer. Nothing could have prepared me for what happened, or that I captured it in a couple of frames on black-and-white film, or that the pictures and memories still give me chills 46-plus years later.

You may have seen the images before. They’ve been posted on the internet and Facebook for years; sometimes with credit to me as the photographer, sometimes not.

But I’ve never shared the full story behind it to a broad audience. I invite you to relive it with me.

* * * * * *

I’d never seen a drag race – ever – until the boss assigned me to cover one at the local track in the summer of ’77. Same deal as before: “Bring back a story.”

When I arrived at Cumberland International Dragstrip, which shared the same property as the asphalt track where I’d met Sam Ard, it was obvious what that story would be. Roberta Schultz was a 19-year-old alcohol funny car driver who drove a car owned by her parents, Tex and Barbara. They hauled the car to tracks on the East Coast in the back of a school bus converted into a tow vehicle.

They were so friendly and understanding of my situation as a novice racing writer, it was hard not to like them. Like Sam Ard, they gave their brand of a sport a good name, and I followed their ensuing outings as much as possible in publications such as Drag News and National Dragster.

Roberta was back in eastern North Carolina again the following June, just 90 minutes from Fayetteville at Kinston Drag Strip, set to square off against another Virginian, Carol “Bunny” Burkett. I was, and will always be, a fan of alky funny cars because that’s what hooked me on drag racing. So I hit the road that Sunday with my camera to see the match race.

When I arrived, I was surprised to discover that a nitro-burning funny car was going to be part of the show. Western Bunns had come from Danbury, Conn., with his Chevy-powered “Soul Twister” Vega to make some solo runs. The first of those would end his career.

I was admittedly a newcomer to a 35mm camera, but I knew there would be the opportunity to gain some experience shooting drag racing while I was in Kinston. Being at the top end of the track for the first time, I thought, “You haven’t shot cars with their parachutes out yet – here’s your chance.”

I did the only thing I knew to do at that early stage as a “shooter,” which was to put the lens on “infinity” — meaning, I didn’t have to focus — and point it at the finish line.

Bunns and his team pushed his car out into the waterbox, fired it up and lowered the body. Almost as soon as he crossed the starting line on his burnout, the car swerved from the left lane across the track and rolled to a stop in the grass on the other side.

He shut the car off, and a group of people pushed it back up onto the asphalt and to the waterbox. While they waited for the engine to cool for a few minutes, the crew added more fuel to give Bunns enough for another burnout and quarter-mile blast.

This time, the burnout went routinely, and Bunns backed up, pre-staged the car and crept to the line for his run.

When he dropped the hammer, the name on the side of the car — “Soul Twister” — took on a grotesque, grisly meaning.

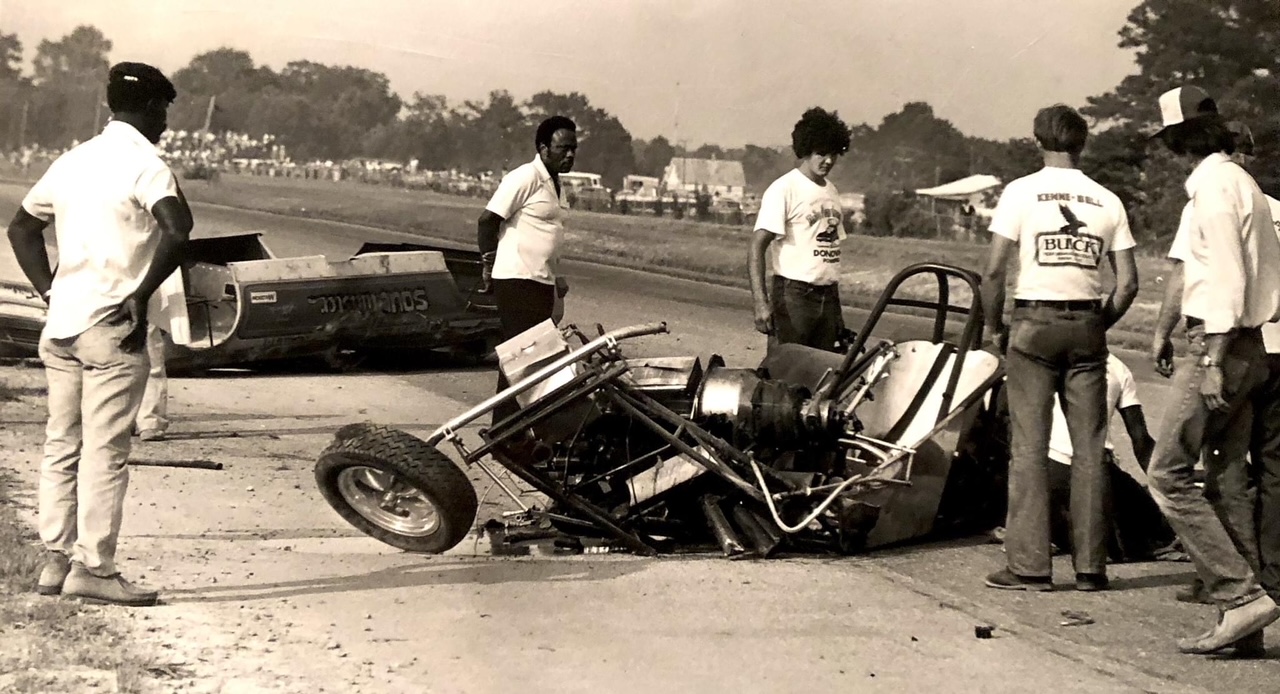

Once again, the car veered to the right and crossed the track. But this time, he was hard on the throttle, and when the nose of the car smashed into the embankment, the body was ripped from the frame, and the car began tumbling, over and over and over. The huge explosion of dirt from the impact became the backdrop to a tragedy.

I pressed the shutter button on the camera once, advanced the film, and hit the button again as the car and driver skidded to a halt near the finish line. Bunns’ body was hanging out of the car, his legs obviously broken, and people raced to the scene. I snapped one more shot of what was left of the car as onlookers surrounded its unconscious driver.

I caught Steve Aldridge as he was literally on his way out the door. Steve was a veteran of the photo staff who took great pride in being a shadetree mechanic, constantly trying to find ways to make his blue Toyota Corolla SR5 go faster. He had a need for speed, and I knew that of all the photographers on-staff, he was going to best understand my plea: “Steve! I just shot a funny car crash down at Kinston! Could ya PLEASE run the film for me and see if I got anything?”

Aldridge, being a most-laid-back dude, said yes. It wasn’t too long before the roll of film was pulled from the chemicals, rinsed in water to stop the development process, and dried. I’m sure my heart was pounding as he flipped the switch to illuminate the light table so we could see whether I’d captured anything of the crash.

He placed a loupe – a small magnifying glass – atop the film strip and let out a “WHOA!” He handed the loup to me, and when I looked through it, there on the film were two frames of Western Bunns crashing — and he was hanging out of the car in both of them.

Frame 1, when the shot is enlarged, shows his silver boots clearly above the roll cage. The body of the “Soul Twister,” detached from the frame, spins on its side.

Frame 2 speaks to the horror of the moment in greater detail. Bunns, upside down, is almost completely out of the car, head and shoulders in the floorpan, the engine flipped over in the frame, the parachutes limp and useless.

Steve quickly made prints for me, and the following morning, when the staff arrived to put out the Monday afternoon edition, I was waiting to show Howard, my boss, the pictures. He liked them so much, he ran them stacked one atop the other, in sequence, for nearly the depth of page B2. I felt so very sorry that Western Bunns had been so badly hurt and was hospitalized; I wished it hadn’t happened. But at the same time, I had no reticence about the decision to publish the pics. News is news, for better or for worse.

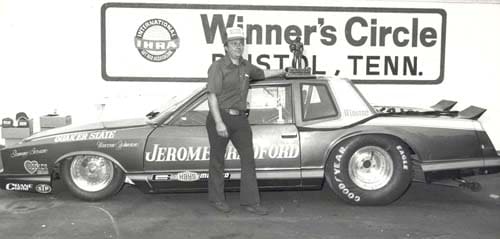

Bunns, to my knowledge, never raced again. Roberta and Bunny maintained a busy schedule of match races, entertaining tens of thousands of fans up and down the Eastern Seaboard. Burkett went on to win the 1986 IHRA Alcohol Funny Car world championship. Schultz retired a few years after Bunns’ crash, married then-Maryland International Raceway owner Tod Mack, and became a professional poker player.

The pictures captured what happened on that awful, but most memorable day, June 4, 1978. As Paul Harvey so eloquently stated at the end of each weekday radio broadcast, “And now you know … the rest of the story.”