On again, off again… and back on again. That may be what appears to be happening during a run in any of the super category classes. “Daddy, why did that car look like it broke and then came back to life?” A question for the ages.

As current super category racer Bill Phillips once said, “The first time I saw these cars running, I thought this was the stupidest thing I’d ever seen. And now I’m doing it. But it is both exciting and difficult to do at the same time.”

But how did we get to where we are today?

The concept of any of the super category classes; in fact, any of the core sportsman classes; is really very simple. Unlike brackets or the Super Stock/Stock classes, in the super categories, there is a set index and much like any breakout classes, should you run under that said index, you lose, except… Should your opponent run further under the index, the one who is the “least offender” wins.

When it comes to the super class, the problem becomes a little muddy in today’s world in the manner racers tend to accomplish the task of running dead-on their index. The common practice is to build a car which is more than capable of running under the index and use certain electronic gadgetry to slow the car down.

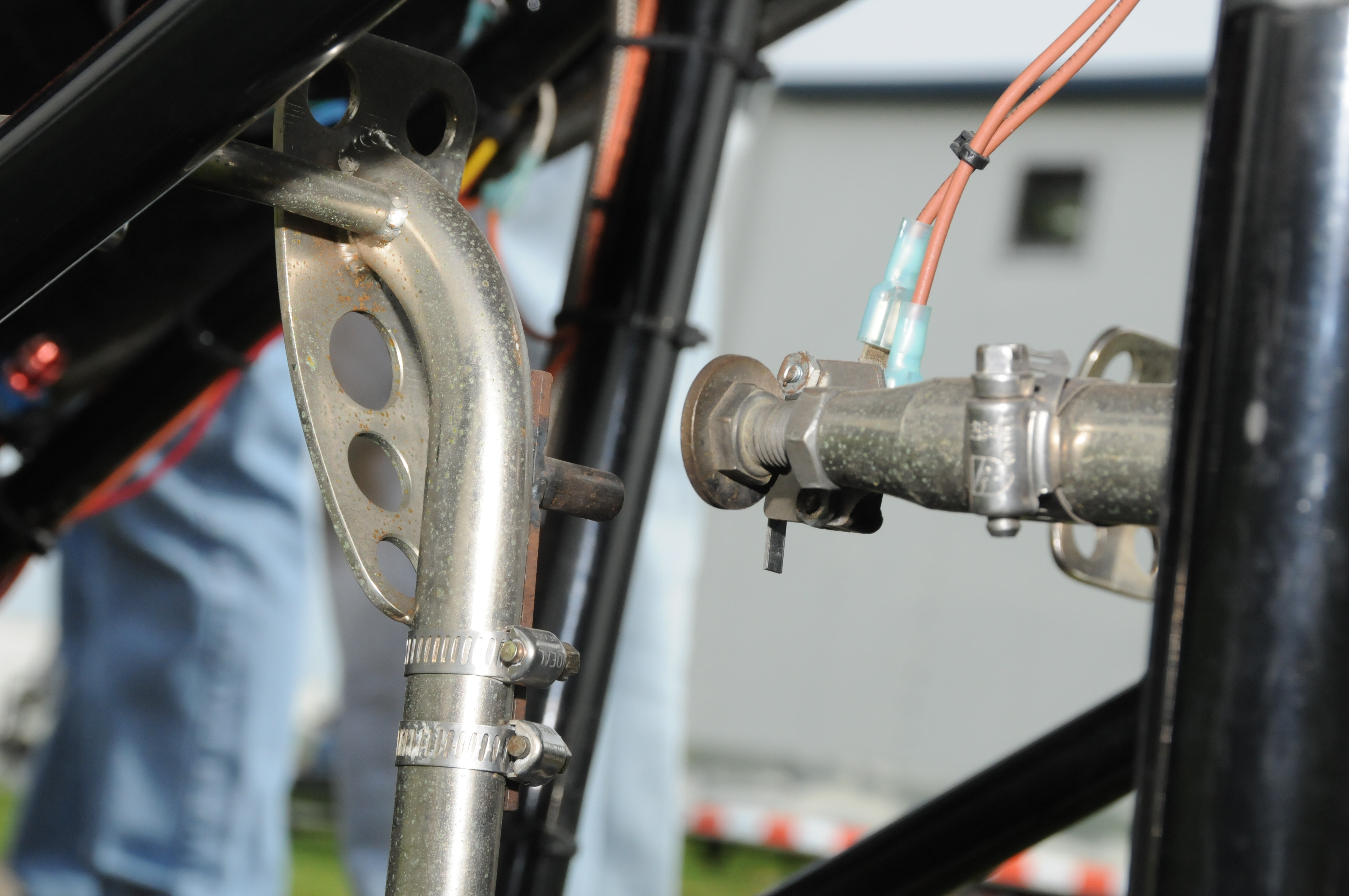

In the very early days of the class, the term of a throttle stop simply meant a bolt under the gas pedal to limit carburetor opening. That however, caused an issue. While the limited carburetor opening slowed the car down, it also had an adverse effect on how much horsepower actually was fed back to the rear wheels which moves the car. That in itself had a debilitating effect on that all important reaction time.

One of the “cures” to leaving the starting line at wide open throttle yet slowing the car down was the use of a throttle stop which was activated by several methods closing the carburetor down slightly later in the run. The next “problem” was that horsepower was becoming easier to “buy.” In the case of Super Gas cars on the 9.90 index, cars were built to run in the mid-nine second range. With cheaper horsepower, racers were showing up with Super Gas cars capable of running in the low nine-second range and even faster. With throttle stops only coming on later down track, it was becoming harder to slow the car down enough to run on the 9.90 index.

Through his Dedenbear Products company, Dennis Reid; and a couple of other companies; had been building delay boxes. In about the late ‘80s, some enterprising racer decided to turn the throttle stop on immediately after leaving the line, having the carburetor go to wide open throttle shortly afterward. “We were doing custom timers,” said Reid, “where we rewired a delay box to operate backwards to run the throttle stop. It wasn’t long before others began doing the same thing.”

The most effective way to “slow a car down” is to interrupt the power initially before the vehicle has picked up speed. Once speed takes over, it’s harder to stop a moving object. An example of this would be that if you were to shut off the power for exactly one-second after leaving the starting line, the car would slow down by X-amount. Shutting the power off by the same one-second prior to the car reaching the finishing line, would only slow the car down by way less that X-amount.

That’s why the car looks like it breaks after leaving the line and then comes back to life. In this manner too, the car runs a rather fast mph in relationship to the elapsed time. As an example, an 8.90 car would typically run in the 150-mph range, while today’s 8.90 Super Comp car runs anywhere from 170 mph and more. There remains a very small number of racers who will still utilize what is termed as a top end stop, often running mph in the 120 range.

The beauty of the higher mph is that the race is usually played out in front of you, alleviating you having to turn your head and judge when your opponent is coming down on you. But it’s that “break at the starting line and comes back to life” thing which confuses some. It’s a lot easier to understand handicap racing; although that in itself can be intimidating to the average spectator; when both cars chase after one another at wide open throttle.

“Say what you will, but throttle stops have truly ‘ruined’ some aspects of drag racing,” says veteran journalist Jon Asher. “Since almost no announcers ever explain what’s going on, spectators new to the sport are completely turned off by watching cars appear to come to a complete stop during a run. And — most importantly — it’s boring as hell to watch.”

It’s been easily said the fans don’t understand the concept. However, in most cases, any of the sportsman classes were probably never meant to be spectator-driven. They are mostly participant-driven and as such, as long as they are populated by participants, they will live on. But there are some caveats to the concept of the super classes.

“When I bring friends to the races and introduce them to drag racing,” says Division 5 Super Comp Donald Leisdon, “almost every time we watch the super classes they would ask ‘is that car having problems?’ After 45 minutes of explaining what the cars are set up to do, they would say ‘why would you spend all that money to go faster and then slow it down?’ My point is people want to watch full throttle racing like Top Dragster and Top Sportsman.”

The real point of it is that the classes were set up exactly as they still are today. The goal is to accomplish something; in this case turn on win lights; that is extremely difficult under the rules. The super classes allow for a person to compete without the concern of being “out-dollared,” in much the same as bracket racing. The onus is on the driver and not who has the most money.

The competition in the .90 classes is the only thing that keeps me in Super Comp,” says Doug Doll. “Damn near everyone at a given race has the ability to win which makes it both appealing and frustrating at the same time. I just wish we could throw a little bit of a curve to it. All of a sudden it would be a thinker’s class again.”

As for the “curve,” the indexes in the super classes have remained the same (10.90, 9.90 and 8.90) since they began some 30-plus years ago.

“The ‘problem’ with super class racing is that when conceived, horsepower to run 9.90 or 8.90 was not easy to build or cheap,” says veteran super racer Tom Goldman. “It was a challenge that many of us embraced and rose to. With the advent of modern cylinder heads, cranks and blocks, anyone can build an engine capable of horsepower that Pro Stockers have. NHRA failed to adapt the classes to the increased power at racers disposal. While other sportsman classes, Comp, Super Stock, and Stock experienced similar explosions in horsepower, their class Indexes dropped accordingly while the super classes were left alone. The time to lower the .90 indexes is LONG overdue.”