DRAG RAGS 1965: TERRY COOK TELLS HOW THE WEEKLY SAUSAGE GOT MADE

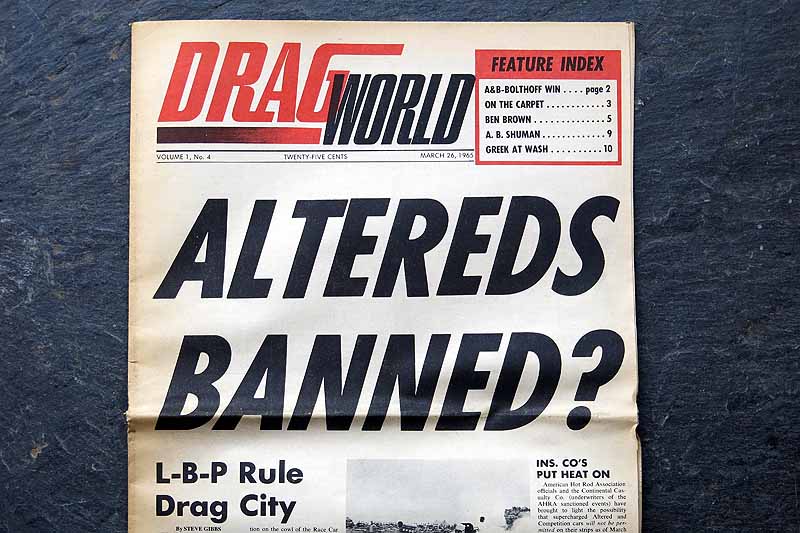

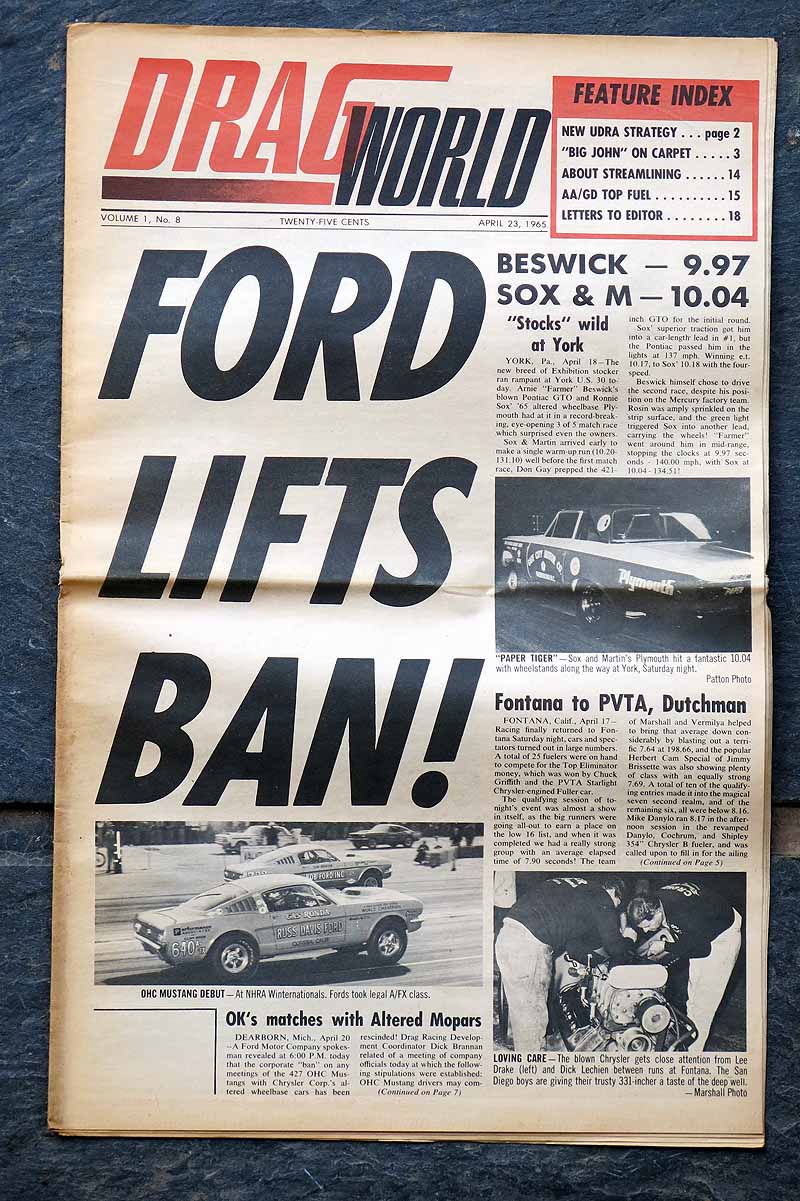

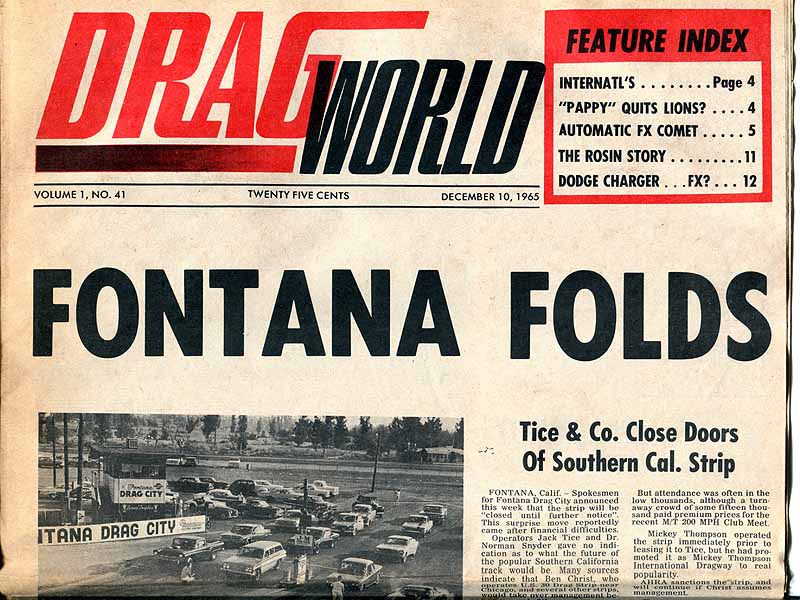

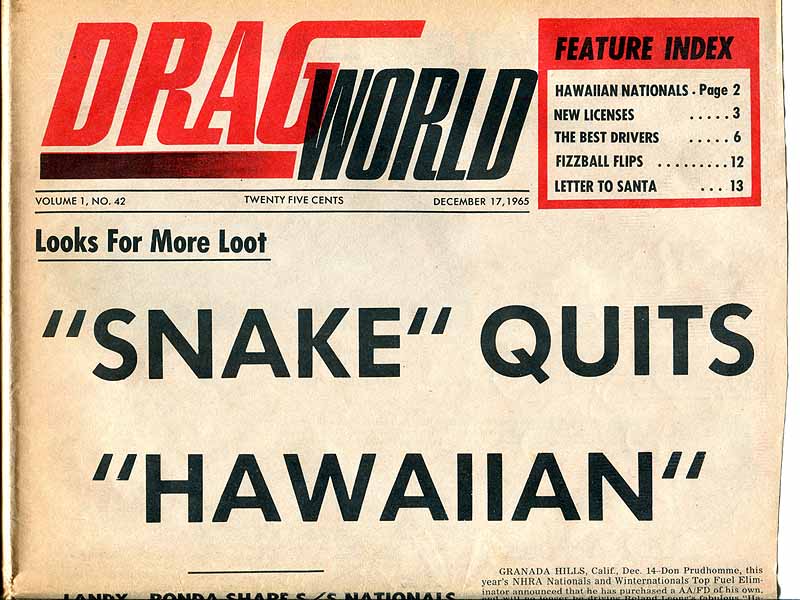

Before we pull the 'chute on 1965 and continue down our chronological quarter-mile to the '66 season (coming next time), let's veer out of the groove to pay homage to the short-lived Drag World newspaper. Drag News was far fatter, and Drag Sport Illustrated delivered finer photography on brighter newsprint, but Drag World's modern design and overall production quality scared its two older rivals into upping their respective games before flaming out as an independent publication in its second year.

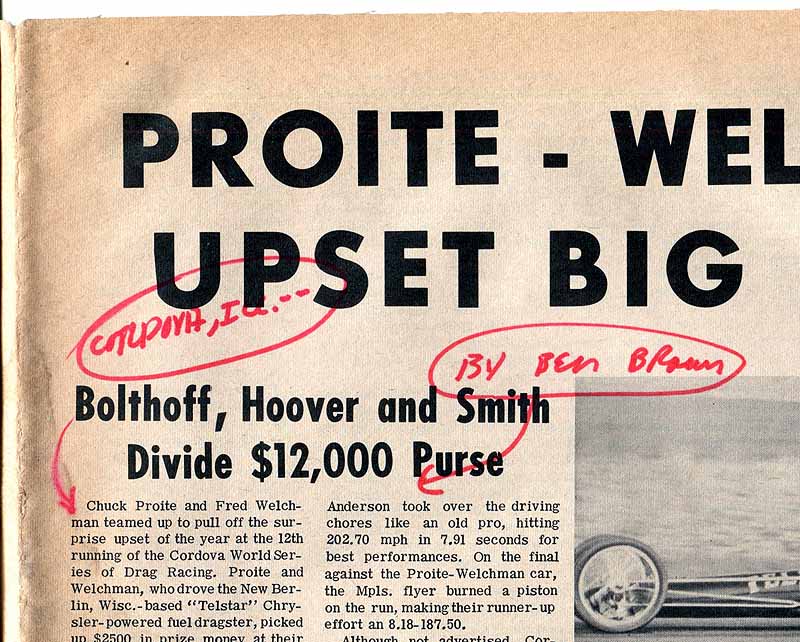

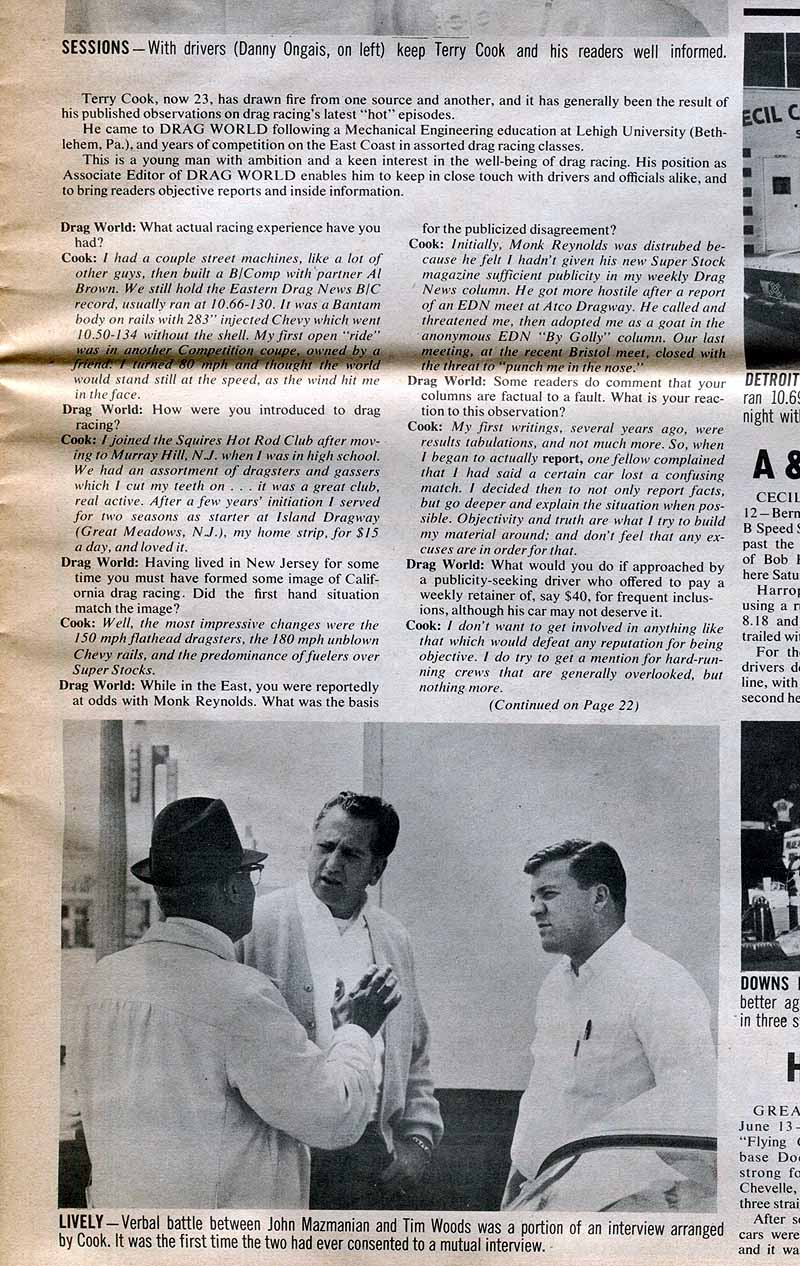

Among the personal back issues retrieved to research two prior 1965 installments of this series were two editions marked up in red ink (as seen in the accompanying clippings). One edition's notations indicate individual editorial payments owed to freelance photographers and columnists. The other issue is filled with text corrections of mistakes missed during that week's rushed production process. Thus did we suspect that both issues originally belonged to publisher-editor Mike Dohery.

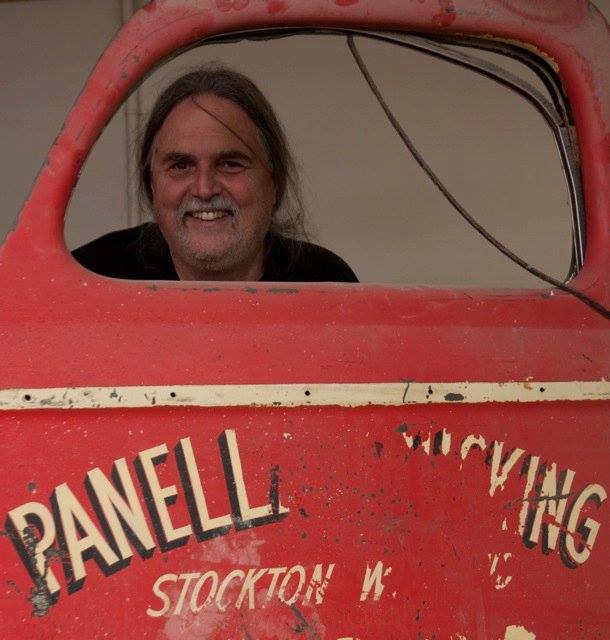

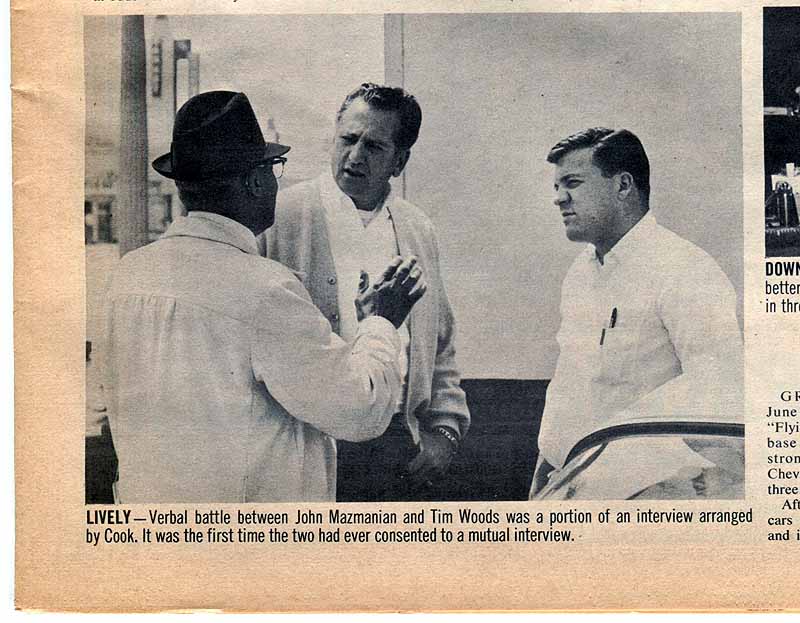

Four years ago, sample scans of both marked-up issues went 'cross-country to Drag World's original associate editor for comment in the March 2018 print edition of Drag Racer magazine (RIP). Sure enough, Terry Cook recognized the handwriting and high editing standards of his late boss and main mentor.

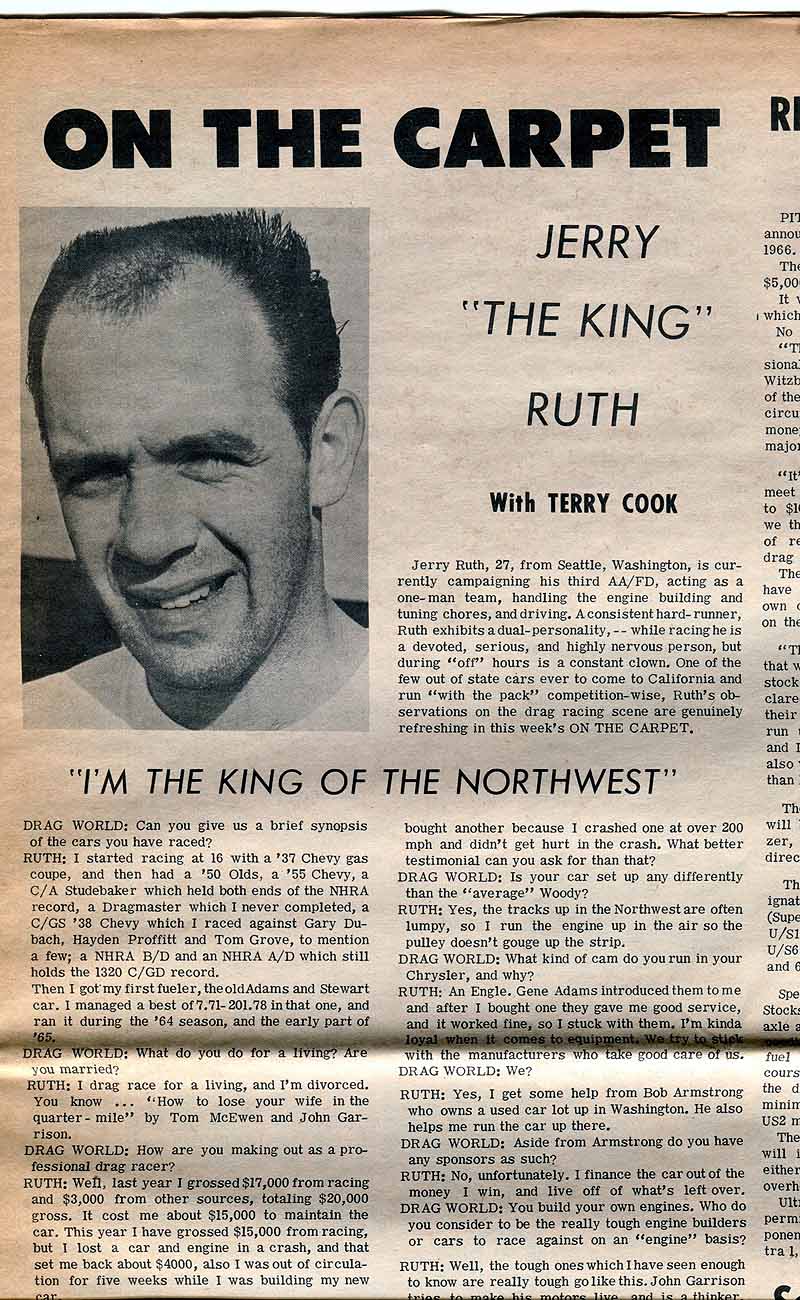

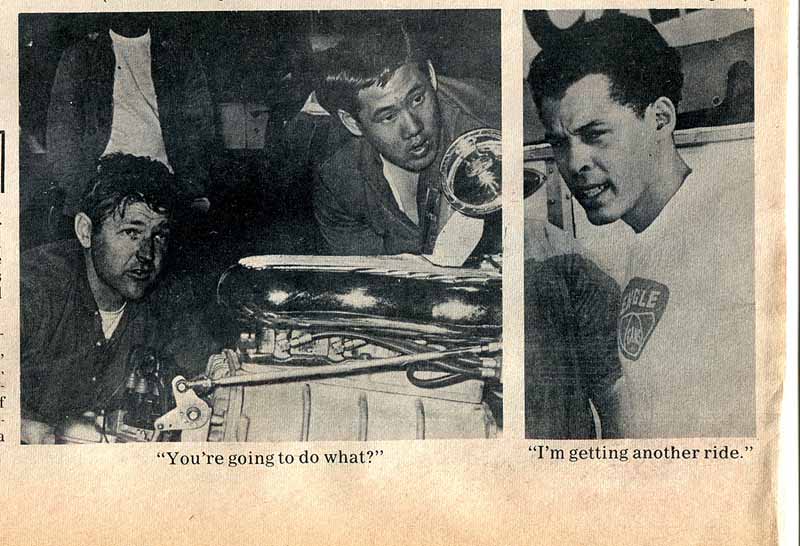

Once we got Cook e-mailing, we couldn't resist asking follow-up questions about the week-to-week operations of a typical drag rag of 1965. We've edited excerpts from those written conversations into the modern version of Terry's own "On The Carpet" interview series of 1965-66, before the proudly-independent title was acquired by AHRA's Jim Tice and neutered into the sanctioning body's house organ.

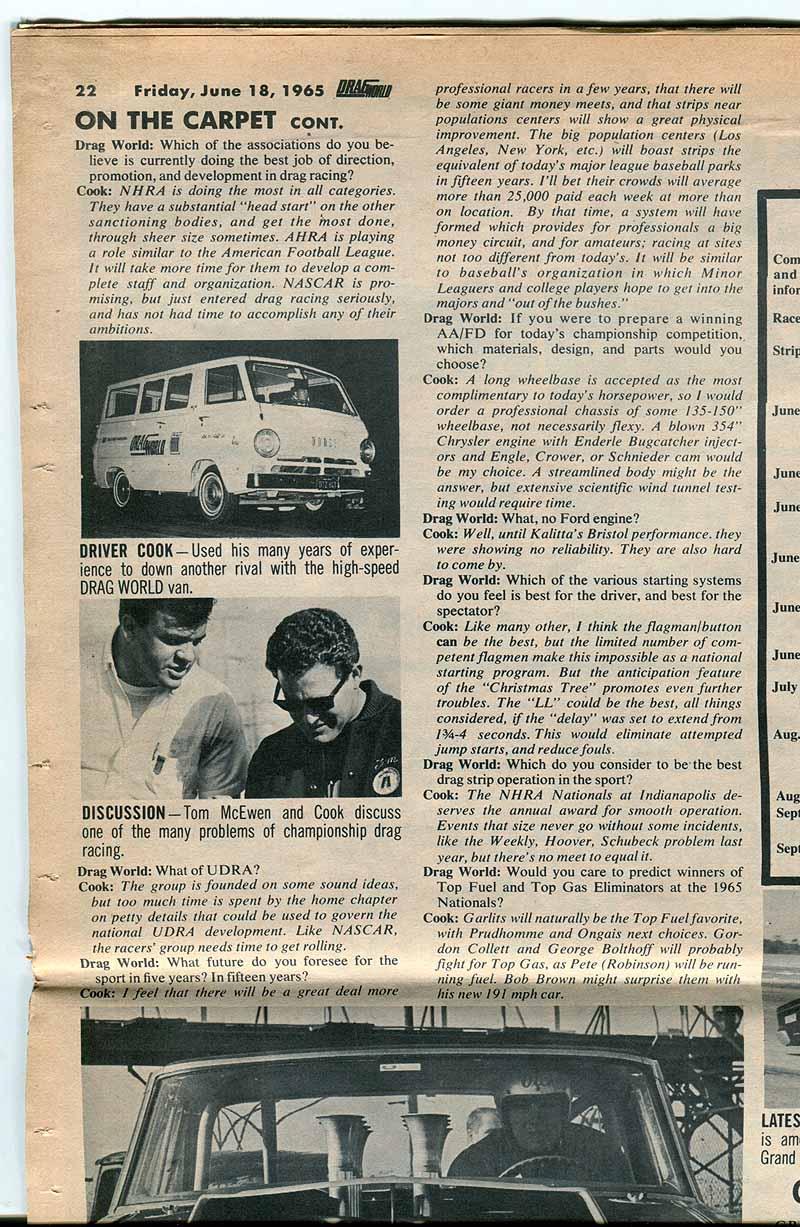

Terry Cook's name simultaneously fell out of the newspaper's masthead, only to resurface in the Dec. '66 Car Craft. He graduated to CC editor in 1969, then took over Petersen's Hot Rod flagship in 1972 before quitting California and the industry's top job in his early 30s. Now pushing 80, Cook recently retired from subsequent, simultaneous careers producing fiberglass custom cars (loosely based on 1930s classics) and Lead East, the New Jersey show that he ran for 35 years.

DAVE WALLACE: How did your journalism career get started?

TERRY COOK: I had a weekly Drag News column, "New Jersey News." I started it for free, then I got $5 per column, then $10, then $15. I was out there [in L.A.] at Lions one night and met Mike Doherty. He had read my shit in Drag News and offered me a job. I flew home, sold my C/Dragster, bought a 1960 Pontiac for $750, threw everything I owned in the trunk, drove 'cross-country, and started what has been a totally enjoyable and rewarding career and life. It was pure luck and fate that I had come to California just when Mike was starting up the publication.

DW: Did Doherty own Drag World?

TC: No, the original owner was Brainard Mellinger, who traveled the world importing cheap junk to the USA to sell retail. He ran ads in the Los Angeles Times seeking people who had schemes to make money. Mike saw the ad and sold him on the idea of Drag World. After the first year or so, when we were still not making a profit, Mellinger told Mike to sell it. Our second owner was Gil Kohn. After another year of not making money, Kohn arranged to sell it to Jim Tice of AHRA. Mike told me I could move to Kansas City with the paper. Luckily, I heard there was an opening at Car Craft.

DW: Describe a typical workweek at a drag rag.

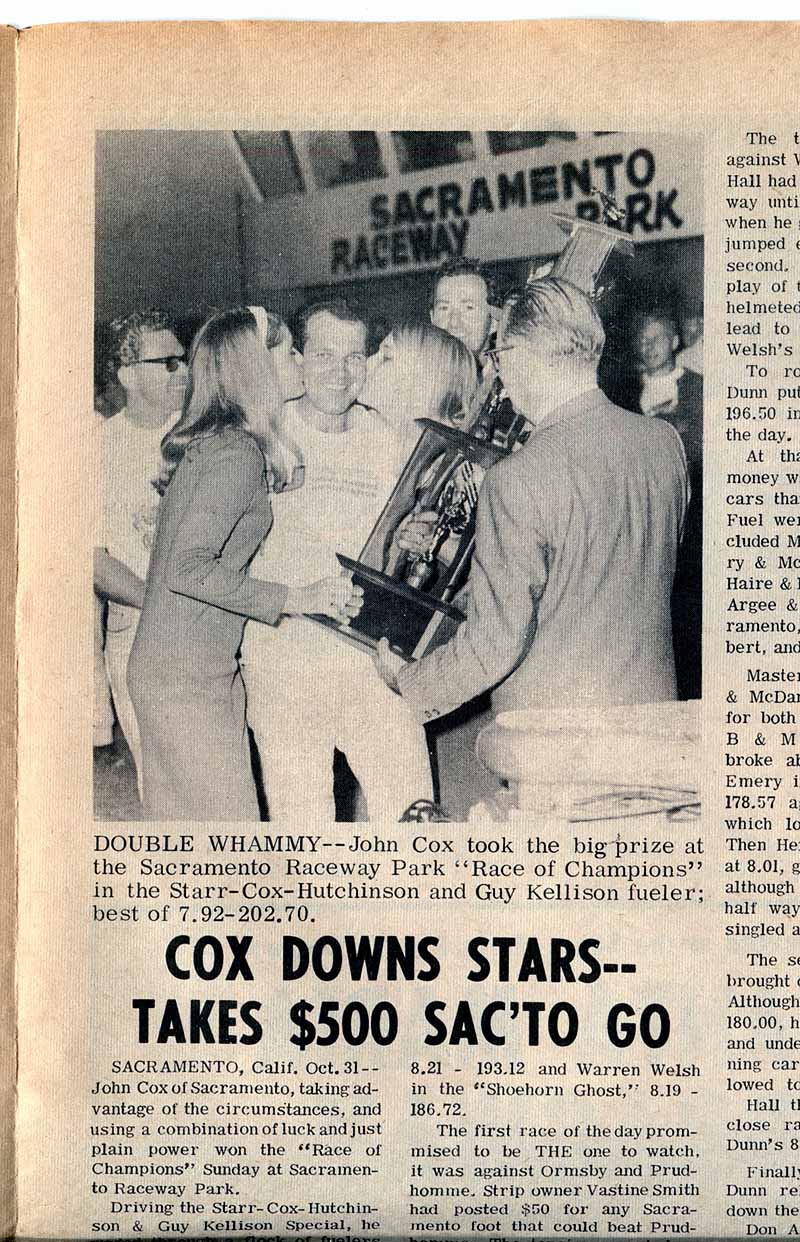

TC: I'd go to two or three tracks most weekends: Lions, Irwindale, San Fernando. Once I added Carlsbad on a Wednesday night. I'd come to work Monday morning, write my column and do whatever needed to be done to get the paper out: write captions, work on the "dummy" [mockup of what story and ad went where —Ed.]. Mike edited all the copy. The photographers would come by the office every Monday with stacks of photos. Doherty would usually make the selections. We worked until at least 10 p.m. Mondays. Tuesday started at the office, then went to the printer to oversee paste-up, following our dummy. I proofread each page. The drag rags all went to bed on Tuesday night and were shipped to readers on Wednesday.

DW: How much you were paid?

TC: I started in 1965 at $10,000 a year [about $92,000 today —Ed.]. After three years, I had worked my way up to close to $12,000. Drag World covered expenses for an out-of-town race, like Bakersfield. I don't recall them reimbursing me for going out to Lions every Saturday night.

DW: Many media veterans still consider the original, 1965-66 Drag World to be the best-written national tabloid ever published. The paper seemed to be popular with subscribers and sell to fans at tracks. Why do you think Drag News and even Drag Sport Illustrated lasted longer as independent tabloids?

TC: There never was enough ad revenue for us or DSI to compete with the two major, established players, Drag News and National Dragster. Drag News was packed with ads because Doris Herbert paid Don Rackemann some incredible commission, supposedly 35 percent or more. Drag News was always a schlock rag, journalistically, but Rack was a fabulous salesman. We never had a salesman other than Doherty, who was always busy helping put out each issue.

DW: Drag World was also controversial at a time when bad news was downplayed or altogether ignored by most publishers "for the good of the sport." Do you think that a reputation for sensationalism hurt its chances in such a conservative environment?

TC: From the start, Drag World was a class act journalistically. Issue Number One had the story about Petty's Barracuda crashing into a crowd; an accident that other publications never mentioned because National Dragster never reported on driver deaths or any other negative news. When somebody died, the only way the drag-racing community across the nation found out was by the black condolence ads that you might see in Drag News; not allowed in Dragster. The Petty story on the front page of our first issue immediately branded Drag World as a “scandal sheet” in L.A., which of course was bullshit. It was a real newspaper, like the New York Times, that was factually reporting the news, but many dunderheads in drag racing were so totally ignorant of life in the real world, they spread the scandal-sheet slur. Most likely that came from Rackemann and/or from the NHRA offices, now that they had a serious competitor. National Dragster is a house organ, not a real newspaper, and Drag News was mush.

DW: You graduated from writing a free newspaper column to running Car Craft, then Hot Rod, in no time, then walked away from a career in your prime. How does that time in the publishing business look now, four decades further down the road?

TC: I was blessed to work at Drag World and Petersen Publishing Company at the time I did. It was a magic, golden era, the best and most-creative 10-year period of my life. I had editorial freedom with a minimum of interference from "chicken blowers" [an enduring nickname that Cook coined for ad salesmen and publishers —Ed.]. Drag racing, as we knew it, and our memories of it, are going the way of the buggy whip and rotary telephone. We were blessed to live through that glorious era when dragsters smoked the tires on purpose. Now, with the USA and the entire world going straight down the shitter while the youths of America are only concerned with taking a selfie of themselves in their new, stubble-faced look of a bum beard, I'm just trying to squeak out a living and survive perhaps another healthy 20 years of existence.

incomparable collection of streamliners.

Terry might have a few left; pester him via decorides@aol.com.

To enlarge font for captions - Hold down CTRL button and push down + symbol on the numbers bar. Each time you press the + it will increase font size. To reduce size, hold down CTRL button and press -

PREVIOUS DRAG RAGS

THE EARLIEST EDITIONS

BANS WERE BIG IN '57

ISKY STIRS THE POT IN 1958

DRAG RAGS OF 1960 – TRAGEDY, POPCORN SPEEDS AND A CAMSHAFT RIVALRY

DRAG RAGS OF 1961: CONTROVERSY STALKS NHRA

DRAG RAGS: 1959 - GARLITS GOES FROM ZERO TO HERO, TURNS PRO

DRAG RAGS: 1959, PART 2 — HOW THE SMOKERS BEAT THE FUEL BAN

DRAG RAGS OF 1962: GARLITS IS NO. 1, WALLY IS ALL GAS

DRAG RAGS OF 1963: FUEL IS BACK - OR IS IT? JETS RUN WILD

DRAG RAGS OF JAN.-JUNE 1964: INNOVATION WITHOUT LIMITATION

DRAG RAGS OF JULY-DEC. 1964: ZOOMIES PUSH THROUGH THE 200-MPH BARRIER

DRAG RAGS OF EARLY '65: EXPLOSION OF WEEKLY PUBLICATIONS

DRAG RAGS OF JULY-DEC 1965: FUELERS, FUNNIES AND GASSERS APLENTY