ENCORE: RALPH SEAGRAVES: THE MAN WHO TOOK DRAG RACING TO THE NEXT LEVEL

Originally published May 2020

His name is rarely is mentioned when talk focuses on those who have advanced drag racing. It was 45 years ago that a corporate executive named Ralph Seagraves took drag racing to another level when few could envision there was such a destination.

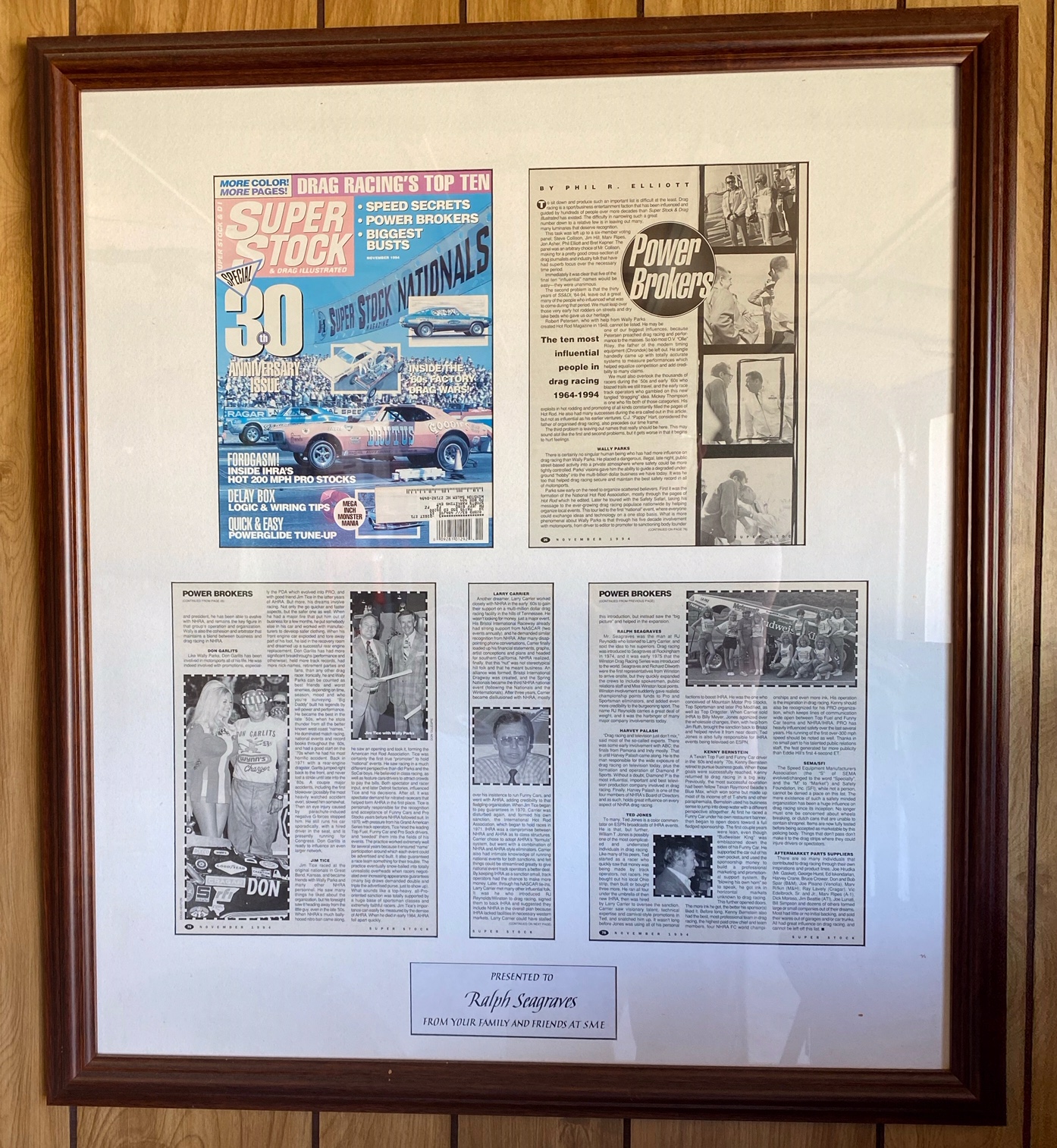

Seagraves was the president of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company’s Special Events Operations, later renamed Sports Marketing Enterprises, and was responsible for providing drag racing with its first major points fund sponsor.

Seagraves enabled drag racing to become a professional sport for more than just a select few drivers.

Seagraves and his team at SME also succeeded at a once-unbelievable task; i.e., uniting most of the American drag racing scene as one.

“Ralph Seagraves’ involvement is that unlike anybody else in the history of the sport. He covered all the bases,” explained noted drag racing historian Bret Kepner. “He took the entire sport to the next level, not just a single association. While the American Hot Rod Association was still in business in 1974, it was the IHRA and the NHRA that combined made up the bulk of sanctioned drag racing. And Ralph took both of them to another level.

“By putting those two entities who could never work together in any other scenario under one umbrella, so to speak, they were able to do monumental things because of Winston’s corporate direction. By corporate direction, and not taking away from anybody who was doing the job prior to Winston’s involvement, but Seagraves gave drag racing a press crew that we never could have had on our own.”

Drag racing can thank NASCAR racer Junior Johnson for this. Johnson got the ball rolling for R.J. Reynolds when he approached Seagraves for a sponsorship. Seagraves said that RJR was interested, but that the expenditure wouldn't put a dent in their advertising budget; that they needed to do something larger to justify the funds that he had to spread around. Johnson set up a meeting with NASCAR's Bill France Jr., and RJR wound up sponsoring NASCAR premier Cup series for 30 years.

Then followed Larry Carrier, founder of the IHRA and a NASCAR track owner, who used his connection from his Bristol Motor Speedway, to inspire Seagraves to take notice of the straightline style of racing.

Let the record reflect that the IHRA signed the first points fund program with RJR. Then-IHRA Vice President Ted Jones witnessed the first steps of drag racing's elevation.

“There’s no question, he really elevated it,” Jones said. “He was still trying to get it up more to a level of NASCAR, and, of course, it never did reach that level. It probably never will.”

However, it wasn’t because of a lack of effort.

Carrier understood the gravity of the situation. At the time, his IHRA was much like NASCAR in that its base was primarily in the Southeast with forays into the Midwest and Northeast. The West Coast-based NHRA encompassed a portion of each region.

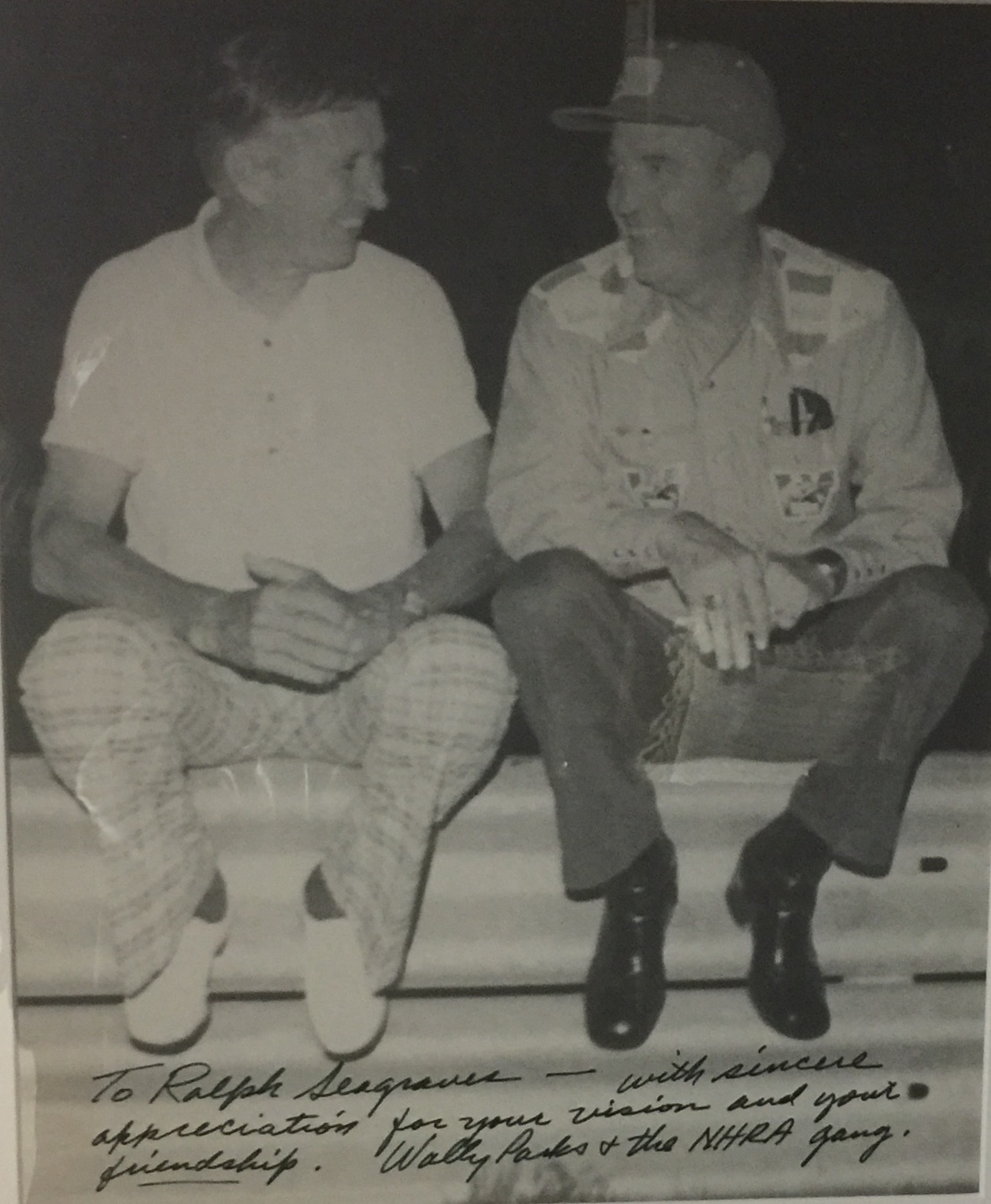

Carrier knew R.J. Reynolds' potential needed to reach well beyond the IHRA’s borders, and he recommended Seagraves reach out to his rival, Wally Parks, and the NHRA to complete the makeover of drag racing.

The news of R.J. Reynolds’ deal with the four-year-old IHRA traveled fast.

“I know this, I know Bill France called Wally Parks to get Wally to talk to Ralph about Winston getting into NHRA drag racing,” Jones said. “I know that because he publicly said that when he was inducted in the Hall of Fame.”

A source close to the situation told CompetitionPlus.com that Parks was satisfied to allow Brian Tracy, his marketing director at the time, to handle the sponsorship duties. What Parks didn’t understand was the magnitude of the program Seagraves had in mind.

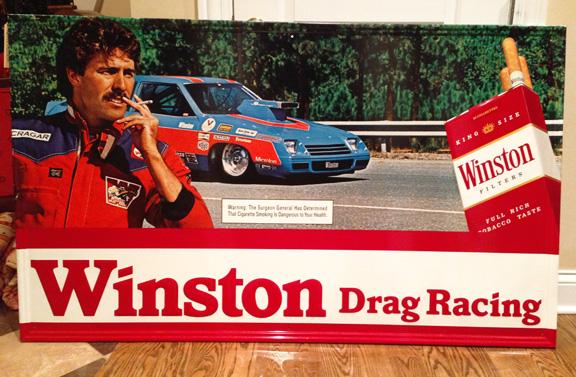

What Seagraves envisioned wasn't IHRA drag racing or NHRA drag racing, but Winston Drag Racing.

“Seagraves gave drag racing a voice that didn’t necessarily come strictly from Bristol, Tennessee, or from North Hollywood, California, which is where NHRA was at the time,” Kepner said. “It just came from drag racing. And for a brief period there -- until Carrier and Parks really started going at it tooth and nail, each trying to keep their part of the Winston pie -- until that happened for a very brief time, drag racing was almost completely unified.”

The unification wasn’t necessarily peace in the Middle East, but it sure resembled it, at least in drag racing terms.

“I don’t mean that Wally and Larry were on the phone joking,” Kepner explained. “What I mean is there was NHRA drag racing, and there was IHRA drag racing, but together they were Winston Drag Racing. The average fan didn’t know the difference. Winston became so locked into the image of drag racing that when the average fan saw a Winston drag racing sign, I don’t believe for a second that they questioned which one it was. They didn’t care. It was Winston Drag Racing.”

All of a sudden, this new direction provided drag racing with an inside track for media exposure once believed to be out of reach.

"Winston would buy a third of a page ad in all of the major daily newspapers we went into,” noted former NHRA press and publicity director Steve Earwood. “This was in the time when newspapers were king. If you had those local newspapers covered your event, you reached everybody. This drew in the television networks because they had to cover whatever news the papers delivered. It wasn’t rare to get the three major affiliates in each market.”

The advertising of cigarettes on television was banned April 1, 1970. That didn’t stop R.J. Reynolds from circumventing the regulation by elevating drag racing’s television presence.

For the most part, drag racing’s TV exposure was limited to the annual broadcasts of the Winternationals in Pomona, California, and the U.S. Nationals in Indianapolis. ABC’s Wide World of Sports carried the events.

In 1975, Diamond P Sports presented a harbinger of things to come with a rare production of the World Finals. A year later, Diamond P produced three events for syndication. IHRA first entered the TV field in 1983, and made its mark two years later on ESPN, when the fledgling network had fewer than 10,000 subscribers.

TV and media was the first line of attack in Seagraves’ aggressive approach.

The second wave was to literally paint the sport in Winston red and white. With a television and media plan firmly in place, Seagraves focused his efforts in a unified approach to branding hundreds of smaller drag strips in the Winston Drag Racing approach.

“Ralph and RJR had track improvement money for the major event tracks,” Jones explained. “They had a paint program where any drag strip if they painted it red and white Winston colors and kind of a Winston theme, red, white, red and everything, they could get free paint. And I mean they would ship a truckload of paint into the drag strip for them, but they had to paint their guardrails, their buildings and everything. That was the free deal. And the building was red, white, red, like a pack of Winston cigarettes.

“They actually went to the sanctioning body, and the sanctioning body had to recommend it and say this is what we’d like to have from Winston. A lot of them got scoreboards that didn’t have scoreboards, remodeling of the tower, and there was so much he was instrumental in doing for the tracks.”

Seagraves’ program didn’t just one-up the soft drink battle style of product placement in the early 1970s; it three-upped it.

“The one thing Coke and Pepsi did was if you used their product in your concession stands, if you cut a deal with the local distributor, the national Coke and or Pepsi company would send you brand new signage,” Kepner explained. “I don’t mean a nice Coke sign for your guardrail. I mean a brand-new electric sign for your drag strip that you put out by the road. Now, of course, it had a Coke or Pepsi soft drinks on the side of the sign. But who cares, right?

“When you saw one of those Pepsi or Coke signs, you knew -- especially if you were a kid and saw one of those signs -- it was like, “Oh, yeah, there’s a racetrack.” And of course, every track took them up on it.”

The Winston track program certainly put these tracks in a new light, regardless of their size.

“When you saw a Winston sign on the side of the highway, chances are it was advertising a race,” Kepner continued. “But either way, if it wasn’t a billboard, an actual sign, it was for a racetrack. So what Ralph gave the racetrack was a complete sprucing up, almost their own sponsorship deal. It made the track look that much more professional. And it certainly made the little tracks look like they were a part of a bigger deal.

“Yeah, it was just a complete transformation. Everything became red, white. But Ralph went to the tracks and said, ‘We’ll pay for it. We’ll spruce the place up. We’ll give you oil barrels that are painted red and white for trash cans. We’ll give you banners, we’ll give you signage, whatever you want, just tell us.”

Kepner isn’t so sure a few unsanctioned tracks didn’t get in on the deal as well.

“If Mom and Pop had a small drag strip, all of a sudden if they took full advantage of Ralph’s deal, the fans would come in and say, 'Wow is this place going to have a national event or something?' It became a Seagraves legacy. Because to this day, 20 years after tobacco was completely extricated from the sport, you can go to many racetracks and they’re still red and white.”

Seagraves and RJR required the teams to run their decal as part of the sanctioning body agreement. It was part of the Winston “contingency” plan, an unadvertised fund some joked was paid in untaxable money.

“The one thing those stickers represented was an absolutely astonishing amount of money that Ralph gave under the table to racers,” Kepner said. “I don’t think they actually paid contingencies. I could be wrong. I don’t think that sticker was worth anything in the winner’s circle. A lot of racers -- certainly a lot of pros -- went to Ralph and said, ‘I can’t make it to the next two IHRA races with my nitro funny car.' And Ralph took care of it.”

Seagraves was the kind of person who put more value into a relationship than a sponsorship deal. One usually fed off of the other. No one knew this aspect of Seagraves more than his son Colbert.

“That was one of the things that he instilled in everybody that worked in sports marketing. It’s not just a business association, it’s more of a friendship,” Colbert explained. “When you’re doing it with friends, you get upside down, but you can always talk it out, work it out if you’re friends. But if you’re just business acquaintance and it’s just business, sometimes when you get upside down it’s not so easy to get right-side up again.

“That was one of the things that he always taught me, and everybody else that worked for him was that you formed these relations, it was all about relationships. He wanted everybody to embrace R.J. Reynolds whether you smoked or not. Dad’s philosophy was, ‘We don’t encourage anybody to smoke. But if you do smoke, we encourage you to smoke our products because we support the sport.' ”

One of the more interesting friendship dynamics was the one Seagraves shared with Carrier. Rarely did they butt heads, but when they did, there was no mincing of words. Case in point, Jones recalled the time Seagraves brought up one of Carrier’s more controversial policies.

At the time, Carrier instructed the editorial staff of IHRA’s house publication, Drag Review, to black out non-contingency sponsors in photos and offer bonus points to those who ran only contingency posting entities. The policy would inevitably cost one "General" Lee Edwards, of the IHRA’s homegrown stars, the 1978 Pro Stock championship.

Carrier responded to Seagraves in a friendly manner: “You remember when we started this thing, how you said you’d never tell me how to run a sanctioning body and I, in turn, promised that I’d never get into the cigarette business? Well, I still haven’t made my first cigarette yet.”

Hall of Fame Pro Stock driver Roy Hill, whose 1980 Plymouth Horizon was used in R.J. Reynolds’ banners and ads, said that as much as Seagraves was a champion for the tracks, he was more so for the racers.

“Oh, he’d gather eight, ten people and take them to dinner,” Hill recalled. “I was always one of those eight or ten people. Anytime there was a TV show, he would come get me because most of the racers at that time couldn’t even talk to a wall.

“I owe so much to R.J. Reynolds. I’ve never forgotten them. You come in my shop, there are still banners. You go in my condo at Charlotte Motor Speedway, there’s a picture. You come in my office, there’s a picture of Ralph Seagraves hanging there. Ralph took us to the top of the mountain.”

There’s no doubt, as Hill recalled, the view from up there was second to nothing.

“It was tremendous,” Hill said. “When you look around, and then you realize you’re up there, it’s not hard to see they made everyone around them bigger and better. It just came natural to succeed.”

As multi-time Funny Car champion Dale Pulde sees it, Seagraves and R.J. Reynolds made drag racing family-friendly entertainment.

“Winston cleaned it up,” said Pulde. “They did the same thing in the Winston Cup in NASCAR. They made it more of a family-type deal. They made it good for the spectators.”

Seagraves retired in January 1985, and by the season’s end, R.J. Reynolds ended its relationship with IHRA. At the end of 2001, the federal government ended RJR's involvement of drag racing.

Kepner believes the writing was on the wall from Day One when RJR got involved in drag racing; that the massive engagement wouldn’t last forever.

“The reaction to tobacco advertising started early in the 1970s, but there was nobody in the business who can honestly say they didn’t see the total banning of tobacco involvement in motorsports coming a long way off,” Kepner said. “That deal was so big that the NHRA probably couldn’t be faulted for hanging onto it until, literally, the government pried it away from them.

“You have to remember that the points funds, even from the first year of Winston involvement, were massive in that final year compared to what they started out to be. I mean, Winston, yeah, don’t get me wrong. It was a mechanism of the increasing restriction for them to advertise it anywhere else. But it was still a money tunnel for Winston. I mean, they just kept spending more and more and more and more money because they had fewer and fewer and fewer and fewer places to advertise.”

The initial points fund for the NHRA started at $100,000 in 1975 and was $2.3 million when the association with drag racing ended at the end of the 2001 season.

Seagraves passed in January 1998 of a heart attack. His passing robbed drag racing of a tremendous fan of the sport and its personalities, and one who let his actions speak louder than words.

Sadly, today’s racing community isn’t what it was like when Seagraves championed for the next level.

“It’s a shame that things have gotten to where they’ve got today,” Colbert admitted. “Nothing against Coca-Cola or any of the other companies in drag racing today. I don’t think back when Dad was involved that the almighty dollar was the most important thing. It was still a sport and people still had that passion. And I think a lot of the passion has gone out of it today, and it’s more about the money than it is the passion and the sport of racing.”

Regardless of today’s atmosphere, there will always be those who lived in the so-called “good old days” who will remember a man named Ralph Seagraves. To them, he was a beacon of light for drag racing before anyone knew where the light switch was located.

“He had a lot of power in motorsports, and while it could have been easy to be a jerk, he remained still the nicest guy in the world,” Kepner said.

And with his appointment to multiple halls of fame, Seagraves proved nice guys can finish first.