Photos courtesy of Evan Smith, NHRA, Billy Glidden Collection

Few wanted to drag race more than Billy Glidden, the eldest of the two children of Bob and Etta Glidden. For as long as he could remember, he grew up working on his dad’s various Pro Stock teams, but he never wanted to be a crewman for the rest of his time in the straight-line sport.

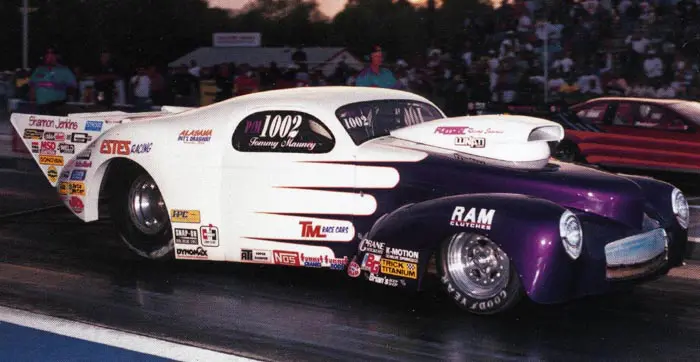

You are about to read how Glidden ended up in a small-tire Mustang that dominated the arena like his elder did in Pro Stock for decades. Sure, he raced on the NHRA Pro Stock scene before this, but this entry set the stage for him to succeed against the odds.

Glidden only needs to look at the black Mustang in his Whiteland, Ind.-based shop to remember the car establishing his mettle as a drag racer.

He traces the inspiration to a moment in 1983, while steering the Ford EXP his dad drove in 1982, as it was towed to a body shop in town. Glidden admits many thoughts were running at breakneck speed through his mind of the opportunity ahead of him.

Glidden was to drive the EXP at the 1983 NHRA U.S. Nationals in Indianapolis in one of the highest-guarded secrets in drag racing. The anticipation of lining up alongside his drag racing hero Bob Glidden, Lee Shepherd, or Frank Iaconio, was more than he could have imagined. Finally, the kid who had studied intently from standing behind his father’s car would get his shot.

Glidden was unlicensed, but he didn’t imagine the process overly complicated since he had been around the class for as long as he could remember.

As soon as he arrived at the body shop, Glidden learned his father had sold the EXP.

“Punch to the gut,” Glidden admitted. “It became increasingly clear that my role was to be a crewmember, not a driver. I was supposed to get a car to race all those years, but I never did. I learned quickly on that day that if something was going to happen for me to drive, I would have to create my opportunity.”

Fast forward 11 years, and Glidden finally got his shot to drive a Pro Stocker.

Bob had a new Pro Stock Mustang he was testing in early 1993 at Houston Raceway Park, and Billy and his wife Shannon came out to help the elder Glidden with his new ride.

“He called and asked us if we’d come to the racetrack and help him,” said Glidden, who was living in Houston at this time. “So we went out there for three days. And on the last day, he says, ‘Well, this is the last run I will make. After I make this run, you want to drive the car?”

“I didn’t hesitate, I said, ‘Yes.”

Bob had run a best of 7.37, 191 mph in the testing.

Billy’s first run was a 7.32 at 191. Bob changed the carburetors and the car slowed by .01, still .04 quicker than the car had run in the previous two days.

Armed with confidence and now experience at driving a Pro Stocker, Glidden landed a driving gig with team owner Harold Stout a year later.

Glidden was driving a five-year-old Ford Probe when he made his Pro Stock racing debut at the NHRA Atsco Nationals in Phoenix. He qualified No. 8 and beat his father in the first round, also carding the low elapsed time of E-1. He then stopped Warren Johnson in the second round, before his Ford rolled the beams and fouled against Jerry Eckman.

Two races later, Glidden reached another semi-final round, but not before stopping the seemingly unstoppable Darrell Alderman, all the while running a 6.99, to become the fourth member in the Holley Six-Second Club.

Stout pulled the plug on the program in mid-1994. Glidden returned to the family team to drive a second car, but at the end of 1995, following a cloud of NHRA Pro Stock controversy, yet with encouragement that Ford would renew the team’s deal on a three-year program, instead moved their marketing budget to John Force Racing.

After Pro Stock racing for over two decades, and at the time the winningest racers in the class, the Glidden family sold the operation and was out of drag racing.

Once again, Glidden found himself in the same position as 1983, but this time with no professional prospects on the horizon.

That’s when the beater Mustang that he raced on his rare weekends off since 1992, and crashed in 1997.

He then transferred over to his famous black Mustang, which he won every time it went to the track in its early years. Glidden’s presence on the relatively hobby scene didn’t endear him to those competitors who labeled him as a professional drag racer.

“All I had working in my favor was an extensive background, with plenty of experience,” Glidden admitted. “I had a smaller engine and a clear knowledge of how to bring the race track to my car. I was just fortunate to have learned how to manipulate racetracks.”

Of course, Glidden’s blunt and to-the-point demeanor didn’t help the matter when he pointed out that he was just a better drag racer than they were.

“I heard a lot of bad things, ‘Well, you’re a professional,” Glidden recalled. “How in the hell am I more of a professional than you? You’re spending 20 times what I’m spending. I rolled into the track with a single-car pick-up with a 24-foot trailer, looking like the Clampetts on the Beverly Hillbillies.”

Glidden can remember a period of four seasons, during which the black Mustang was nearly unstoppable, whether it was racing outlaw small-tire races or in Super Street at the NMCA. It’s an impressive feat when you consider the roots of the Foxbody.

“That thing was built in the winter of ’89, ’90, and it was built for a guy to be able to run low 11s, and he wanted to run in the 10s,” Glidden explained. “So it was built for him to do that with. And he crashed it a couple of times, believe it or not. And then I drove it for him. His father was a very, very successful businessman. He was into furniture and trucking, and the son was an only son, and he didn’t want him to get maimed by a race car.

“I’d say a few years after I had driven that car, the father died. And before he died, I had crashed our old beater car, the multicolor car we had and bought [the Mustang] from them because the father in his will put it that the son wasn’t to drive a race car or he’d lose his inheritance.”

Glidden became the black Mustang-whisperer as he drove the car, originally intended for 11-second runs, to the reported first seven-second run in small-tire drag racing history.

“We won a lot of stuff with that old car,” Glidden recalled. “We raced it in 2019 a couple of times and we raced it in 2022 a couple of times. But that car was built to run into the high 10s and it’s still just like that. I’m 61 years old and if I had the same accident I had in 2017 when I crashed, it probably wouldn’t be as fortunate of a result.

“That car, just the way I made the last run in it in 2023, I guess we ran it just the way that was, it’d go 6.50, about 215, 216.”

Glidden used the car in a tire test and 4.9 in the eighth-mile and coasted to a 6.83.

Learning there’s a time to step away from the Mustang, just goes back to the life’s lessons Billy learned “Growing Up Glidden.” But those early years of racing the Mustang was about proving a point, and basically keeping himself in a racing world that had dried up for the family. But, not him.

“We’d outrun everybody in just 60-foot, most of the time, more than a tenth,” Glidden explained. In fact, most of the cars, we’d outrun .15 in just 60-foot. And that’s just because of what I grew up in. They’d say that my dad was doing everything for us and blah, blah, blah. My dad never helped us, ever. He didn’t help us. And they all said I was a professional racing against all these amateurs, yada, yada, yada. Well, I just kind of went with the flow and I said… I made comments that these people didn’t deserve to do what they’re doing and blah, blah, blah. But in the end, what people really didn’t understand was our paycheck was what we could win. That’s why winning was so dreadfully important to Shannon and I because that was our paycheck every week was what we could win.”

The Glidden mantra was always to make the most out of the least, and even during the championship seasons the family replaced money with work ethic.

“We were getting a lot more out of what we had than everybody else was,” Glidden said. “I didn’t rest on they’re all going to not get better at their combinations. And eventually they all did, especially the turbos and blowers. They just came out and started wailing on all of us. And the base engines that I run are my small blocks. They’re still the same engines, still the same blocks and heads. Still the same old junk.

If I stop and think about it for a moment, way back when, when we were going 7.80s and 7.90s and everybody else was going 10s and 20s and 30s, that was incredible.”

Glidden amassed four NMCA Super Street championships, and when he came over to the ADRL’s Outlaw 10.5, where he and Shannon won two championships, it was still about being overachievers.

“I didn’t get rear ends or transmission parts or old engine parts or anything from here, ever,” Glidden said. “Back when this was still Bob Glidden racing, I was told if anything of any of my racing ever hit the driveway in my car, I would be fired instantly.”

Glidden said his foundation was established in the latteer years of working with the family on the Pro Stocker. He worked on his own racing program in the early going, with clandestine trips to the junkyard for blocks and then did engine work in the living room of his house. None of his competition knew what they were up against because Glidden said he wouldn’t allow them close enough to his operation to see. His growing customer base was another story.

“We had a lot of customers,” Glidden said. “At one point in time, I was doing customer stuff, and those people who thought that what I had going on here was so dreamy, I’d tell them, ‘Well, you think it’s so nice, here, you just come and spend a week with me. Just come here, and I don’t want you to do any work or anything. You literally follow me around.”

“They stayed in our house, and they came to the shop, and they’d last two to three days. Every one of them, almost every single one of them that ever did, is still really good friends with us. And to the person, it was, ‘I don’t know how you live like this,’ is how they would say that. And we live tighter now than we did then.”

Glidden and Shannon live on such a budget that they reportedly asked the race series to give them the cost of the trophy in cash instead of trophies.

Glidden isn’t finished racing yet. He confirmed he’s got a Chevrolet Beretta in partnership with Mark Young, will be racing in the future, following a chassis update nightmare.

Then there’s a rumor Glidden has flirted with the idea of racing a Top Fuel dragster, where a team has also shown a mutual interest.

“Shannon and I are survivors,” Glidden said. “We have known for decades what it takes to win, and how to do it without truckloads of money. I think our success over time has proven that. Where there’s a will, there’s a way. That’s our motto, and if you ask me, a good one to have.”