Photos by NHRA, Norman Blake

Pro Stock hasn’t always been a simple formula. Today, those that participate in the class carry a common weight of 2,350 pounds in a two-door American made coupe no older than five years old with the source of motivation coming from an engine that displaces 500-cubic inches. Sounds pretty simple, huh? It has always been the nature of man to start with things in a difficult fashion and make it easier as knowledge and technology permit. Such was the case with NHRA Pro Stock as it took them nearly a decade to make the drag racing equivalent to NASCAR an easy proposition.

When the NHRA announced that they would be changing to a “mountain motor” format for the 1982 season, they were the last of the three major sanctioning bodies to abandon the small block Pro Stocks. The AHRA, whose rules had initially mirrored those of the NHRA inevitably allowed small blocks the use of nitrous oxide as they converted over to the mountain motor format a year prior to the NHRA’s decision to abandon ship.

It was no big secret that the NHRA technical department sought to make things simple in those days. Just prior to the U.S. Nationals, for example, they announced the disbandment of Modified Eliminator in favor of the more time-efficient Super Gas entries. There was a feeling the pounds per-cubic-inch format was living on borrowed time as well.

There were a few factors behind the decisions the NHRA ultimately made. The first was that maintaining parity among the brands in competition created huge headaches for all involved. At any given time, one manufacturer was always complaining that a rival competitor had an unfair advantage. Secondly, the IHRA’s mountain motored cars were stealing the media spotlight. Their stars, which included such standouts as Warren Johnson, Rickie Smith, Ronnie Sox, and Roy Hill were clicking off seven-second laps with relative ease while the NHRA’s small-block screamers were lucky to land in the 8.30s. The NHRA needed this thunder in the media, and swallowing their “NIH” (not invented here) pride decided to adopt a mountain motor variatuib of Pro Stock in 1982.

When Pro Stock was first introduced in 1971, the class was conducted on a pounds per cubic inch basis. Now for those who may be unfamiliar with that terminology, please allow us an opportunity to explain. For instance, if a Ford driver ran at a weight break of 7.0 pounds per cubic inch and campaigned a 351-inch motor, his car would have to weigh a minimum of 2,457. On the other hand, the Chevrolets might receive a 6.0 weight break and they would have to tip the scales at a minimum of 2,376 with a 396-inch powerplant. We’re not saying that was the exact scenario of weight breaks, but you get our drift as to how it was always a constantly changing formula. In other words, if you kicked butt on Sunday, you could get pencil-whipped on Monday for your accolades.

It’s interesting to note that today only Warren Johnson remains active out of all those who ran this style of Pro Stock.

Pro Street standout (later turned Pro Mod en gine builder) Pat Musi was also a frontrunner in that era.

“Back in those days, everyone built the smallest engine they could to get within their limit,” Musi said. “The rules adopted in 1982 simplified things. It was a challenge.”

One has to wonder if the NHRA knew how to regulate the class once they created it. In the years prior to the existence of Pro Stock doorslammers, racing was limited to running class, which in turn was regulated on a pounds-per-cubic-inch basis. However, within the various divisions, if a certain combination was rendered uncompetitive, the team could simply choose another classification within the eliminator. With Pro Stock, there was no such option. One had to live with the weight breaks afforded them, get another car, or quit. Depending on which way the weight breaks went, some of the drivers migrated into NHRA’s Competition Eliminator under the Altered or FX (Factory Experimental) designation or in Modified trim, under the Gas Coupe rules.

“There was a stink in the press that these factory guys would come in and run the sportsman ranks,” recalled former Hot Rod magazine staffer Dave Wallace. “The NHRA eventually took matters in its own hands and adjusted the wheelbases to discourage this process. I can remember the Martin Brothers out of Texas who adjusted their wheelbase to beat the rule.”

It wasn’t just limited to the Martin Brothers. Veterans like Butch Leal, “Dyno” Don Nicholson, Scott Shafiroff, Ronnie Sox, Bob Riffle, and Don Carlton often raided the sportsman ranks, seriously killing the morale in these classes. Their means of getting around the rules inevitably increased the cost of living in the sportsman classes. The common reasoning was that being uncompetitive in the Pro Stock class was replaced with the publicity attained by winning in the sportsman ranks.

With all of this shuffling around and indecisiveness on the part of the rules makers, one might think the method of maintaining parity among the big three was more of a headache than a challenge for the racers involved. One of the more prominent teams in this style of racing was the duo of Wayne Gapp and Jack Roush. The team won the 1973 NHRA Pro Stock championship, but it became evident when bringing up memories with Gapp that he was never a fan of this style of racing.

“It was a big headache,” recalled Gapp. “It was like a NASCAR race that I watched some years ago. They decided one brand of car needed to cut a quarter-inch off the rear spoiler, and then another ¾-inch. Back in those days, the NHRA started to do the same thing with the weight breaks. Once you start making compromises like that, there’s no fair way to make a rule. It didn’t make any difference if you were a Ford, Chevrolet or a Mopar, if you worked the hardest during the off-season, and you were the individual or the corporation that made the most horsepower, and then the sanctioning body changes the rules to slow you down, well, that’s bull****. That’s what happened with this deal.”

Frank Iaconio, who now builds engines for several of the current Pro Stock teams in competition, was a competitor in those days and more than held his own. The veteran driver captured four national event wins from 1978 until the last year of the format in 1981. He too, backed up Gapp’s opinion.

“It was more a headache,” said Iaconio. “I wasn’t really against it, but I think the 500-inch program ended up becoming better for everyone. This time you didn’t have guys complaining of the weight break. I wasn’t initially happy with the 500-inch rule, but I won the first race and that made me real happy.”

The reason that many of the teams were initially against the conversion to the common format is that they had invested a great deal of money and time into making their programs work. They spent an equal amount of the two just trying to maintain pace with Glidden, who was probably the most handicapped of all of the drivers. If you wonder why that is, then we can make it abundantly clear by pulling out the record book.

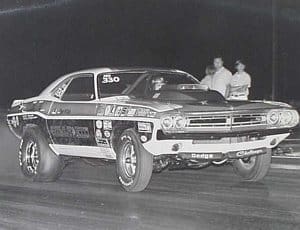

From 1974 to 1981, Glidden won 32 national events and claimed 5 world championships. It didn’t matter where he went in terms of manufacturers, the penalties followed. The not-so-odd thing is that the success followed as well. In 1979, Glidden accepted a deal from the Chrysler Corporation and that suited him just fine because the Chrysler Hemi was always considered to be one of the best suited motors for the class.

In just one year under the Mopar banner, Glidden conquered seven out of ten national events. He was into his second season when the company filed for a government bailout and ended their association. Just when it looked as if the other Ford racers had gained a reprieve, Glidden returned to the Blue Oval camp with a trusty Fairmont and fought tooth and nail with Reher & Morrison to retain his championship.

Glidden, while expressing frustration, never took it personally. He just found new ways to make his cars run fast.

“I didn’t look at it in frustration back in those days,” said Glidden. “I was just trying to survive. It looked really unfair to me from the outside, but we still ended up winning most of the races anyway. No one else in Pro Stock really had to deal with the rule changes as much as I did. In looking back, and any way you look at it, we still came out of it pretty well.”

Frustration and lobbying were always a part of the Pro Stock game until the end of 1981. It was as equally aggravating in the formative years as it was in the final one. Veteran journalist Jon Asher recalled the day when the Mopars decided to sit a race out.

“The pounds-per-cube theory was always in constant need of adjustment to make it fair for everyone,” said Asher. “I think the people who suffered the most in the earliest days of this format were the Chrysler Hemi cars. Chrysler was unhappy with the weight break that their team had to race with in Amarillo for the NHRA World Finals and they withheld all of the factory cars at that race. Without factory help, only one…maybe two…Chryslers showed up to race.”

Just how crucial of a statement was Chrysler trying to make? Back in those days, the winner of the World Finals was declared the World Champion.

The popular consensus is that the weight breaks were designed to handicap the Hemi engine’s success. Once we look at the NHRA’s demographics, we can understand their reluctance to let this particular breed of engine run rampant. The demographics in those days revealed that 85% of the attending fans drove GM products and the Mopars and Fords accounted for about 10% apiece. In an attempt to take advantage of the weight breaks levied against the Hemis, many of the racers would go through tech with a 426-inch cars destroked to a 396. While this combination remained competitive in AHRA competition, it failed miserably in the NHRA. Eventually it seemed as if the NHRA had given the Hemis the good riddance, but they never counted on the canted-valve Ford coming along. At the same time Mopar was getting beat up by NASCAR rules makers. They had already pushed the Hemi out of stock car racing.

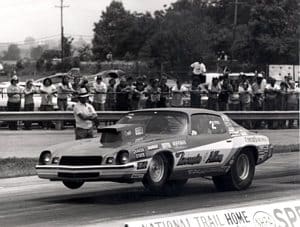

Pro Stock, in those days, brought out the innovator in everyone. Probably the one Pro Stock competitor who would forever change the look of the class was Bill “Grumpy” Jenkins. After receiving approval from the NHRA to run his tube-chassied Vega, he changed the way people approached the class. Remember, the key was to get the lightest car out there with the smallest motor to take advantage of the weight breaks.

When Jenkins won Pomona in his 1972 debut of the Chevrolet compact, it sparked a revolution that led to the introduction of similar small cars such as the Ford Pinto, and AMC Gremlin. Some might argue that the Dodge Colt should be included in that group, but our research showed that while the Hemi Colts made their appearance on the scene in 1973, they were relegated to the sportsman ranks. The Colts were finally legalized for NHRA competition much later.

With the short-wheelbase cars taking over the Mopars were forced to do battle in what seemed to be behemoth Dusters and Demons. The NHRA came to the rescue of the longer-wheelbase cars and offered a weight break, but as a result they stymied the efforts of manufacturers who were trying to market the current body styles. Sure, the Mopar racers stood a chance now, but the guys like Glidden and Nicholson that did battle with the small pony cars returned to their trusty thoroghbred 1970 Mustangs.

According to an article written by Danny White on Bill Pratt’s www.draglist.com, “In 1975, the powers to be at NHRA had weight breaks for every different type of combination, it seemed. The weight breaks were for small car/small block engine, big car/big block engine, small car/big block engine, and big car/small block engine. The different car companies all had different weight breaks for their engines to make it even more confusing. The rules at the start of 1975 had been taking away from the Pinto/Cleveland engine combination with a 6.90 pounds per cubic inch requirement but longer wheelbase cars could run at 6.45 pounds per cubic inch. The cars made at that time by Ford really did not fit into the category of sporty cars that might be considered racecars.”

That led the resourceful team of Gapp & Roush to defend their World Championship in the most unlikely of all combinations – a four-door Maverick. Interestingly enough, this chassis/body style allowed them to run 100-pounds lighter than with their championship-winning Pinto.

It wasn’t long before the NHRA rescinded the age rule that once permitted the brief return to yesteryear. According to White, “Somewhere around the same time, the year rule, which had been four years from last year of manufacture, was waived. The disappearance of this rule, the reason why I have not been able to find, led to some of the neatest cars ever built for Pro Stock. The Fords built using the new rules had weight breaks in mind and soon disappeared after the ruled were changed. Some of the racers who built 1970 Mustangs were Don Nicholson, Bob Glidden, and the Marriott Brothers. Dyno Don Nicholson had Don Hardy of Floydada, Texas, build his 1970 Mustang using the 366 Cleveland Ford for power.

“The car was raced only a couple of times, running a known best of 8.93 at 145 mph. Don had the car rebuilt into a Mustang II not long after the Winternationals in Pomona. Bob Glidden also had his 1970 Mustang built by Don Hardy and the 366 Cleveland Ford built by himself. Bob ‘s car was sleek and very trick using all the tricks of the day. The car was built high in the back and real low in the front. Bob was more successful with his “old” new car than Nicholson running an 8.76 at 154.63 mph. Bob quickly sold his car after the weight break was taken away. Bob was going through cars very quickly during this time, using a couple of Pintos, a Mustang II, a Chevy Monza, and the 1970 Mustang.”

Don’t think for a moment that because of the handicapping and Glidden’s success that this class was boring to watch. Probably the greatest Pro Stock points battle to ever take place under the NHRA banner, occurred during this era when Glidden had to fight tooth and nail to fend off the furious charge of Texans David Reher and Buddy Morrison with their hired driver, the late Lee Shepherd.

Shepherd used a holeshot during the 1980 Gatornationals to beat Glidden, who ran an identical 8.51. Prior to that event, Glidden was entering the new decade, hot off of one of his greatest seasons ever. The longtime Ford stalwart, had qualified on the pole for 15 consecutive events and even more impressive had been in the finals of every Pro Stock race since the 1977 Summernationals in Englishtown, N.J.

Shepherd had only reached the Pro Stock finals in two outings. Both of his final round appearances came at the Cajun Nationals, once in 1979 and in the year prior. In both instances, Glidden emerged victorious. Shepherd entered the 1980 season with little, if any chance, of dethroning Glidden. At this point, it didn’t look as if anyone could, to be honest. However, extensive amounts of testing had the RMS team ready for the giant.

Entering the final event of the season, Shepherd had scored six wins to Glidden’s two. It appeared as if a Chevrolet was going to hold the title for the first time since Larry Lombardo had pulled off the feat in Grumpy’s Monza back in 1977. To catch Shepherd early in the season seemed like a futile attempt when one considers Glidden entered Englishtown nearly 3000 points behind.

The scenario was simple. Shepherd had to qualify and go at least two rounds and he would be the champion. Glidden, on the other hand had to hope for an early exit for Shepherd and establish low elapsed time and top speed as well as win the event.

The final event was at the now defunct Ontario Motor Speedway, the site of the 1980 NHRA World Finals. While the majority of the field was mired in the 8.50s and 8.60s, Shepherd let the Pro Stock contingent know that he was ready to be champion by scoring the pole position with an 8.43, 159.57. Glidden was not giving up either as he landed second with an 8.46.

Both drivers won their first round matches and all Shepherd had to do was win the second round. That’s when the irony struck. The same illness that struck Glidden’s Arrow at Pomona back in February nailed Shepherd’s Camaro when it counted the most. A broken Lenco in the quarters against Andy Mannarino opened the door wide open for Glidden. Glidden set the low elapsed time and the top speed and absolutely gouged out Iaconio’s eyes on the starting line in the final round to score the victory and the championship in one fell swoop.

RELATED STORY – THE MOTHERLOAD OF 1970s DRAG RACING VIDEOS – We have dipped deep into our drag racing archives to provide you with a taste of Drag Racing Heaven. Crank up the speakers, sit back and enjoy the good ‘ol days of this classic presentation of drag racing from the 1970s.