by Jon Asher; Photos by Mike Sopko

Originally published June 2015

Welcoming Race Tracks, Important Aftermarket Manufacturers and Enthusiastic Fans Once Made Chicago A Match Racing Paradise

Once upon a time there were facilities a third the quality and size of stunning Route 66 Raceway in Joliet that were slam-packed with race fans who couldn’t get enough straight-line action. It was roughly the 10-year period from the early 60s through the early 70s, and the place was “Chicagoland,” an area that roughly encompassed not only the Windy City itself, but the surrounding environs. From northern Indiana on the south, all the way to Cordova in the distant southwest, to Rockford directly west on I-90, and even into Wisconsin north of the city, this was the region that locals knew as Chicagoland.

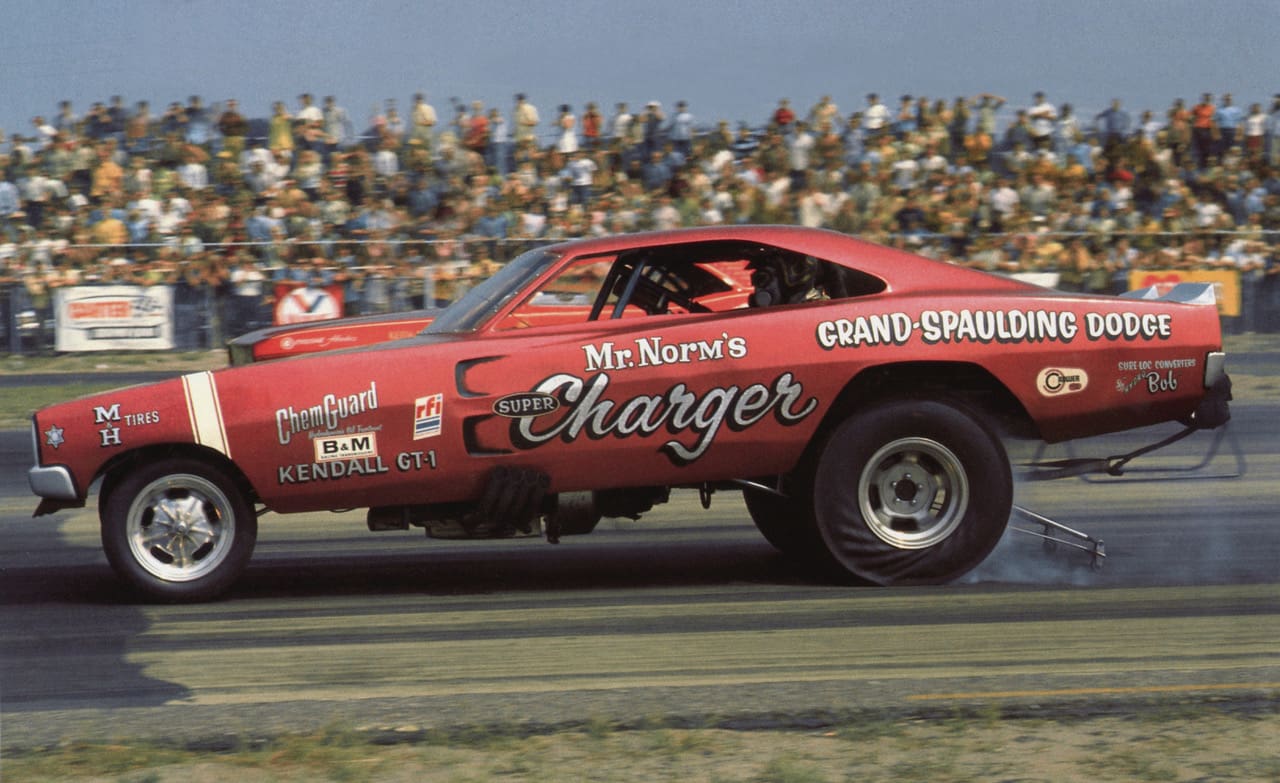

When nitro was in the tank, they had to be Funny Cars. Funny Cars in Chicago were as beloved as the Cubs, White Sox and Bears (the Chicago Bulls hadn’t been “invented” yet!). Old timers – and some not so old — remember those days. They remember a day when the phrase “Sunday, Sunday” blasted out of 50,000 watt radio station WLS, which could be heard from St. Louis to Kalamazoo on a clear evening. It was the battle cry announcing the arrival of more nitro-burning floppers coming to town. It meant anyone – and everyone – from the Coca-Cola Cavalcade of Funny Car Stars, to the likes of a heads-up, knock down, drag out two-out-of-three between Mr. Norm’s Grand-Spaulding Dodge and Arnie “The Farmer” Beswick.

What were those match races like? For one appearance at Oswego between the Grand-Spaulding car and Beswick, Norm Krause, the flamboyant owner of the Windy City dealership, hired a small plane to bomb the track with leaflets. On one side they read, “Go Go Dodge, Beat That Factory-Backed GTO,” and the other were listed “10 Reasons The Dodge Will Win” or it might have been “10 Reasons The Pontiac Will Lose,” I can’t remember which. Never mind the fact that it was Krause’s Dodge that actually had the factory backing, while Beswick toiled on his own – but maybe he did have some support from Detroit. Who knows?

If Southern California was considered the Mecca of Top Fuel dragsters, then Chicagoland was Heaven for the Funny Cars. If your drag racing vehicle flipped the top, and you were serious about your drag racing, you were most likely spending a considerable amount of time within a 200 mile radius of Chicago.

So, what made Chicago so special for Funny Cars? Simply put, if you wanted one built, you went to, or relatively close to, Chicago. If you wanted to race your Funny Car four nights a week, you went to Chicago. If you wanted to get paid, you went to Chicago. This is not to suggest, of course, that there weren’t other places to get a car built, or other places to race, but most of them paled in comparison to Chicagoland.

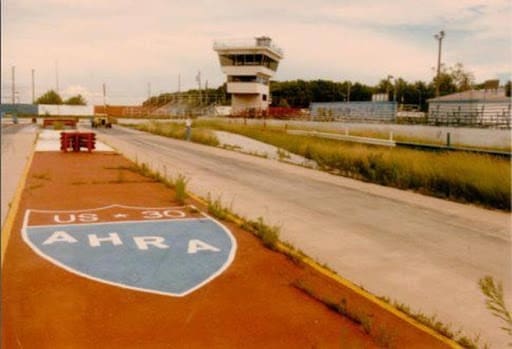

There were four major drag strips in the Chicagoland area, “major” being a relative term. On any given weekend, there were booked-in shows at “beautiful” U.S. 30 Dragstrip(Gary, Ind.), Oswego Drag Raceway (Oswego, Ill.), Rockford Dragway (Byron, Ill.) and Union Grove Raceway (Union Grove, WI.). Other drag strips came and went out of business during the late 60s and 70s in the same region, all of them having had their share of booked-in shows, shows that might have included the superstars, or maybe the injected Funny Cars of the Midwest UDRA Circuit.

Those screaming “Sunday, Sunday” radio commercials touted tracks from U.S. 30 to New York National Speedway in Center Moriches, Long Island, and were largely produced by the Gold Agency in Chicago. They were the ones that tagged God-awful U.S. 30 as “beautiful,” a word no one who ever raced at or visited the place ever used to describe it. Since the stations running the ads couldn’t usually be heard in other markets, if you traveled you’d hear the same basic ad for U.S. 30, and three or four hours down the road you’d hear the same basic ad for Detroit Dragway. If you kept heading east, sure enough, there’d be the same one for New York National. Only the names of the participants might be changed, but in an era when drivers ran three or four times a week, you might hear Jungle Jim Liberman being touted in every one of them.

The term “Chicago-style” racing was coined by U.S. 30 from their Wednesday night shows in which any number of paid-in performers would make two runs, with the two quickest returning for a third, deciding race. Of course, since the track had a nationwide reputation for hot clocks, elapsed times and speeds really meant very little. The odds were that unless something truly egregious took place on the track, the two guys with the biggest guarantees were the ones coming back for that third run!

There was no question that it was the center of Funny Car activity in the late 60s and early 70s, and I was fortunate to have had a front row seat for the Chicago Funny Car experience.

One of the industry’s key players at the time was Ron Pelligrini’s Fiberglass Ltd. emporium, located in a Windy City suburb. It was one of only two outlets for Funny Car bodies in the country, so any racer needing repairs or a new shell ultimately ended up coming through town. I spent a lot of time hanging out at Peligrini’s. I was really in a good situation. Once I got to know the drivers, it was no big deal to get them to go to a park somewhere and pull their cars off their ramp trucks to shoot a feature for a magazine. There were a dozen magazines covering drag racing at the time, so it was pretty easy to get stuff published – even my pathetic, out-of-focus photos with telephone poles “growing” out of the roofs of the cars. Those Funny Car articles that my colleagues and I penned only added to the lure of the class, and in particular that region of the country.

It could be argued, by the way, that Pelligrini’s supercharged Mustang was the first blown car in the country, but we are absolutely, positively not going there!

If you needed a chassis you had your choice of Logghe Stamping Company in Michigan, where Jay Howell created magic out of chrome moly. There was also Chicago-based jet car driver Romeo Palamides, who once built cars for Don Schumacher and Beswick that opened from the back, not the front. A littler further north, just over the Wisconsin line, was R&B Race Cars, where Dennis Rolain and partner John Buttera also made magic.

Ensconced in the Chicago suburbs were fledgling businesses like Strange Engineering, which continues to be the sport’s leading supplier of driveline componentry today. Ed Stoffel’s Quartermaster Industries was also on Chicago’s north side, where the two-speed transmission was first perfected. On the south side of town was the massive King Speed Shop operation, which sponsored a veritable fleet of pearl white and candy orange-painted cars. Around the lake in Michigan were unforgettable places like the Ramchargers, Al Bergler’s metal fabrication plant and more – and take our word for it, we’re just scratching the surface here.

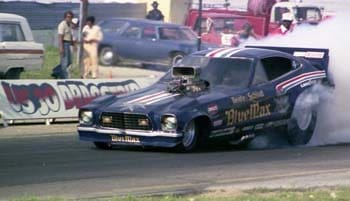

SIDEBAR – U.S. 30 AND THE BETTING GAME – Drag racing and betting can make for some interesting war stories and former Blue Max crew man “Waterbed” Fred Miller remembers very well his experience with two of the key figures in the U.S. 30 betting system.

“There were two African-American guys that were well known around U.S. 30 and let’s say they oversaw the wagering, among other things in the grandstands,” Miller said. “They answered to the names of ‘Dog’ and ‘Rabbit.’”

Once you had your Funny Car and needed to earn the bucks to recoup your investment, you went through the Gold Agency to get match race bookings, but they weren’t the only ones booking cars. Both Ron Colson and Ben Brown also handled bookings, and if this seems like overkill, remember that virtually every track east of the Mississippi River thrived on hired-in shows. There was plenty to go around, with the real rivalries being between the various agents. For example, Richard Tharp has said that during his tenure behind the wheel of the Blue Max he once ran 115 match races in a single season. That meant Friday nights, Saturday nights, Sunday afternoons, Tuesday or Wednesday evenings and starting all over again the following Friday night.

The infamous “Sunday, Sunday” catchphrase became the lynchpin of nearly every drag strip promotion of the era. The ads were horrifyingly crass and scared the heck out of the mothers of America, but they brought the fans out. When they’d start talking about other cars, like “Animal Eliminator,” you knew that everything bad your neighbors thought about you because you were into drag racing was being cemented into their minds.

The tracks these fans piled into were anything but lookers and were merely built just to hold a race, with very few of the perks – make that none — that today’s race fans have become accustomed to. The most popular of the Chicagoland tracks, U.S. 30, was incredibly bad. Ben Christ, the owner, did nothing to maintain it. They had a railroad tie wall at the end of the track to keep out-of-control cars from going into the neighborhood.

Legend has it that one dragster did run off the end of the track and hit the solid wall, launching it into an adjacent yard. When “safety crews” arrived to extract the obviously deceased driver, they were met by the shotgun-toting neighbor, who threatened to shoot anyone who dared step onto his property.

A gun-toting neighbor couldn’t compare with the out-of-control action which transpired inside the confines of U.S. 30. The atmosphere went beyond wild. If something was capable of happening out of the ordinary, it transpired, usually at U.S. 30 or one of the neighboring match race tracks. Gambling was rampant, with winners determined by who got to the finish line first. Redlights, centerline infractions or running off the track meant nothing. The finish line meant everything. Fights, the occasional stabbing and yes, even gunfire could be heard from the grandstands from time to time.

I was ultimately banned from the track for writing about such things. I was incredibly naïve. I thought ownership should actually care about their competitors and fans. How wrong I was. Christ once told me, when I asked him why he didn’t fix the place up a little, that all he cared about was having everyone within the listening voice of WLS Radio come out to his track, just once. He didn’t care if they ever came back, and when I told him that when people went home from that first visit and told their friends what a hole it was they’d never come out, his answer was, “Ah, they won’t believe ‘em!” He must have been right, because I remember hearing he retired to a condo in Hawaii a very rich man.

Chicago might have attracted a fair amount of visiting flopper teams but it also had a huge stable of homegrown talent. The first to bring notoriety to the area was arguably Gary Dyer in the Mr. Norm’s Grand-Spaulding Dodge supercharged altered wheelbase ’65 Coronet. He was soon followed by the likes of the Sedlak Plymouth, another supercharged altered wheelbase car that morphed into the never-to-be-forgotten Farkonas, Coil & Minick “Chi-Town Hustler.” Add to the mix other famous match racers like Arnie “The Farmer” Beswick, Gordon Gilkison’s “Viking” blown Chevy II, Cliff Brown’s “Chicago Kid” Mustang, the all-steel blown Chevy II powered by a 392 Hemi of the Creasy Bros., brother Dean and driver Dale (Senior, not Junior!), the Mercury Comet of Midwest UDRA president Ed Rachanski the Chapman speed-shop-backed Camaro driven by Ron “Snag” ODonnell and literally more than I can possibly remember.

Oh yeah. And then there was this young guy with a nice looking Dodge Charger called “Stardust” named Don Schumacher, who, incidentally, had his initial “race shop” in the back corner of Pelligrini’s Fiberglass Ltd. shop, which was pretty darn small in its own right.

“The events were wild,” Schumacher says. “Chicago was probably Number One in terms of having a totally different atmosphere.

“The fans were so involved in what lane won, and it didn’t matter if you red-lit or not. They didn’t care and that didn’t matter. It was all about who got to the finish line first. There were thousands and thousands of dollars bet on every run. They wouldn’t think a thing of coming down to your pits and letting you know about it.”

“Waterbed” Fred Miller, a longtime Blue Max crew man, did his share of U.S. 30 racing, and remembers how serious the players in the betting system were.

“One marquee race driver, and I won’t call any names, had a provision in his contract that if he won the first two, he didn’t have to run the third one,” Miller said. “He did that one night, pulled up there and said the rear-end broke – when he towed back to the pits and loaded the car into the trailer, two of the key guys in the betting demanded to see the broken car. Security had to be called in at that point.”

“Security” at U.S. 30 more likely than not meant a couple of guys openly packing hardware, not uniforms!

Top Fuel dragsters never really had a chance in Chicago and that can be attributed largely to location and attitude, I believe. I think the main reason is that the dragster guys were separated from most of the fans and racers because they needed long push starts. They were always at the other end of the drag strip and weren’t near the real pits and spectators. They would come out at the quarter-mile, push down the strip, turn around to race, and then go directly back to their hinterlands pits. They were segregated from the fans. Many of them developed an anti-fan attitude in the sense, “We’re racers, we’re cool, we’re here to race, so don’t bother us.”